|

I've recently been reading a biography of Andrew Jackson, the 7th President of the United States and the founder of the modern Democratic Party. While many historians place Jackson in their list of the top 10 presidents, I personally believe that he was a horrible president with an ugly legacy. However, what did our ancestors of the time think of their president?

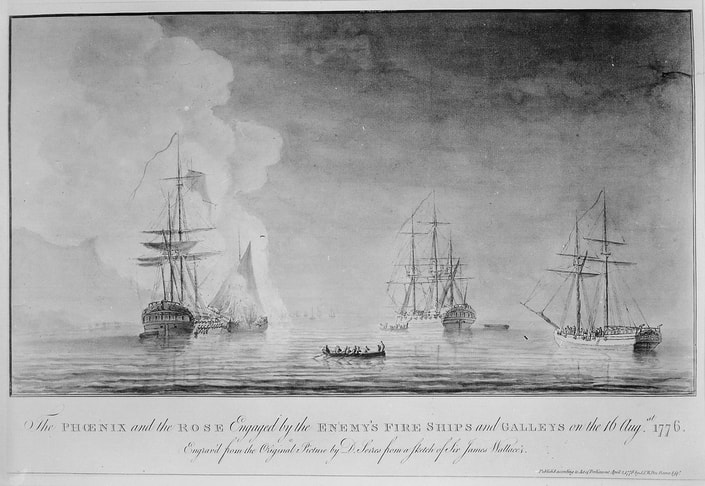

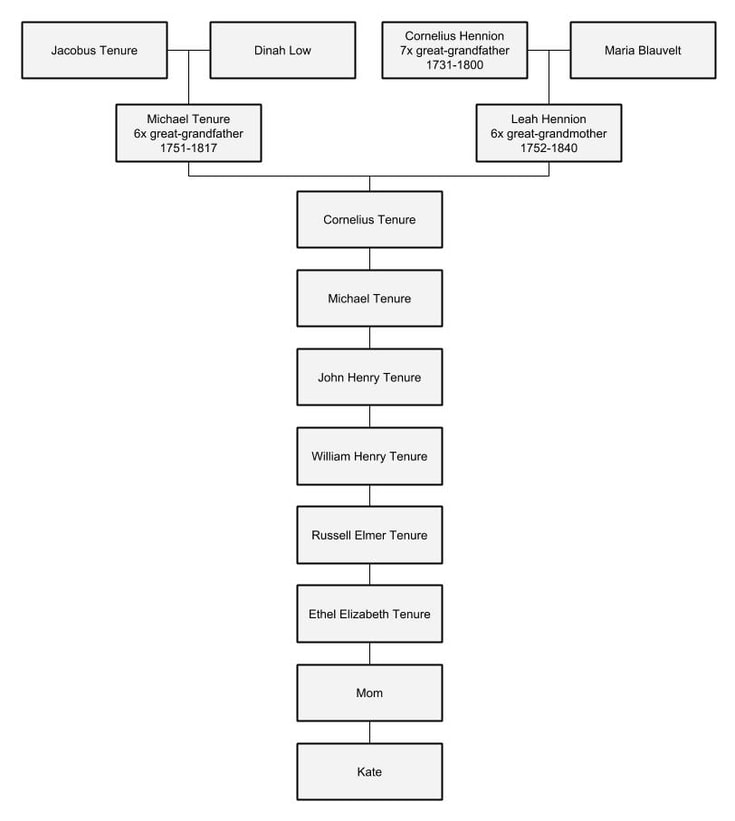

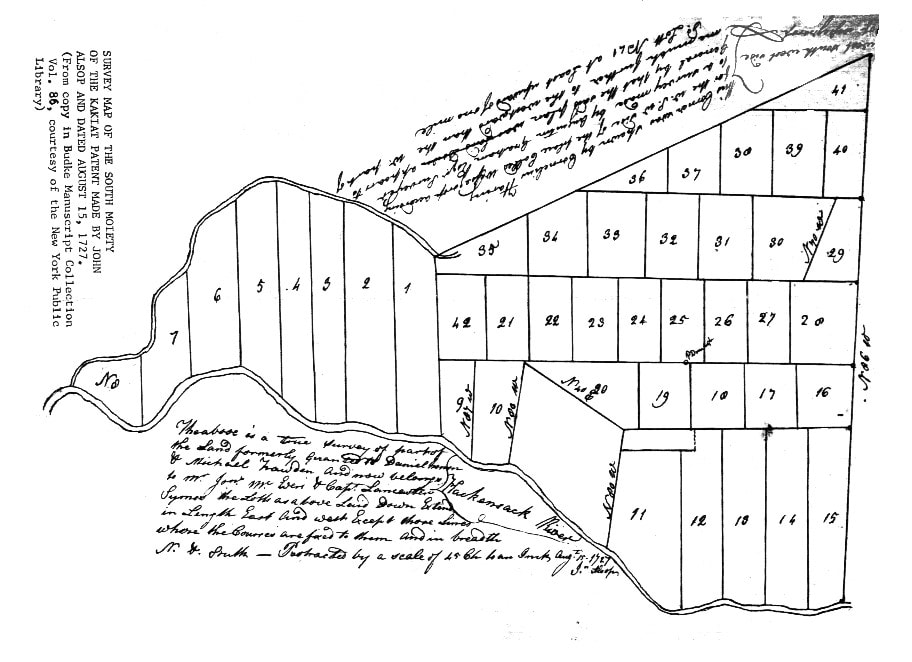

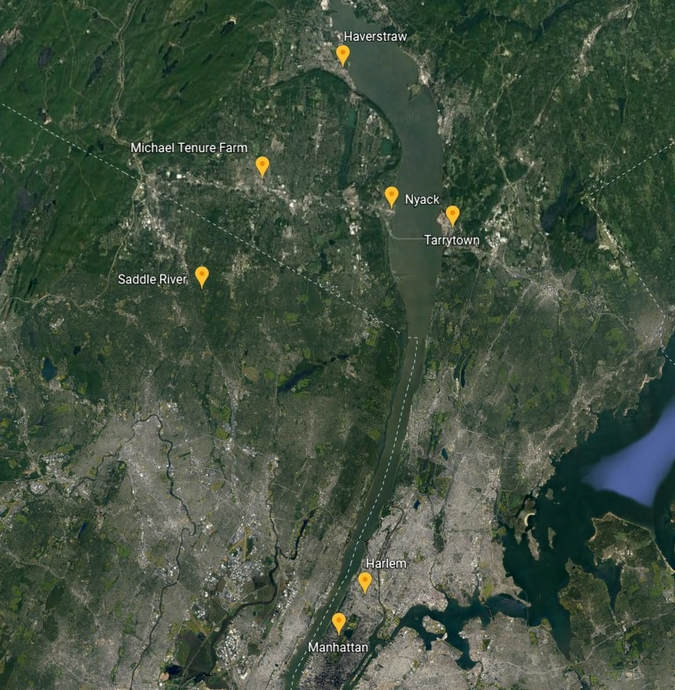

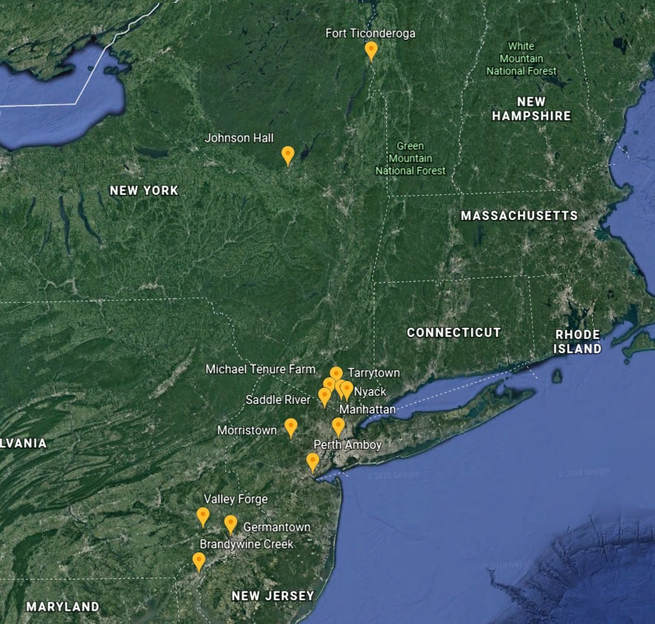

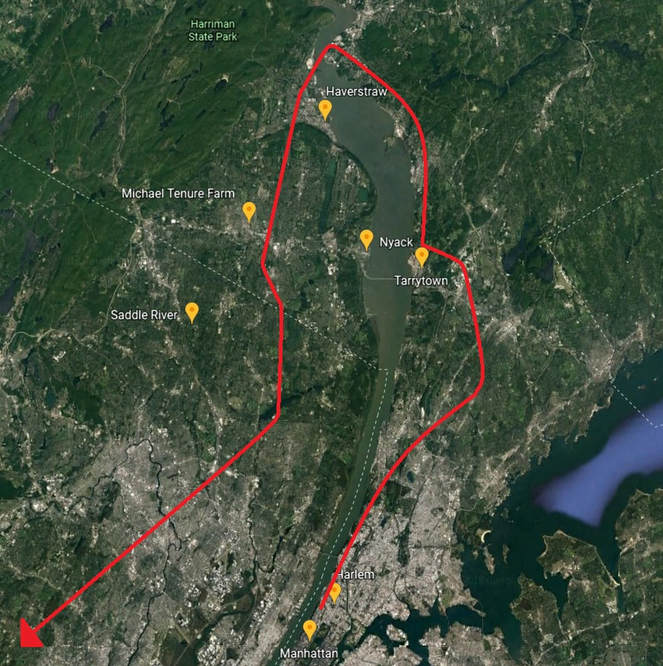

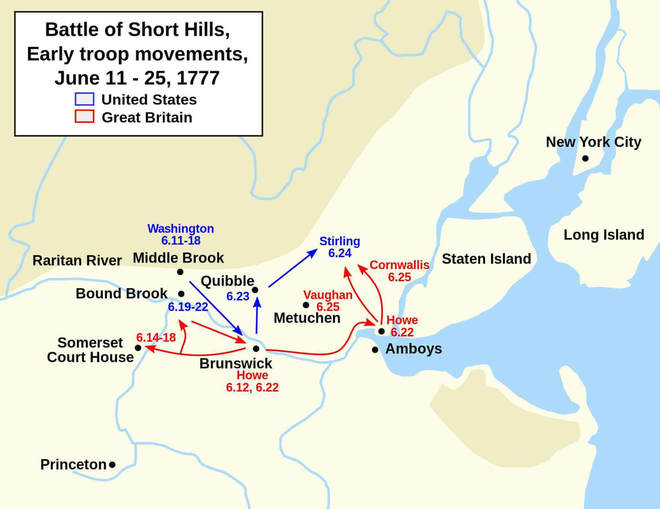

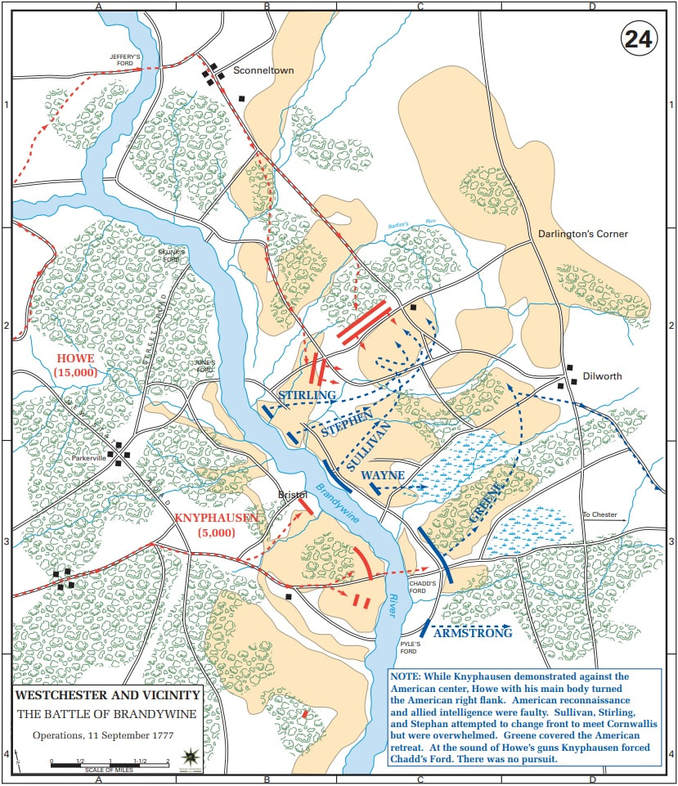

In 1834, after years of political maneuvering between Jackson and the Whigs, led by Henry Clay, Jackson managed to kill the 2nd Bank of the United States by withdrawing all U.S. government deposits and then vetoing the renewal of the bank's national charter. These acts, which many cheered as a blow against the evil eastern bankers, had a predictably calamitous effect on the United States economy. which led to a full blown panic and economic collapse only a few years later. During its fight for survival, as the federal government withdrew funds, the 2nd Bank of the United States tightened credit. This was partly done as a tactic of the bank, to cause hardship which they hoped would be blamed on the president and his party. As Jackson moved federal deposits to undisciplined, barely regulated state banks, tightened credit was replaced by rampant inflation and speculative bubbles, followed by a tremendous crash and 25% unemployment. So what effect did this have on our ancestors and what did they think of Jackson? In 1834, my 3x great-grandfather, Clement Simpson, was a 59 year old farmer in Harrison Township, Pickaway County, Ohio at the time, with his wife, Minty, and 6 of their children, including my 2nd great grandfather, 8 year old Nelson Simpson. During the fight between Jackson and Clay, the many residents of Harrison Township left no doubt to who they supported. They drafted and signed a petition, which they sent to the U.S. Senate, complaining that they face ruin over the collapse of beef, pork and flour prices. They declare that they are free, independent American citizens and as republicans and Whigs determined to "use all lawful means to save ourselves from the iron grasp of our mis-rulers..." They complained that Jackson was guilty of a "falsification of faith" and "an unwarrantable usurpation of executive power". Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 This was a boilerplate testimonial signed by many farmers all over the country, many of whom lost their farms as credit disappeared. Colonel Ann Hawkes Hay sat down at his desk to pen a letter to General George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, which was fortified in the City of New York: The Enimy now lie in Haverstraw Bay and are using every effort to land and distroy the Property of the Inhabitants, the great extent of Shore I have to guard obliges me to keep the greatest part of my Regiment on Duty in order to prevent their Depradations. Colonel Hay then sent a plea for funds to the New York convention: My regiment consists only of three hundred men, and very near one half of them are without arms. I should be very glad to know what I am to do, and where I must apply for a reinforcement in case they should attempt a landing on the the west side of Hudson’s River. It was the summer of 1776, soon after Congress had declared American Independence, and a 26-year-old New York militiaman, Private Michael Tenure, may have been one of those three hundred men patrolling the west bank of the Hudson River, serving under the command of his uncle, Captain Hendrick Tenure. The 44-gun Phoenix and 20-gun Rose, along with 3 tenders, had easily run past the American forts guarding the river and were now anchored in Haverstraw Bay, only a few miles from Michael’s home west of Nyack. Only days earlier, foraging British sailors and marines had attacked the farm of Jacob Halstead, a half-blind farmer, burning his house and barn and stealing his pigs. Over the next few weeks, Patriots launched a series of attacks against the British warships with gunboats and fire ships. The British warships easily fended off the attacks, only losing one tender. Despite the failures, fierce Patriot resistance made it almost impossible for the warships to resupply and eventually they withdrew to join the assault on the City of New York. After the departure of the British warships, Michael shouldered his musket and walked home with his Uncle Hendrick. Michael owned 25 acres of land, inherited the previous year from his paternal grandfather and namesake, which adjoined his uncle’s farm, which adjoined the farm of Michael’s father, Jacobus, which adjoined the land of his double-first cousin, Hendrick Turneur. All of this land originally belonged to Michael’s great-grandfather, Hendrick Oblenis, who had purchased 800 acres in the south moiety of the Kakiat Patent, on lots 11 and 12 above. Soon after his inheritance, Michael proposed to his sweetheart, 24-year-old Leah Hennion, who was from Saddle River in Bergen County, New Jersey, about 6 miles south of Michael Tenure's farm. They married on December 29th, 1775 [1] in the Dutch Reformed Church. When Michael arrived at his house and walked in the door, he was greeting by Leah, 7 months pregnant with their first child, a son whom they would they would name Cornelius, presumably after Leah’s father. Michael and Leah’s families were among the original Dutch and French Huguenot settlers of New Netherland, who had first arrived in North America over a hundred years earlier. Their parents had sold their property in Harlem and settled west of the Hudson River, in Orange County, New York, and Bergen County, New Jersey. They were related to most of their neighbours and many, if not most, primarily spoke Dutch. The Native Americans in the region had been the Tappan, as named by the Dutch, a Lenape people who occupied most of current day Rockland and Bergen Counties. In their early interactions with the Dutch in New Netherland, the Tappan traded furs, planted corn, and migrated seasonally, hunting and trapping. However, after several conflicts with Europeans and under pressure from the Iroquois, the Tappan gradually disappeared from the region, selling their land in large sections and moving west. They sold the Kakiat Patent in 1694, where the Tenures lived at this time. [2] Days after arriving home, as Michael and Leah awaited the birth of their child, they learned where the Phoenix had gone. From the deck of the warship, Admiral Richard Howe coordinated the landing of thousands of British and Hessian soldiers in Brooklyn, routing the Patriot defenders. Admiral Howe’s brother, General William Howe, now commanded a British army in Manhattan, facing the entrenchments of the Continental Army. Several weeks passed. As summer turned to autumn, the Tenures were likely busy bringing in the crops and storing away preserves for winter. As Leah gave birth to Cornelius on Monday, September 30th [3], their thoughts must have been torn between the joy of the moment and worry about the war. Word had reached them that the British had occupied part of New York City, easily overwhelming the disorganized American resistance. Most of the residents of New York had fled the city, many possibly staying with friends and family in Orange County. Cornelius HennionTo compound their worries, Leah’s father was serving with the American army in the wilderness near the Canadian border. Forty-six year-old Cornelius Hennion had joined the New Jersey Line on February 8th, 1776. He had been a widower since the death of his wife, Maria Blauvelt, 6 years earlier, leaving him a single parent to several minor children. Leah was his oldest, so the rest were likely left in the care of family or friends, possibly even Michael and Leah, as Cornelius joined the first company of the third battalion, commanded by Colonel Elias Dayton. Cornelius would have been called upon to swear the following: "I, Cornelius Hennion, have this day inlisted myself as a soldier in the American Continental Army for one year, unless sooner discharged; and do bind myself to conform in all instances to such rules and regulations as are or shall be established for the government of the said army.'” Garbed in grey coats with dark blue facings and cuffs, buckskin breeches, and hats with white bindings, the 3rd New Jersey was nicknamed the “Greys”. After watching the battalion march, Washington dubbed them “the flower of all North American forces”. The New Jersey Brigade was divided between Staten Island, New York and Amboy, New Jersey. However, after only a few weeks, on April 28th, 1776. the companies reassembled at Elizabethtown then marched for New York where, on May 3rd, they embarked onto sloops and sailed up the Hudson River for Albany. Colonel Dayton reported there to Brigadier General John Sullivan, of New Hampshire. During the summer, they were stationed at Johnstown, German Flatts, where they constructed Fort Dayton and skirmished with British-allied, Native American forces in the wilderness. In early June, men from the regiment, led by some officers, ransacked Johnson Hall, the home of Sir John Johnson, the British superintendent of Indian Affairs, who inherited the post from his father, Sir William Johnson. During the attack they “broke open the Tomb of Sir William Johnson, took out and burnt the Body, and threw the ashes in the air.” This proved an embarrassment and risked inflaming the passions of the local Native Americans who had a close attachment to the Johnsons and it may have resulted in some courts-martial because soon after, on July 19th, Cornelius was promoted to 2nd lieutenant. On October 12th, the regiment was sent to Fort Ticonderoga, which was being threatened by a British army from Canada. When they arrived on November 1st, the delaying tactics of American general, Benedict Arnold, had succeed and the British were withdrawing with the onset of winter. During the long, dark winter months garrisoning the redoubts, Cornelius was promoted to 1st lieutenant, on November 29th. March 23, 1777 (Morristown, New York)The battalion left Albany March 7th, 1777, and was honorably discharged at Morristown, New Jersey, on the 23rd of the same month. Meanwhile, the word from New York City was not good. A devastating fire had destroyed much of the city, which many blamed on the retreating Patriot army. Then, on the afternoon of November 12th, the Tenures and their neighbors may have seen George Washington and 2,500 soldiers marching past, having slipped out of New York, marching north to Peekskill and now circling south towards New Jersey. Days later, the British completely overwhelmed the last American resistance in Manhattan, capturing more than 5,000 Patriots. Over the next several months, as the British and American armies skirmished against each other in New Jersey, Michael and Leah faced a grave situation. British and Hessian forces were wintering in New York and horrible stories began to leak out. Barely controlled, soldiers raped and murdered with impunity, often loyalist and patriot alike. Moreover, just across the Hudson, loyalists launched terrifying raids against their patriot neighbors. In response, the New York militia reorganized and Captain Hendrick Tenure divided his men, including Michael, into groups of four. Each week, rain or snow, one of the four in each group would take station along the banks of the Hudson River to warn against any British or loyalist movement on the river. As the brutality of loyalist raids across the Hudson grew, the watchers must truly felt the peril of their stations. Meanwhile, the 3rd New Jersey Regiment, along with Lieutenant Cornelius Hennion reformed. After reenlisting, Hennion had 20 days leave, which he may have used to return to Saddle River and visit with his family and see his first grandchild, 6 month-old Cornelius Tenure, for the first time. After his leave, Cornelius re-joined his battalion with Washington’s army at Morristown, encamped in a fortified and defensible position where they could watch and respond to any movements by General Howe and the British army. June 9, 1777 (Perth Amboy, New Jersey)Howe crossed his army from Staten Island to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and marched his army to Somerset Court House, almost halfway to Philadelphia and the Continental Congress. Howe had hoped that this feint would draw the American army away from their strong position at Morristown but Washington was not fooled. After 5 days, Howe abandoned his ruse and marched his army back to Perth Amboy. Eager to bloody Howe, now Washington did mobilize his army, maneuvering to harass the withdrawing British forces. He appointed one of his generals, Lord Stirling to lead a force of 2,500 men, including the 3rd New Jersey Regiment into a strong forward position. On June 26, with the American Army now exposed, Howe turned and attacked Lord Stirling's command. The Americans fell back into the underbrush, firing on the pursing British, until finding good defensive ground to fight. As the British assaulted the Americans with a clearly superior force, Stirling again ordered a retreat and the Americans fell back again. After a hot day of fighting, the British were too weary to pursue and Washington successfully withdrew his army back to Morristown. Over a 100 Patriot soldiers had been killed in the engagement with 70 captured. The New Jersey Brigade alone had lost 12 men killed, with 20 or 30 wounded, and more captured. From the 2nd New Jersey Regiment, Captain Ephraim Anderson was killed and Captain James Lowry was captured. These unfortunate losses may have created some room for advancement because Cornelius was then promoted to Captain, suggesting he had led his soldiers competently in the battle. He had also been wounded, although the injury must had been minor since he was soon back with his regiment. Having missed his opportunity to bring Washington to battle, Howe and his army returned to New York and enacted his grand strategy. Over 12,000 redcoats boarded over 200 transports and sailed for the Chesapeake, where they would land and begin their march on Philadelphia. Washington would face them at Brandywine Creek. September 11, 1777 (Brandywine Creek, Pennsylvania)At Brandywine Creek, Captain Cornelius Hennion would have fought with his regiment as part of the New Jersey Brigade, under the command of Lord Stirling. Overall, they were part of General Sullivan’s wing, which consisted of 3 divisions of 4,100 men. They were tasked with defending the east bank of the creek while the main American force protected the ford. In the battle, General Howe distracted the bulk of the American army with a huge artillery assault at the center, while sending most of his army over an undefended ford to attack the American army from the flank. On the map above, Cornelius would have fought on the right flank of the American line, falling back to block the encircling British forces, holding back their advance until American reinforcements arrived, then fighting on for hours until darkness fell and his army could slip away. After some more skirmishing, the British Army marched on to occupy Philadelphia. October 4, 1777 (Germantown, Pennsylvania)Washington responded to Howe’s occupation of Philadelphia by attacking the British garrison at Germantown, just north of the city. Captain Cornelius Hennion, under the command of Lord Stirling was in reserve during the attack but was brought forward to assail Clivedon, a mansion belonging to Benjamin Chew, the Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The attacking Americans suffered heavy casualties during their assaults against the manor. Those who manage to enter the mansion were shot or bayoneted and driven back. Cornelius was one of those badly wounded during the assault, a shot hitting him in the elbow. They never succeeded in taking the mansion. In the greater battle, the British rallied and Howe brought up more troops, causing Washington to withdraw. October 4, 1777 (Tarrytown, New York)If Private Michael Tenure was on watch during the first week of October, he would have been alarmed to view 3 British frigates and a large number of smaller vessels sailing up the Hudson, full of redcoat soldiers. A messenger sent to Captain Hendrick Tenure to report the ships may have returned later with news that the fleet had landed the redcoats at Tarrytown, directly across the Hudson from Nyack. This action undoubtedly created deep concern among all the inhabitants of the area, as they feared a British occupation. However, by the next day, the redcoats had re-embarked and sailed further up the Hudson. Michael would later learn that the British, under the orders of British General Clinton, captured two Highland forts on the Hudson, to clear the chain blocking the river to their ships, and then launched an attack on Kingston, the temporary capital of New York, burning every last building to the ground. Fortunately, the New York had government escaped. General Clinton wanted to continue up the Hudson, which likely would have been a disaster for his army, but the battle at Germantown had so alarmed General Howe in Philadelphia that he had sent an order for reinforcements, requiring Clinton to withdraw his forces back to New York City. December 19, 1777 (Valley Forge, Pennsylvania)Following the battle at Germantown and a stand-off with the British at White Marsh, Washington withdrew the Continental Army to Valley Forge, just up the Schuylkill River from Philadelphia, to encamp for the winter. During the encampment, Washington established several field hospitals and ordered his regimental commanders to acquire women to act as nurses. At this time, Cornelius was absent from his regiments because of his wounds and possibly quartered in one of these field hospitals. However, medical supplies were scarce and there was little the surgeons and nurses could do except provide the wounded with a place of rest. Given the severity of his wound, Cornelius would never recover here and on April 1st, 1778, he resigned from his regiment and the Continental Army, and presumably returned home to his home is Saddle River, New Jersey. The War Rages OnCornelius remained on half-pay in Saddle River while he recovered from his wound, although he never did recover the use of his elbow. The rest of the war was a tense affair for the family as the American and British armies sat a few miles apart, with Rockland and Bergen County between them. Patriots and Tories continued to murder and rob each other and on the night of March 23, 1780, a British and Hessian patrol attacked and burned the Bergen County Courthouse, only a dozen miles south of Hennion farm. George Washington was often in the area, even headquartering for a few days in the home of Colonel Ann Hawkes Hay. Benedict Arnold escaped up the river right past where Michael Tenure might have kept watch and the British spymaster, John André, was captured just across the river from the Tenures, outside Tarrytown. EpilogueCornelius had been politically active in the county on a local level before the war and remained politically active after the war, attending the New Jersey Constitutional Convention as a delegate in 1787 and running to be a member of Congress. Cornelius remarried in 1781 and had 2 more sons, Gerrit and David. He died on March 28th, 1800 at the age of 68. Among the various household goods listed in his probate were 50 pounds of flax, 2 cows, 3 hogs, 4 pigs, 13 dunghill fowls and 1 beehive with bees, which indicates that he was a subsistence farmer, much like most people in the region. The 1790 census shows Michael Tenure still living next to his Uncle Hendrick, as well as his cousin, Henry Tenure. His family records himself, a boy under 16, presumably his son, Cornelius Tenure, and 3 females, presumably Leah and possibly 2 daughters. It also shows the family housing 4 slaves, which they may have owned or who may have be hired to the family. Considering the fairly small size of the Tenure farm, slaves certainly were not necessary, On the 1800 U.S. Census, there was no record of any slaves with the family. This again may because the slaves were only hired workers in 1790 or because they had sold or emancipated them. While slavery was an accepted part of the Dutch culture in New Netherland, the Yankee culture of the region was growing more dominant and abolitionist. In 1799, New York passed a law for the gradual emancipation, with a further law and 1804 and an outright constitutional ban on the practice in 1827. Michael and Leah bought a sandstone house and 100-acre farm in nearby Monsey in 1795. The township tax list in 1807 records the family as owning 95 acres, 5 cows, and 5 horses, which was typical for the region. Michael died on November 7, 1817 at the age of 66. Congress finally issued pensions for Revolutionary War state militia members and their survivors. After several petitions, they granted Leah a pension in 1842, two years after her death on June 24, 1840 at the age of 88. Their son, Cornelius, and grandson, Michael, would continue to farm the Monsey homestead. However, after Michael died in 1863, with 2 of his sons fighting in the Civil War and another preferring to take up a trade, the family lost the farm. End Notes1. Riker, J. (1904). Revised history of Harlem (city of New York): Its origin and early annals, prefaced by home scenes in the fatherlands; or, notices of its founders before emigration. Also, sketches of numerous families and the recovered history of the land-titles ... New York: New Harlem publishing company.

2.GREEN, F. B. (1886). HISTORY OF ROCKLAND COUNTY. HANSEBOOKS, pg. 10 Retrieved from www.archive.org 3. 1. Riker, J. (1904). Revised history of Harlem (city of New York): Its origin and early annals, prefaced by home scenes in the fatherlands; or, notices of its founders before emigration. Also, sketches of numerous families and the recovered history of the land-titles, pg. 68. New York: New Harlem publishing company. |

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed