|

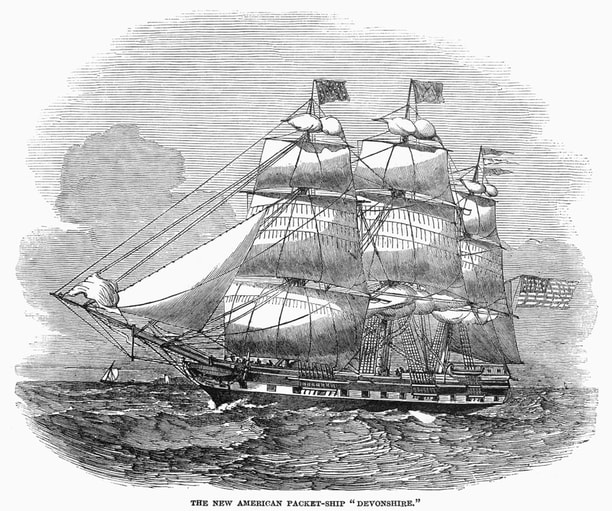

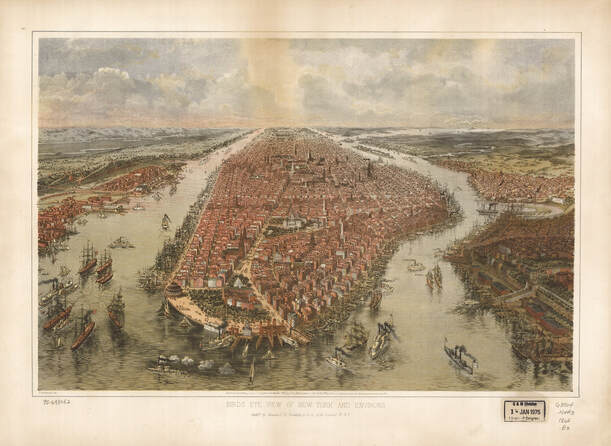

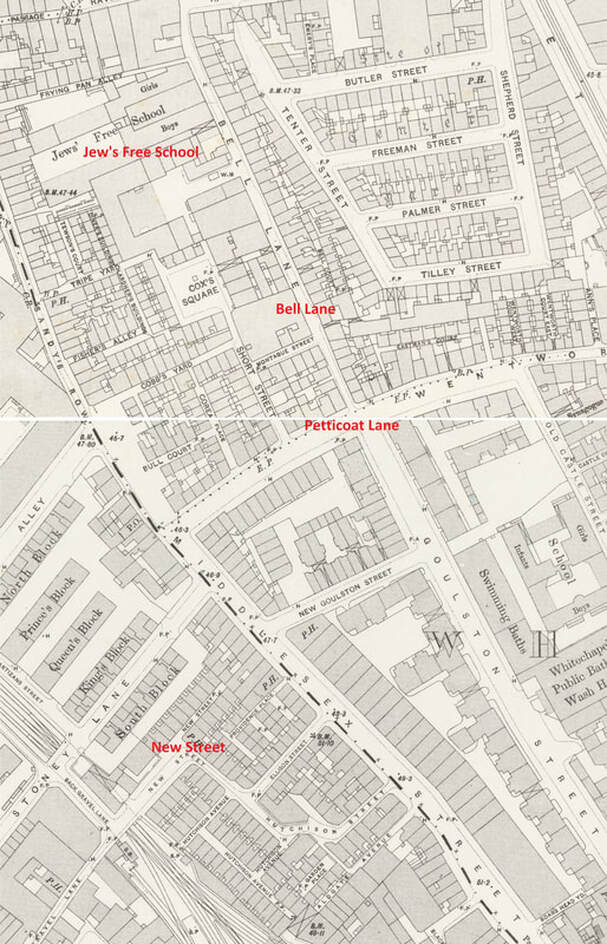

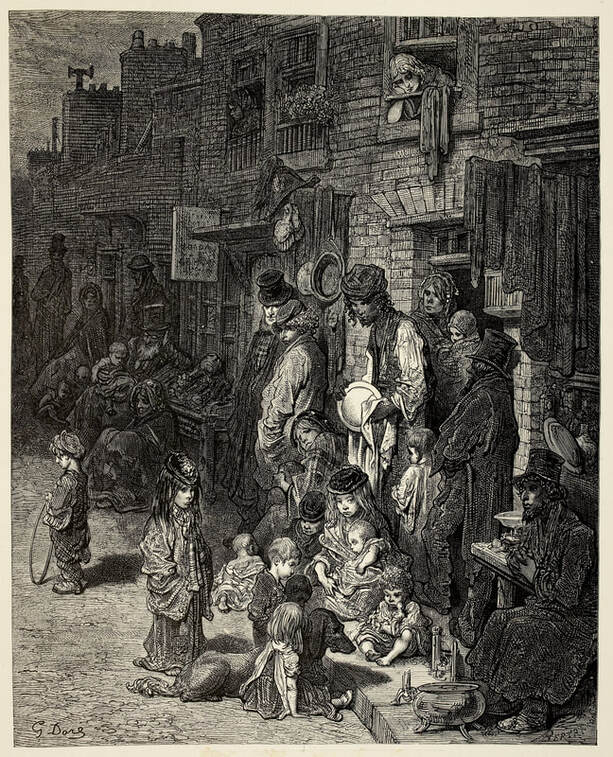

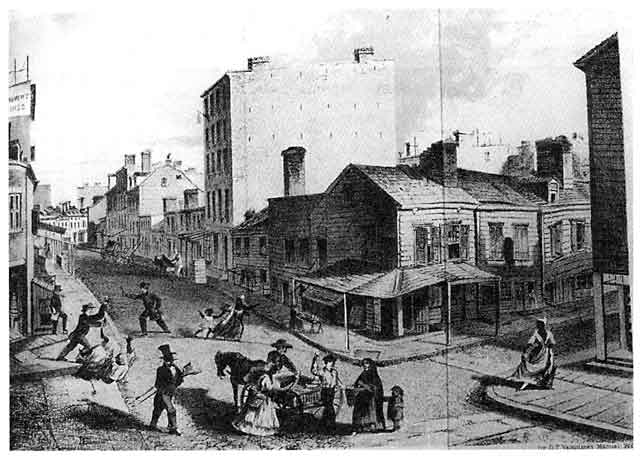

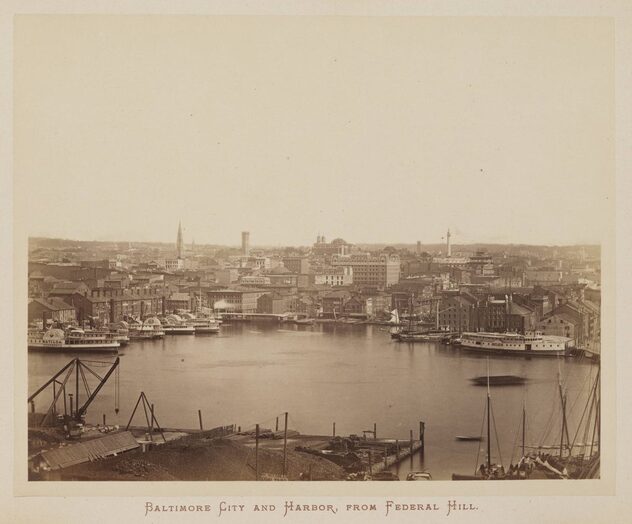

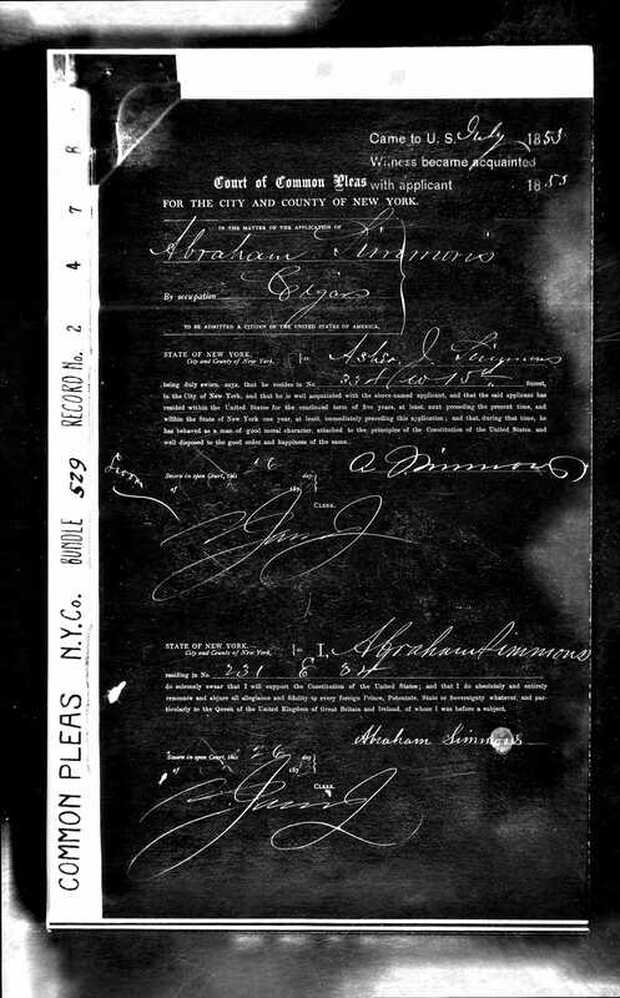

My wife's 3x great-grandfather, Abraham Simmons, must have been tremendously relieved as he stepped off the overcrowded ship onto the pier in New York City. The 400-foot-long, three-masted packet ship Devonshire had carried 581 German and British men, women, and children across the Atlantic Ocean from Liverpool, England. On this July 7, 1853, there had been no Statue of Liberty to sail past, and no Ellis Island or Castle Garden to screen the new wave of immigrants. Nineteen-year-old Abraham merely declared himself before a Custom's Officer and then strode into the Lower East Side, widely known as Little Germany. New York was in the midst of a decades-long population explosion; it would almost double in size over the next ten years, from six-hundred-thousand to over a million, driven mostly by Irish immigration. However, Abraham would not have been too intimidated by the sprawling city before him; he had grown up in one of the toughest neighbourhoods of the largest city in the world: the district of Whitechapel in London, England. He also would not have been entirely alone in his new city. Asher Simmons had earlier arrived in New York in 1845, also from Whitechapel, also nineteen, also settling in the Lower East Side, where he found work as a furrier. A year later, he married Abigail Jones, who had lived near him in London, and a year after that, they had their first son, Morris, followed by a daughter, Sarah, in 1849. Asher's younger brother, Benjamin, a cigar maker, immigrated to America in 1848 and lived with Asher and Abbie for a few years before he moved to a boarding house. Back in Whitechapel, Asher and Benjamin had lived on Little Middlesex Street and then New Street, only a few short blocks from where Abraham grew up at #9 Bell Lane. Abraham was the eighth of ten children born to Levy Simmons and Sarah Cohen, who had married May 24, 1818, at the Great Synagogue on Duke Street. Asher had been the first of ten children born to Joshua Simmons and Sarah Collins, who had married at the same Ashkenazi synagogue on September 4, 1822. Both of their fathers, Levy and Joshua, had been "general dealers," street sellers who peddled a variety of used-clothing and second-hand wares. They may have plied their trade in the Petticoat Lane Market, along Wentworth Street, around the corner from Bell Lane. Visitors to the market would have heard the sing-song cries of "old clo'!" from used-clothing peddlers. At the same time, other dealers would have pressed them with a wide variety of goods, such as fruit, sponges, combs, pocket-books, pencils, sealing wax, paper, pen-knives, razors, pocket-mirrors, shaving-boxes, old books, and glassware. Some dealers even hawked discarded cigar butts, scavenged from the gutters by industrious urchins. Sadly, Abraham's father, Levy, died some time previous to 1851, and his wife, Sarah, took up his trade. The families of Abraham and Asher undoubtedly knew each other; they may have even been relatives. In 1853, New York was home to a thriving Jewish population of twenty-thousand, over twice the size of the London Jewish community. Most of the New York Jewry had recently immigrated from Germany, and by the end of the decade, their numbers would double to forty-thousand. However, while Asher, Benjamin, and Abraham were Jewish, they were also English, and they instead found lodgings in predominately English and Irish immigrant neighbourhoods. In 1855, Abraham shared a single room with Louis Lazarus, who had lived near him in Whitechapel, in a six-room brick building. Abraham apprenticed as a cigar maker in London, but now he and Louis served as clerks, for which they were likely well qualified. Most of the poor Jewish children in the Whitechapel District attended the Jew's Free School, located on Bell Lane, financed by private philanthropy, much of it from the wealthy Rothchild family, who purchased the children's new clothes every year. The Jew's Free School enrolled 600 boys and 300 girls, segregated into separate wings. While all students learned to read and write in English and Hebrew, the boys focused on trades, while the girls learned needlework and laundering. Abraham appears to have acquired the craft of cigar making. Consequently, Abraham very likely found work as a cigar maker in New York at some point. Hand rolling a cigar was a skilled trade, especially without the tools that would come later, and the manufacturies in New York were still very basic. Abraham would have sat at a table in a tenement apartment with several other men, rolling cured, fermented tobacco leaves into cigars. Even if he had started as a cigar roller, he may later found other jobs, inspecting leaves or selling cigars from a street cart, which was where most new merchants got their start. Everything changed on October 7, 1857, when the bark Quickstep tied up at the immigrant landing deport at Castle Garden on the southern tip of Manhattan, the precursor to Ellis Island. Among the 134 English, Scottish, Irish and German passengers were the family of Asher and Benjamin: 52-year-old Sarah Simmons and six of her children: Rosetta, Rachael, Rebecca, Sarah, Louis, and Agnes. Unhappily, their father, Joshua Simmons, had not made the journey; he had died of heart disease at the age of 61, at about a quarter past eleven on April 20, 1857, in the back apartment of a surgeon on Euston Square in London. Abraham and Rachael may have begun their courtship very shortly after her arrival, as they registered their marriage with the City of New York less than ten months later, on July 28, 1858. Rachael gave birth to their first child, Sarah, on March 15, 1859, less than eight months after they registered their marriage. They would call her Sadie. Three months later, on June 25, 1859, Aaron Simmons, Abraham's youngest sibling, nineteen-years-old, and also a cigar maker, walked through Castle Garden into New York. Whether Aaron's arrival inspired grand plans or the family merely tired of New York, they packed up and moved to Baltimore very soon afterwards. By 1860, Abraham and Aaron, both cigar makers, lived in the 4th Ward of Baltimore, a very ethnically diverse, working-class region of the city, populated by Germans, Jews, Poles, Irish, and African Americans, who worked as shopkeepers, cigar makers, bricklayers, shoemakers, and machinists. At this time, Baltimore suffered an upsurge of nativist sentiment with many anti-immigrant "clubs," such as the Plug Uglies, Rip Raps, American Rattlers, and Blood Tubs. These clubs were frequently involved in parades and torch-lit processions that marched through many different neighbourhoods, often sparking clashes with residents that devolved into violent brawls and riots, where many of the participants armed themselves with picks, axes, and even muskets. These clubs attempted to keep control of the city government through acts of violence and voter suppression. As an alien and not entitled to vote, the federal election of 1860 might not have greatly interested Abraham or Rachael, but the escalating rhetoric certainly would have had their attention. The newspapers darkly warned of secession and war should the country elect Abraham Lincoln. The election occurred in Maryland on November 6, 1860, and Lincoln received almost no support in Baltimore, which divided between John Breckinridge and John Bell, both of whom would support the Confederacy during the Civil War. However, Lincoln did win the national election and, as the southern states exited the Union one after another, many in Maryland organized to have their state also secede. A week after the Confederate Army captured Fort Sumter, anti-war protesters and Confederate sympathizers blocked the transport of Union militia through the city by tearing up the railroad tracks. The Union volunteers from Pennsylvania departed the train and marched along Pratt Street toward the next station, their route passing within three blocks of the Simmons home at 72 North Eden Street. However, a destructive mob descended on the column, assaulting them with bricks and musket fire. The soldiers returned fire and the scene devolved into an uncontrolled melee, which left four soldiers and twelve civilians dead. The Baltimore Jewish community was as divided about the conflict as the rest of the country. Orthodox Rabbi Dr. Bernard Illowy defended the right of the South to own slaves and to secede from the Union. Reform Rabbi Dr. David Einhorn unwaveringly condemned slavery and was run out of the city by an angry mob. Rabbi Dr. Benjamin Szold and Rabbi Henry Hochheimer were more circumspect. They called on their congregations to pray for the Union and to assist victims of the war, but otherwise, they remained conspicuously mute on the more contentious issues. Most of the Jewish community in Baltimore followed suit. Over the next several months, the United States declared martial law in Maryland, arresting hundreds of politicians, judges, and citizens who expressed southern sympathies, criticized Lincoln, or inconveniently asserted their rights in defiance of martial law. None of this appears to have directly impacted Abraham Simmons, however, as he continued to run his business. Now forty-years-old, Abraham enrolled in the draft in 1863 but obtained an exemption since he was not an American citizen. He had a few minor problems. Two young boys stole some money and tobacco from him in 1863, but police caught and charged them. In 1864, Abraham was arrested and fined five dollars for selling cigars on a Sunday. By the end of the war, the Simmons family had moved to a new house at 65 South Sharp Street in the 10th Ward, and then they moved around the corner to 74 South Howard Street. They likely needed a more substantial residence as their family grew. They had Rosetta in 1861, Jane in 1863, Agnes in 1865, Louis in 1867, Amelia in 1869, Joshua in 1873, and Lillian in 1875. Abraham and Rachael owned several hundred dollars in inventory, but they were not so successful that the children didn't need to work. The children went to school until they were about twelve when they then learned a trade. Sadie became a dressmaker, and her sisters, Rosetta, Jane, and Agnes, found work as hatmakers. When the children grew older, Rachel joined her husband in the business, and they eventually became successful enough to hire additional cigarmakers. Then sometime shortly before 1880, the family moved back to New York, to 608 3rd Avenue in the middle-class Murry Hill neighbourhood of Manhattan. This part of the city was then "uptown," only a few blocks from the wealthy Park and Madison Avenues. The makeup of their new neighbourhood was mostly German Jewish and Irish, and primarily working people, such as carpenters, masons, clerks, silk weavers, sailors and shop keepers but also gentlemen, missionaries, music teachers, and realtors. They had moved a step up in the world. Over the next fifteen years, the family moved several times, first in Murray Hill and then up to the neighbourhood of Lenox Hill, in the Upper East Side. The Simmons family was not untypical in this move; many immigrants, including the sizeable German Jewish population, moved here out of the Lower East Side as they grew more prosperous. However, the Lower East Side would soon become more crowded than ever. The Jewish population in New York had lept from twelve thousand in 1848 to sixty thousand in 1880 or eighty-five thousand counting Brooklyn, and from fifty thousand to two hundred thirty thousand in the entire United States. However, beginning in 1881, years of violent pogroms and increasingly restrictive anti-Jewish laws in Russia provoked a tsunami of emigration from eastern Europe. By 1914, almost three million Jewish people lived in the United States, nearly half of whom lived in New York City, mainly in the Lower East Side. These newcomers did not readily assimilate with the existing Jewish community, which had predominately immigrated from German-speaking nations. Jewish worship in New York and the United States had changed considerably from the forms in much of Europe. In many synagogues, Jewish ministers delivered sermons, some in English, and families sat together, rather than segregating by sex. Increasing numbers of Jewish families did not observe the Sabbath, a trend shared by many German immigrant groups. However, while forms of religious observance divided the community, Jewish cultural, charitable, and secular organizations flourished, creating a new shared identity. Although not German, Abraham and Rachael likely shared far more in common with that more assimilated Jewish community, rather than with the Orthodox, Eastern European immigrants. Cigarmaking in New York had changed as well. Confined to tenement buildings and faced with falling wages, cigarmakers had organized into unions and held mass meetings and strikes. While governments passed laws to outlaw tenement labour, courts invalidated those laws as unconstitutional. However, the unions strongly pressured employers, who eventually moved production into large factories, provided more fair wages, and limited work to eight hours per day. At this point, Abraham was probably more of a cigar dealer than a manufacturer, but the conflict would have affected him. The cigarmakers union placed blue labels on the boxes of cigars produced in the large factories, and he would have likely had to choose sides. On October 26, 1882, Abraham finally naturalized as a United States citizen in the Court of Common Pleas, with his brother-in-law, Asher Simmons, as the witness. American law granted a wife the same status as her husband, so Rachael also became a citizen, although she would never have the right to vote. Abraham would live to see four of his children married. At twenty-six, Rosetta married Isador Meyer on October 2, 1897, and they had three children together. Jennie married Max Aaron on October 9, 1892, at the age of twenty-nine, and they had one son. On October 16, 1898, Louis married Annie Weisberg, and they had no children. His daughter, Sadie, led a more unconventional romantic life. Beginning in 1885, Sadie pursued a seven-year romantic relationship with Isaac "Ike" Silverblatt, the son of a Harlem pawnbroker. Ike had a spendthrift lifestyle and borrowed small sums routinely from Sadie. Sadie broke off their engagement in January of 1892 when she read in the newspaper that Ike had become engaged to Jennie Newman, who lived only a few blocks away from Sadie. Sadie moved on, however, becoming pregnant early in 1893, and left for Philadelphia, possibly with the encouragement of her parents. In Philadelphia, she met Moss Aarons, who had immigrated there from Whitechapel in 1889. The couple travelled to New York and married on June 29, 1894. However, Sadie then left her husband and ran away with Isidor Teschner, a married man who had stood as a witness at her wedding, and they soon had two children together. At this point, she possibly became estranged from her family. Abraham and Rachel would see a lot of change throughout these years. Not only did New York City continue to grow tremendously, but the city constructed famous landmarks, such as the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 and the Statue of Liberty in 1886. Abraham died of a stroke on March 2, 1899, at the age of about sixty-four. His family buried him three days later in the predominantly Jewish burial ground of Washington Cemetary, Brooklyn. His twenty-seven-year-old son, Joshua, died a little over seven months later. At the turn of the century, Rachael lived with her remaining unmarried children, Agnes, Amelia, and Lillian, who worked as a saleslady, a teacher, and a cashier. In 1901, Amelia married Joseph Arrison, and Lillian married Jacob Klausner. Lillian and Jacob would have two children together. Rachael lived with Agnes until her death on January 11, 1913, about the age of seventy-eight. Agnes would marry Edwin Rosenfield the following year. Over almost forty-two years of marriage, Abraham and Rachael had eight children and at least eleven grand-children, while running a successful cigar business. Today, their descendants live in New York, California, Nevada, Colorado, Washington, England, Alberta, and British Columbia. BibliographyJohnson, P. (2013). History of the Jews. London: Phoenix.

New York University Press. (2020). Jewish New York: the remarkable story of a city and a people. Goldstein, Eric & Weiner, Deborah, On Middle Ground: A History of the Jews of Baltimore (2020), John Hopkins University Press https://www.ancestry.com/ https://www.familysearch.org/ www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/ https://www.newspapers.com/ |

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed