|

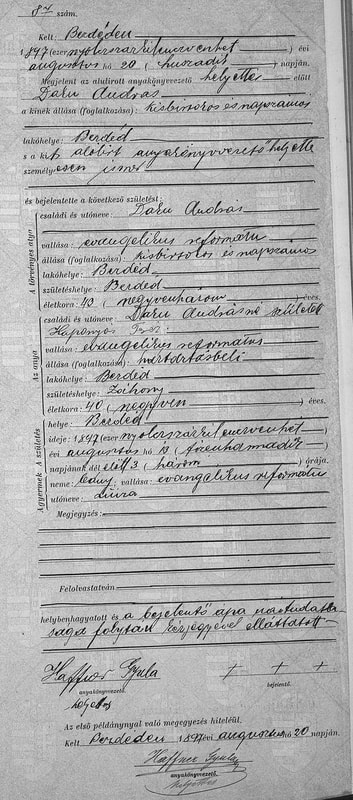

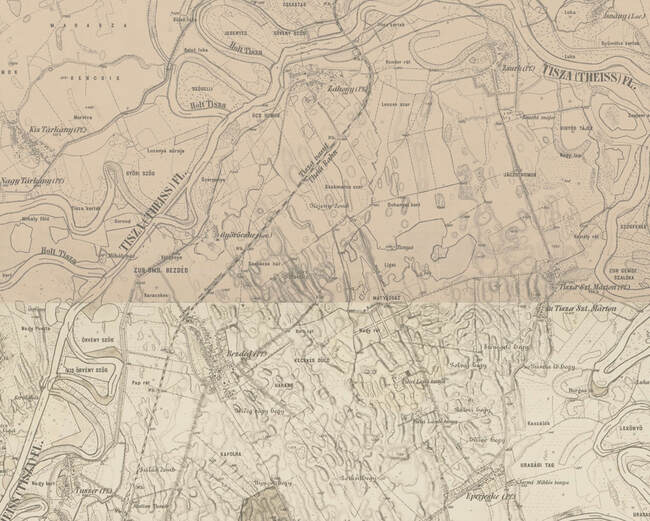

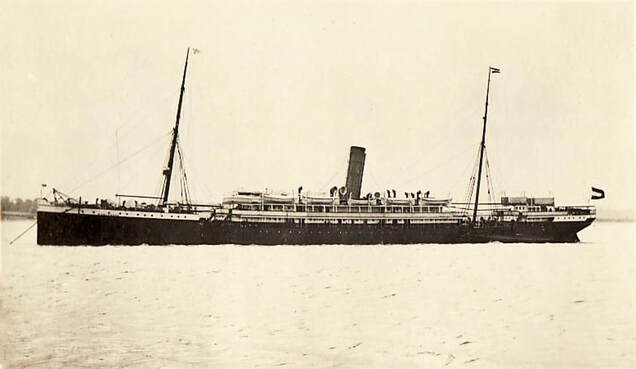

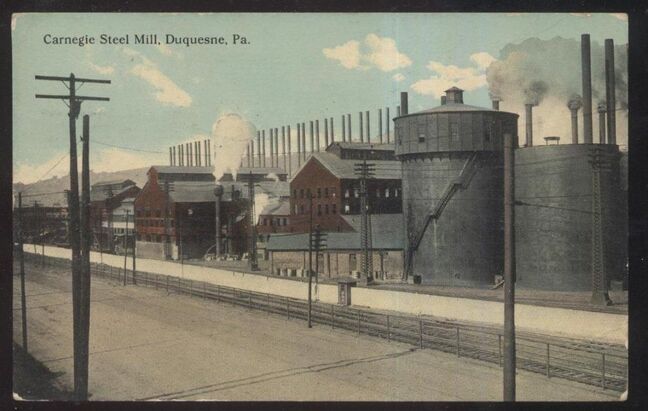

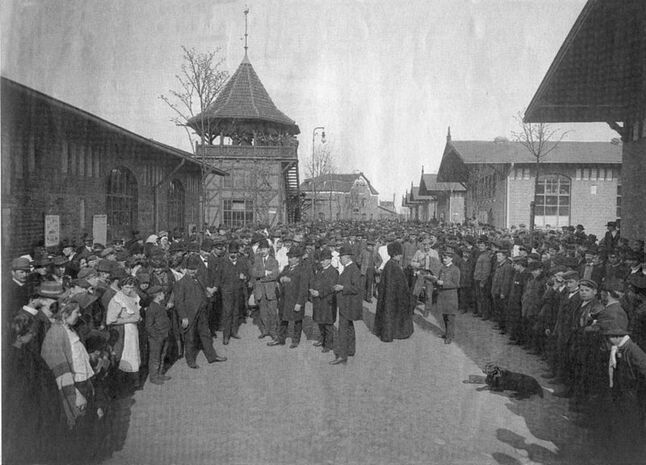

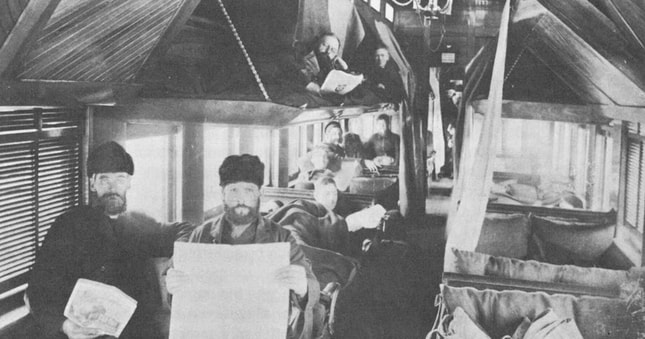

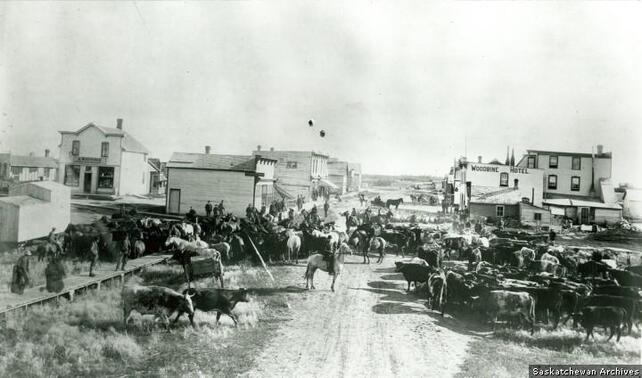

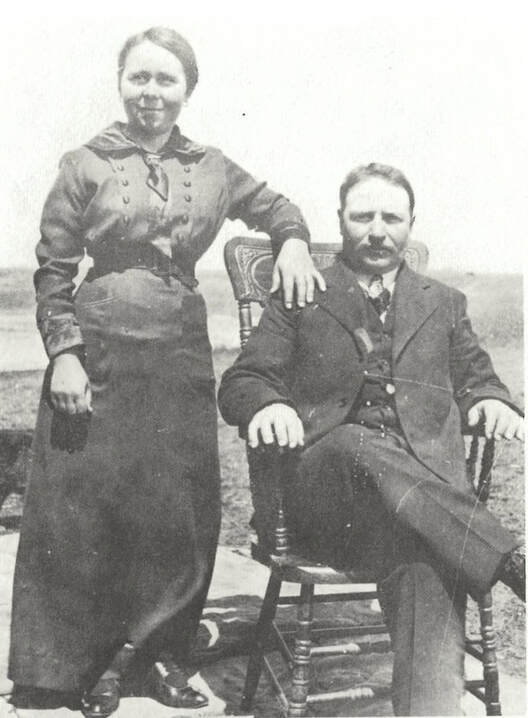

Canadians have memorialized November 11, 1918 for the signing of the armistice that ended the Great War, a four-year conflict that devastated nations and slaughtered as many as 19 million people. Over half that number were young men who perished in horrific battles, mowed down by machine guns or asphyxiated by poison gas, while famine and deprivation claimed millions of civilian lives. That date also marks a personal tragedy in my family, not as a result of the war but from an even more calamitous event. Researchers today estimate that the Spanish Flu snuffed out between 50 and 100 million lives, primarily the young and healthy, in only a few short months. Pregnant women or women who had recently given birth were especially vulnerable, such as my great-grandmother. BezdédDaku Lujza was born on a Friday, August 13th, 1897, to Kaponyás Terézia and Daku András in the village of Bezdéd near the Upper Tisza river, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. She was the family's youngest child and only daughter, with four older brothers: Sándor (b. 1880), Elek (b. 1884), András (b. 1887), and Lajos (b. 1890). Her father's family had lived in Bezdéd for centuries and she had countless cousins throughout the several small villages in the region. Seven days after her birth, Terézia and András bundled up Lujza and carried her to a Reformed Church, where the ordained minister christened her in a basin of water and recorded her birth. As a baby, Lujza may have worn a little shirt sewn from her father or brother's worn underwear, decorated with a pink, hand-crocheted collar and a crocheted bonnet decorated with a pink ribbon. For the first few weeks, cousins and neighbors would have brought Terézia and her family food while she recovered from childbirth and nursed her newborn. Since work never ceased, after a few days Terézia bundled her baby up tightly and tied her into a pillow, the arms and legs straightened and restrained, so she could keep the infant safe and nearby throughout the day. As Lujza grew older, she likely toddled freely around the house and yard while Terézia cooked the meals, washed the clothes, tended the vegetable garden, and hand-churned the milk into cream and butter. The household was very formal and puritan. András addressed Terézia as "Dakuné asszoney" and Terézia addressed her husband as "Daku úr", or essentially, "Mrs. Daku" and "Mr. Daku". They gave Grace at every meal, attended church on Sunday, observed the Sabbath and read the Bible repeatedly. There was more to their culture than just religion, however. The Daku family were literate, about half of Hungarians in region were at this time, and they composed poetry, played music, and danced in their few moments of leisure. Sándor described their home in Hungary: "Our father, while at home, was a member of the old guild of bootmakers and, because of this, until the time I was big enough to hold the handles of a plough, mother operated the small farm. In accordance with the prevailing practice of the time, father started work at six in the morning and continued until eleven or twelve at night. This he did also because of the tradition of the women of the community by which they would do their spinning in the long winter evenings in the bootmaker's workshop. Also, the farmers used to call in to discuss politics and other public affairs. It was there that I heard, for the first time, about the brilliance of Louis Kossuth, the rest of the heroes of the War of Independence, and its events. It was there that I was first told by the pious peasants that war was in the offing. In the first instance, because very many young men had been called up and secondly, because Louis Kossuth had returned from Italy in disguise, in order to visit every community and call upon the people to rise again and fight for freedom." On those long winter evenings, with her mother spinning flax into linen in the workshop and father and brothers stitching pieces of leather together into boots, Lujza may have played at their feet, listening to the news of the village. This talk of war certainly helped push the Daku family out of Hungary but other considerations may have been rising land prices from the population boom or falling prices for goods and produce driven by rapid industrialization, Regardless of what pressures motivated the family, they began to consider leaving Hungary and they were not alone. The Magyar DiasporaTerézia had been born in Záhony, 6-kilometers north of Bezdéd and although her parents had passed on she still had family there, including an older sister, Kaponyás Rebeka, who had married Czeto Istvan. In the late April of 1900, Istvan and Rebeka departed Hungary for Canada, along with their son, Sándor, and his wife, Maria, and their other children, András, Rozália, Anna, and Julia, and grand-daughter, Rosa. A year later, in April 1901, 3-year-old Lujza may have accompanied her family to the Royal Hungarian State Railway station. On that day, the family bid farewell to her 20-year-old brother, Sándor, who took the train south and west to Budapest and north, out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to the German city of Bremen, where he boarded the steamer ship, S.S. Karlsruhe. On March 4th, 1901, Sándor may have been standing on tiny portion of the deck permitted to steerage passengers to view the Statue of Liberty as the ship steamed through New York Harbor towards Ellis Island, where he was examined, cleared, and entered the United States of America. Once he was settled in America, Sándor wrote home encouragingly and Lujza soon said goodbye to another brother, Elek. The 17-year-old departed Europe from the German port-city of Hamburg aboard the steamer Furst Bismark and arrived in New York on September 20th, 1901. At home, 14-year-old András and 11-year-old Lajos would have had to pick up the slack for their missing brothers. Sándor and Elek found work with the Carnegie factory in Duquesne, Pennsylvania and wrote home about how they were well-paid in gold, which enticed other young men in Bezdéd to leave for America. Perhaps they two young men expected their parents to be excited by the news as well and to join them there but it appeared that Terézia and András wanted to be farmers, not factory workers, and they wrote back about a small farm for sale near Bezdéd. However, then a new opportunity arose. Austria-Hungary had banned pamphlets and advertisements promoting emigration to Canada; the Empire was simply losing too many workers. However, nothing prevented people from receiving letters from family abroad. Rebeka and Istvan Czeto had settled in the Whitewood area of the Saskatchewan District of the Canadian North West Territories, alongside some families from Bótrágy, a village which lay 25-kilometers west of Bezdéd. One of those settlers, János Szabó, established a Protestant, Hungarian Colony south of Whitewood named Bekevar, intended for about 200 settlers. He and his compatriots began a letter writing campaign home to attract fellow Bótrágians but were unable to attract enough families. It is possible that the Rebeka heard about the nearby colony and wrote home to her sister. Regardless of how they learned about Canada and Bekevar, András and Terézia learned that Canada offered a quarter section for only $10 and that they would have the option of buying a neighboring quarter section once they had sufficiently improved the land. Moreover, they already had family in the region and more from Bezdéd intended to join the colony. The deal was far too attractive to resist. They sold their property and tools, and prepared to leave their home forever. Canada offered $5 for every immigrant delivered to the Canadian West so German steamship-line agents skulked across the Hungarian countryside to spread word of Canada and offer to arrange transportation. András and Terézia may have contacted one of these agents, who organized passage by train to Hamburg, where they would rendezvous with another agent, who would assist them in boarding their steamship. A Journey of 11,000 KilometersIn early June 1902, András, Terézia, András Jr, Lajos, and Lujza made their way to the train station one last time. Following the standard advice sent back from friends and family, they likely disposed of much of their personal property and now carried only a few possessions with them, intending to purchase most of what they needed in Canada. Still, their backs likely bent with the weight of trunks filled with clothing, feather-beds and household utensils. The Daku family did not travel alone from Zahony on their trip to Bekevar, several families also traveled the same route, although most were bound for Winnipeg, not Saskatchewan. The Royal Hungarian State Railway transported the family south from their small village of a few hundred people, past the small, neighboring villages of Tüzér and Komoró and then around the much larger towns of Kisvárda and Nyíregyháza and out of the Szabolcs province, which was probably farther than any of the family had ever ventured. After a few hours of bumping, lurching travel, they turned west through Debrecen and Karcag and across the Carpathian Basin to Budapest. rumbling down the tracks at 50 kph, stopping at small train stations across the Hungarian kingdom. With the stops, the journey likely lasted throughout the day and night and into the next day, finally delivering the Daku family to Nyugati Pályaudvar, one of the main railway stations in the city. The railway station was at the centre of this city of almost 800,000, near the Danube River, by far the grandest sight of human civilization that Lujza and her family had ever beheld. From there, they would have boarded another train to Hamburg, a journey of a few days, which took them through Vienna, the capital of the Hapsburg Empire, a magnificent imperial city of 1.7 million people, the 6th largest city in the world. The family was to depart Europe from Hamburg aboard the S.S. Armenia, a 399-foot long, single-stack steamship built in 1895 and operated by the Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft (Hamburg-American Packet Travel Actien Company or Hamburg-America Line for short). The Hamburg-America Line transported such huge numbers of East-European emigrants that the company constructed BallinStadt (Ballin City) in 1901, named after the director-general of the company, a facility with a dozen living barracks, a dining hall, a synagogue and two churches. In 1902, BallinStadt housed up to 1200 emigrants at a time, who might stay as long as a few days waiting for their ship to depart. A Hamburg-America agent would have met the Daku family at the train station, examined their papers and then guided them to BalinStadt. The staff would have then required the family to bathe while they disinfected all their clothing and belongings with carbolic acid. Afterwards, they were assigned bunk beds within a ward, which they would have shared with three or four other families, whom were likely also Hungarian and Protestant. However, Lujza and her family would have been exposed to multicultural life during meals and recreation, as their fellow emigrants included Galacians, Hungarians, Russians, Germans, Romanians, and Bulgarians. The family took their meals in the dining hall, where they ate plenty of bread and meat and they may have attended a dance on the evening before their departure. On May 31st, 1902, Lujza and her family boarded the S.S. Armenia with almost a thousand other passengers, which included 254 children under 14 and 82 infants. Carrying their belongings, the family walked up the gangplank onto the ship and then immediately climbed below to the steerage deck. The family would have chosen their tiered cots and settled into to their small corner of the ship, as more and more passengers shoved in until there was little room to move about. The deck was freshly scrubbed but there were few windows and little fresh air. With the smells of smoking, cooking, perspiration, bodily waste, and seasickness, the air became awful to breathe and passengers fought to take a turn on the tiny portion of the upper deck reserved for steerage passengers. The crew fed passengers meals of pigs feet and rancid herring from huge kettles, which they served into dinner pails along with bread that was so uneatable that some simply threw it into the ocean in protest. Although it was unlikely Lujza could witness the passage from her place on the steerage deck, the S.S. Armenia steamed up the Elbe and out to the North Sea, then down the English Channel to Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. At that port, even more passengers joined the ship: over 140 Syrian men, women, and children bound for Montreal. At last, the S.S. Armenia steamed out into the Atlantic. After leaving Hamburg, Lujza and her family would spend almost two weeks on the ship. They were fortunate that there were no major storms during their passage, although that didn't mean they may not have encountered rough weather from time to time. A wave that rocked the boat could easily send people tumbling from their cots and scatter belongings across the deck. During the passage, Lujza would have heard the chatter of a dozen different languages and listened to songs and music from several cultures. There would have been people dressed in more modern 20th century garb and others dressed in peasant attire and sheepskins, the men with long hair greased with lard, the women bundled in patterned shawls. The S.S. Armenia arrived at Halifax on June 13th. The steerage passengers, clean and well-scrubbed at the beginning of their voyage, stumbled off the ship in a bedraggled state. They underwent a cursory medical examination and immigration and Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) agents directed them onto waiting colonist cars, which would take them west. Before their departure, András and Terézia likely had to buy sufficient food to last them the several days of the trip to Saskatchewan. Once on the colonist car, they sat on the hard rowed bench seats, possibly padded with blankets and pillow brought with them, and took turns with other families to sleep on the fold out bunks in the back. They would have shared a single stove in the back of the car for cooking and 2 toilets with the other passengers. Accustomed to the well-cultivated and populated landscape of Europe, András and Terézia may have been dismayed at the raw and rugged state of the Canadian wilderness through which they passed, Even the cities and towns were rough and small compared to the large, stately cities that they had seen on their trip across Europe. Whether the young Lujza was entranced by these sights or merely bored with yet more travel is a mystery. When the family finally passed from the vast forests of northern Ontario onto the enormous, seemingly endless grasslands, they may have felt terribly isolated and realized the conditions in which they were going to live. Most of the Hungarians and Galicians disembarked the train at Winnipeg, a respectably large town of over 40,000 people. However, the Daku family continued their journey for one more day, stepping off the train at Whitewood. The Hudson's Bay Company had established a trading post here in 1891 and by 1902, the town's population had climbed to 400. BékévarAndrás and Terézia were fortunate compared to many other settlers. With family and fellow Hungarian colonists already here, they likely already knew of a good claim and may have even been met by a friend or family member to guide them to their new home. András likely rented or purchased a team and wagon, bought the supplies they needed to survive on their isolated homestead. and headed south down whatever rudimentary track that the previous settlers had manage to carve out. After selecting their land and traveling to Regina to stake their claim, the family wrote to Sándor and Elek to join them in the colony. Since every man over 18 could stake his own claim, the two sons quickly rejoined the family. Upon their arrival in Canada, Lujza became Louise, András became Andrew, Terézia became Teresa, Sándor became Alexander, András Jr. became Andrew Jr, Lajos became Louis but Elek remained Elek. For the first several months, 5-year-old Louise and her family likely lived with several other families in a makeshift log building. With help from fellow colonists, her parents quickly built a log house of their own but Louise still shared a single sleeping room with her parents and brothers, although they now had a separate kitchen. Shortly after, they likely added a small upper floor. By 1903, Bekevar consisted of 45 homesteads. To claim their land, Andrew and Teresa needed to accomplish several milestones, as set out in the Canada Dominion Land Act:

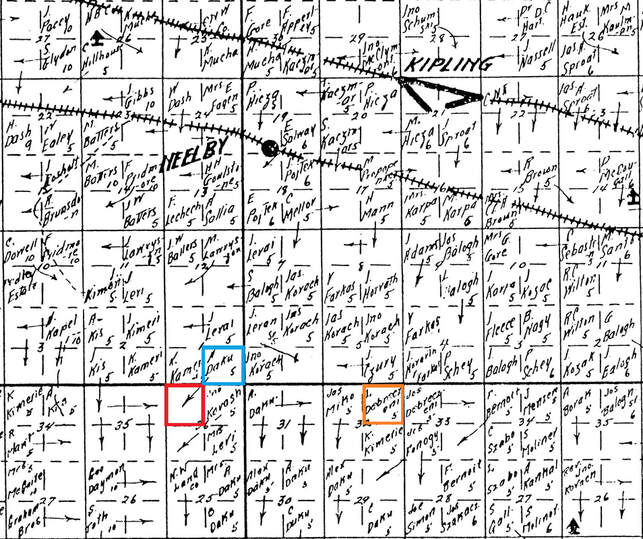

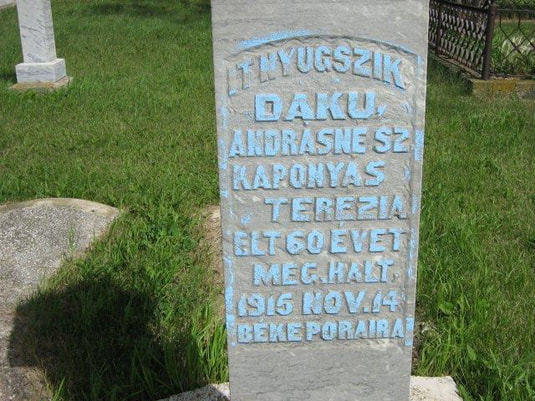

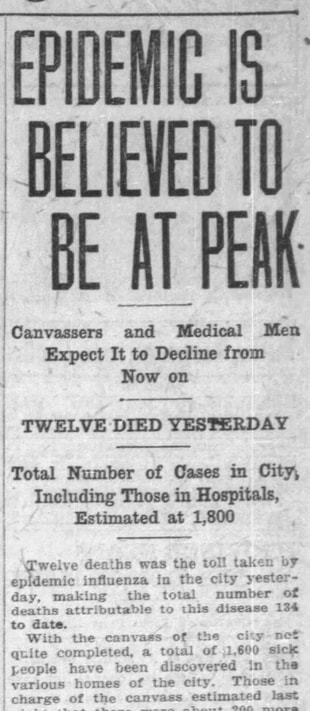

Louise's first chores were to collect any strayed livestock, although she would soon be put to work to feed and milk the cows and take them out to pasture before she left for school. Although men and women had a clear division of labor, with so much to do and so much land, Louise likely helped her brothers pick stones from the fields while her mother joined her father behind a plow to break the tough prairie sod. On August 25th, 1904, Andrew filed for a homestead in Township 12, Range 6, Section 36, which he successfully patented. Since every 2nd quarter was CPR land and available to purchase if he successfully patented his first homestead, he purchased an adjoining 160 acres. By 1920, his sons, Alex, Andrew Jr, Elek, and Louis also claimed homesteads as well as purchased additional quarters. Surrounding the Daku homestead were several families with whom their children would intermarry: Debreceni, Kimeri, Fonagy, and the other Daku family. In 1907, the Canadian Northern Railroad built a rail line close to Bekevar and in 1908, they constructed Kipling Station, named after Rudyard Kipling, who had visited Regina in 1907, which made it far easier for the local farmers to get their crops to market; some even drove their crop to the station by truck. A town of the same name quickly grew around the railway station. Kipling soon became the predominate commercial hub for the region and, as elderly Hungarians retired in town, more of the Hungarian social and religious life relocated there. The community petitioned for a school in 1905 and in 1906 the government built the Magyar School for the 20 school-aged children. Louise was about 9 when she first attended school in Canada and since her teachers were English-speakers, they provided her first formal English education. The school also served as a prayer-house and the family would travel there every Sunday before the Bekevar Church was completed in 1912, when Louise was 14. With no Hungarian Reformed Church in Canada, most of the Hungarians joined the Presbyterian Congregation, although many would become Baptists. When attending services at the Bekevar Church single men sat in the choir, single women sat downstairs on the left, married women sat on far left and married men sat on the right. Louise may have been one of the first to have been confirmed in the Presbyterian faith at the Bekevar Church, after which she would have sat in the back with the single women. Courtship and MarriageAfter services, the young people played games and walked home together in groups. It might have been then when Louise first became interested in Lawrence Debreceni, the son of József Debreczeni and Juliánna Jonás. In 1912, Lawrence was 19 years old, almost 6 years older than the 14-year-old Louise. His family was from Karcag, a much larger and more cosmopolitan town than the tiny village of Bezdéd. Lawrence’s family was the wealthiest in Bekevar and had migrated to Canada through New York in a 2nd class cabin, avoiding the purgatory of steerage. They had arrived with $4000 cash and instead of constructing a rough log house, they hired craftsman to build them a proper framed home. However, like the Daku family, they were bookmakers who had worked their way up from peasantry. Groups of young men would commonly call on families with daughters, allowing the young people to mix under the supervision of the parents. However, at this time Louis's oldest brother, 32-year-old Alex, also courted Lawrence's sister, 28-year-old Maria Debreceni so the families may have been mingling on a social basis. Regardless of how their courtship began, Lawrence would have then began visiting alone, signaling his intention to court Louise. Louise may have also attended the many dances in the community, which usually followed weddings or were sometimes organized by word-of-mouth after church services. And there was a whirlwind of weddings, as Louise’s brothers and cousins all married, as well as many other young people in the community. Her brothers Alex, Elek, and Louis regularly played at these events as the Daku Band, where they earned $1.50 each plus 3 glasses of wine or brandy. Starting at 8 in the evening in a log barn, they would play the Csárdás, a traditional Hungarian folk dance, or waltzes until the morning. Louise would have worn her Sunday dress and Lawrence would have invited her to dance with a bow, and a formal invitation of “may I have the pleasure”? In early 1913, Lawrence asked Andrew and Teresa's permission to marry Louise, which he granted, and then informed the minister, who announced the engagement on 3 consecutive Sundays in Church. As the wedding day neared, the couple's Vőfély or Master of Ceremonies donned a bright ribboned hat and rode about Bekevar in a decorated buggy to invite everyone to the ceremony. On the day of the wedding, Andrew and Teresa hosted a dinner for family and friends, after which the bride and groom left separately for Bekevar Church, where they were married. After the wedding, everyone traveled to the groom's house, where the women of the community hosted an elaborate dinner, followed by dancing, music, poetry and other festivities. About the same time Louise and Lawrence married, their older siblings Alex and Maria also wed. Not long after their own wedding, Alex quit the Daku Band at the urging of Maria. He had played the cimbalom, an Hungarian instrument popular among the gypsies, but Maria complained that there was too much drinking at the dances and he was staying up far too late, which interfered with his farm-work. A New FamilyLawrence and Louise would farm a quarter-section that lay between their two families and begun by building their new house together. Like her mother, there was too much work for a strict division of labour, and she would have harnessed up horses and helped in the field as well as fed the animals, milked the cows, cared for the garden, cooked the meals, laundered the clothing, and cleaned the house. Louise would spend much of her time hand-churning the milk into cream and butter. Then, once a week, she would harness the horses to the buggy and drive into Kipling, where she would sell her dairy goods for enough money to cover the weekly grocery bill. These responsibilities were soon even more challenging as the 16-year-old Louise became pregnant and delivered a baby girl, Mary, in late 1913. A few months later, she was pregnant again, and added a son, Joseph, to the family on October 27, 1914. As with her own birth, the women of the community brought meals to the family and helped with the chores while she recovered from childbirth. She would have baptized her children at the Bekevar church and since religious observance was so important, continued to attend services and breast-fed her infants under a cloth during the long sermons. The joy of the birth of her second child was soon mingled with grief, however, as her Aunt Rebeka died only a few days before Christmas, on December 19th, 1914 at the age of 61. Tragedy would strike even closer to Louise’s heart when her mother, Teresa, died less than a year later on November 14, 1915, at the age of 58. They buried in the Bekevar Cemetery. Andrew Sr, would live with his youngest son, Louis, and his family until 1933, when he would pass away at the age of 79. In 1914, a world war erupted. As a member of the Commonwealth, Canada was automatically at war against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Louise’s many cousins back in Bezdéd would have been conscripted into the army to fight against Russia, Britain’s ally in the war. Her parents fears of conscription finally came true, although much later than they had expected. Although urged by Britain to not act against former subjects of Austria-Hungary, Canada viewed them all with deep suspicion and invoked the War Measures Act to restrict their movements. This did not overly affect the Hungarians at Bekevar, although the hostility of their government and possibly some neighbours may have created worry and tension. Those affected were mostly ethnic Ukrainians from the Empire. Canada arrested almost 8,600 unemployed young Ukrainian men who attempted to cross into the U.S. to find work and sent them to one of 24 concentration camps. Life went on, of course, and Louise was soon again pregnant. Her daughter, Julia Debreceni, was born on November 1st, 1917. The 20-year-old young woman had 3 children under the age 4 and a farm to run so life must have been a challenge, to say the least. However, times were also good. Between 1915 and 1918, the price of wheat almost doubled and with butter and cream covering most household expenses, the growing family prospered and must have been hopeful for the future. The Spanish FluIn June 1918, the Regina Leader-Post published only a few stories of the Spanish Influenza. However, the epidemic was happening far away and the newspaper even portrayed it as a good news story; a flu that was doing its part to help the Allies to win the war effort. On July 27th, the Leader-Post published another story about how the Flu rapidly spread through the German Army, to the point where it postponed an offensive action. On July 6, the paper further reported the Spanish Influenza spreading throughout the German civilian population. On July 9, the Flu was hampering the German army across the whole front. On July 11, the paper reported that even Emperor of Germany and his staff were down with the disease. By August, the Spanish Flu had crept closer to the Canadian Prairie but the newspapers still reported it lightly, perhaps to not distract from the war effort. A story announced new health measures in New York City, including a caution to avoid kissing, under the playful byline "Someone's always taking the joy out of life". Then in September, the papers published far more serious stories. The Prime Minister was Great Britain and his staff were very ill. There were seventy deaths in twenty-four hours in New England. Five hundred U.S. soldiers were pulled from transports, sick with the Flu. Nine sailors stationed in Quebec died. Then, after declaring the Flu almost over, the U.S. army reported 3,000 new cases among it's ranks with 112 deaths. By the end of September, the U.S. army reported that over 29,000 men had been afflicted and there had been 530 deaths. However, perhaps deliberately, the U.S. Army had significantly under-counted the number of soldiers afflicted. By the end of 1918, over 45,000 U.S. soldiers had died of the disease. By October, the Spanish Influenza had made it's way to Saskatchewan. Predictably, businessmen would attempt to make a little money from the growing anxiety before the full force of the Flu hit the region. The newspapers ran advertisements for products and services that claimed to prevent the flu, including eucalyptus oil, menthol bags, and fumigation services. Business would later include notes in their advertisements that they were safe to visit because they regularly disinfected or ate onions as a preventative. On October 2nd, sick passengers were pulled off a train that arrived in Regina and quarantined. On October 7th, the newspaper reported that the Flu had appeared in the town of Willow Bunch. On October 8th, four cases were reported in Saskatoon. However, despite a few cases now showing up in Regina, doctors decided not to close public places, such as churches and schools, and urged the public not to panic. The Flu's first victim in Regina was Robert Callander, a local drayman. His symptoms began with a high fever, headache, aches, and chills. Although not reported in the newspaper, he likely died from pneumonia, and the newspaper under-stated the true horror of the disease. “When first seen, the patient’s face was flushed, the nostrils blocked, the tongue heavily coated with thick whitish fur at the edges with a brown centre, the lips blue, the throat dark red, the skin hot and moist, the temperature 103 or 104 degrees ... As time went on, quantities of blood-stained expectoration or nearly pure dark blood was expelled, respiration became laboured, face and fingers cyanosed [turned blue], active delirium came on, the tongue became dry and brown, the whole surface of the body blue and the patient died from failure of respiration.” On October 8th, the government of Saskatchewan declared that the Spanish Influenza was a "reportable disease", which meant that existing regulations would apply to the epidemic for the control, notification, prevention, isolation, quarantine, placarding, and disinfection of contagious and highly infectious diseases. At the same time, the Regina general hospital opened an emergency isolation hospital. Despite these measures, the hospital board stated that the Flu was no more dangerous than previous years' flu and that there was no reason for panic. However, despite several days of stories describing the mounting toll of the disease, Saskatchewan refused to close the schools with the statement that children were largely not susceptible to the Flu. Indeed, stories from various newspapers continued to report that the elderly were most susceptible and ignored the mounting evidence that it was the young and healthy that were the most vulnerable. Moreover, although the Spanish Flu was a reportable disease, some physicians deliberately did not record the real cause of death when a person died from the Flu. A quarantined house meant that people could not leave to work, which would have created severe hardship for many families. The Hungarians in Bekevar may not have been fully aware of the impending epidemic. Few would have read English-newspapers. Although as people in Saskatchewan began to die of the disease, they certainly would have heard about it through word-of-mouth. Whether they were worried or felt safe on their removed farms, the daily toil of day-to-day life likely gave them little time to dwell on it. November 3rd, 1918 was cool and dry. The temperature was barely above freezing as Lawrence and Louise bundled up their 3 children, harnessed the horses to the buggy, and rode to the Bekevar Church. As was the custom, Louise sat on the left side of the church with Mary, Joseph, and Julia, who had just celebrated her first birthday days earlier, while Lawrence sat on the right. The sermon would have probably been long, as usual. Julia may have fussed and Louise breast-fed her underneath a blanket. A neighbor, friend, or even family member in the church may have been coughing and sniffling with a bug that they had picked up on a recent trip to town. After the service, Mary and Joe may have run around with the other young children while Lawrence and Louise caught up with family and friends. Within a day or two after that service, Louise would have begun to feel poorly. She likely had the chills and her cough began to rapidly worsen. In a few days, she may have been too sick to rise from her bed. Lawrence may have rode for the doctor but there was nothing anyone could do. Louise died on the afternoon of November 11, 1918, at the age of 21, leaving behind a husband and 3 very young children. Louise's family buried her near her mother in the Bekevar Cemetery. She was only one of the 55,000 Canadians killed by the Spanish Flu. Aftermath and LegacyLeft with 3 young children, Lawrence turned to family for help. Alex and Maria Daku had no children of their own and took in their 2 nieces and nephew. In April 1920, Lawrence boarded the train for Halifax, where he embarked on the S.S. Canada bound for Liverpool on his way back to Hungary. He stayed a few months in Budapest, where married Julia, a 25-year-old Roman Catholic Hungarian from Szimo, which the Allies had separated from Hungary as part of Slovakia. Months after Lawrence and Julia returned to Bekevar in late November 1920, Mary and Joseph returned to live with their father and new step-mother but Julia remained with the Alex and Maria, who raised her as their own daughter. Lawrence was active and served as a curator on the Presbyterium, partnered in a Kipling implements store in 1921, and served on the Kipling Colonisation Board in 1926, which worked with CPR to settle Hungarian immigrants in the community. Lawrence Debreceni passed away on January 19, 1939 at the age of 46. Mary Debreceni married Frank Fónagy on January 14 1932. They were married 49 years, until Frank's death in 1991, and had 6 children together. Mary passed away in 1995. Joseph married Olga Toth on June 1, 1939, and they were married 48 years until his death in 1997. Alex and Maria Daku saw their daughter, Julia, marry Bálint (Ben) Daku on January 20th, 1939. Ben and Julia were married for 73 years, until her passing in 2011 at the age of 93, and had 7 children and 14 grandchildren. Alex Daku coached his granddaughter, Eileen Daku, on her confirmation vows in the Hungarian language and on May 7 1959, he and Maria watched her confirmation in the Bekevar Church, where her grandmother had been confirmed back in 1912. BibliographyKovacs, Martin Louis. Peace and Strife: Some Facets of the History of an Early Prairie Community. Kipling: Kipling District Historical Society, 1980.

Hollos, Marida. “Families Through Three Generations In Békévar.” Bekevar, n.d., 65–126. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt22zmdsq.6. Kresz, Mária. “Békévar, Children, Clothing, Crafts.” Bekevar, n.d., 127–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt22zmdsq.7. Vintze, Etienne. “Békévar, Yesterday and Today.” Bekevar, n.d., 257–302. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt22zmdsq.10. Berton, Pierre. The Promised Land: Settling the West, 1896-1914. Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2002. Steiner, Edward Alfred. On the Trail of the Immigrant. New York: F.H. Revell Company, 1906. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/40887/40887-h/40887-h.htm#page_030 |

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed