|

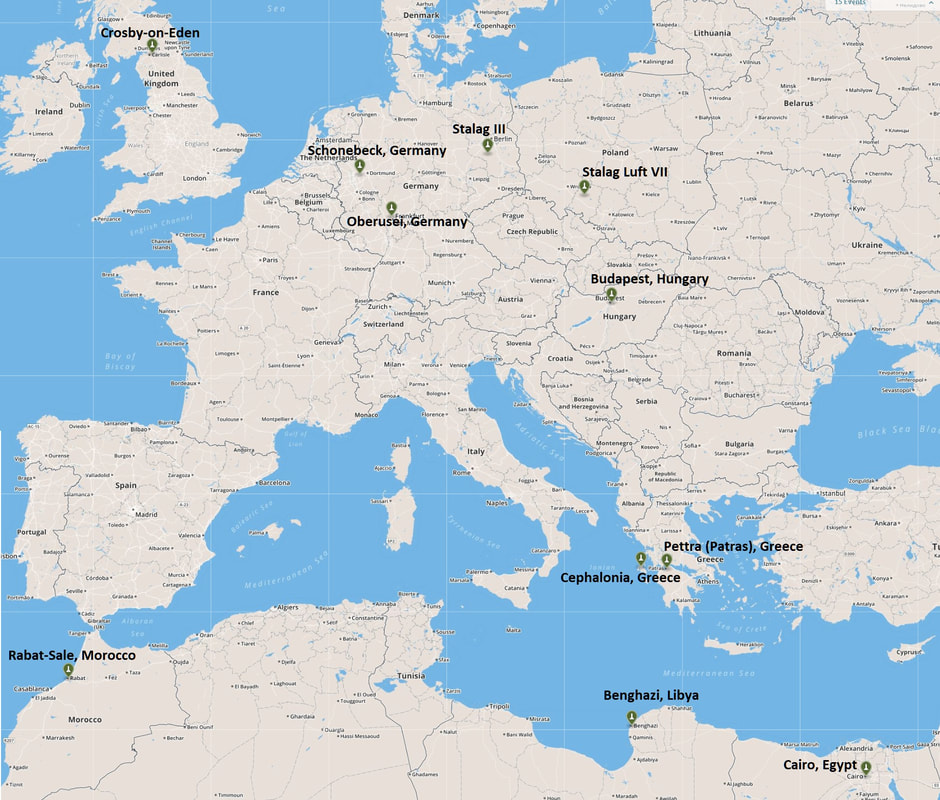

Charles Gordon Goodwin "Pat" Davis was my great-uncle, my Grandma Grace's younger brother, who sadly died at the age of 47 on November 6th, 1969 from medical complications of his injuries in World War II. He left behind a wife and six children. Below is his account of his experiences during the war, shared with me by my cousin, Dena, whose father, Arnold Davis, served valiantly in North Africa and Sicily, and Italy. Pat DavisAfter graduation from high school in 1939, I worked on the farm until December of 1940. In December of 1940, I went to Malartic, Quebec where I became employed as a Ballmill helper and a Filter Operator. At this time, I enjoyed good health and had successfully passed the physical examinations that were required by the Department of Mines in order to be employed in the mill. On January 5, 1941, I proceeded to North Bay, Ontario, which was the closest R. C. A. F. Recruiting Centre and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. I was accepted for air crew training and was dispatched to Manning Depot at Lachine, Quebec. Upon completion of our training at Manning Depot, we did a tour of ground duty at Rockcliffe, Ontario. From Rockcliffe, we were posted to Belleville where we took our initial training. From Belleville, we were posted to No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School at Windsor Mills, Quebec, for training as Pilots. At Elementary School on September 2, 1941, I was forced down due to bad weather and, in landing in a grass field, hit a hole which I could not see, and the aircraft turned over and was a complete write-off. I was injured slightly in the arm only. I successfully completed Pilots Initial Elementary Training Course on September 23, 1941, and was posted to No. 8 Service Flying Training School at Moncton, N. B. I successfully completed the Service Flying Training Course and was graduated as a Sergeant Pilot at the end of January 1943. From No.8 S. F. T. S., I was posted to No.1 G.R.S. in Summerside, P.E.I., where I successfully completed an extra navigation course on April 18, 1943. We ere then posted to Halifax and proceeded overseas in the first part of May 1943. Upon arrival overseas, we were posted to Bournemouth. England which was a holding depot for the R. C. A. F. overseas. During the first part of July 1943, we were posted to No. 18 Advanced Flying Unit. After completion of my course I was posted into the Reserve Flight for testing aircraft for use by other students for night flying duties. On September 12, 1943, I again had a flying accident in which, while testing an aircraft, we lost one engine on approach and were unable to recover and, as a result, we crashed short of the airfield - wiping out the aircraft and giving ourselves a thorough shaking up. On September 14, 1943, we were posted to No. 9 Operational Training Unit at Crosby-on-Eton. Here we underwent a conversion course on Beauforts and thence to Bullfighters. We completed our Operational Training Course on the 11th day of the 11th month, 1943. I had volunteered for service in the Middle East and received a temporary posting to 204 Squadron at Port Ellen in the Hebrides. On the 7th of January 1944, I took off from Port Ellen and proceeded to Portreath and we spent several days in Portreath due to bad weather. We finally left Portreath for Rabat Sale in French Morocco on the 14th of January, arriving Cairo West on the 18th. We again went into a holding unit at 22 P. D. C. at Elmaza outside of Cairo. During the early part of 1944 was posted to Heliopoulis and assigned to do test flying on aircraft that had been in for major maintenance repairs. I continued to fly in this test flight until the early part of April when I was posted to R. A. F. Shallufa at No. 5 Middle East Training School for a Refresher Course on Rockets. On completion of this course I then was posted to No. 3 Aircraft Disposal Unit out of Oujda in French Morocco. Our job was to pick up aircraft in Rabat Sale and transfer them throughout the Middle East. I joined 252 Squadron about June 15, 1944 and flew with them until being shot down on August 1, 1944.

The following is to the best of my knowledge and recollection the detailed events leading up to my capture and subsequent imprisonment by the German Forces during World War II: I. Events Leading up to Capture As a member of 252 Squadron (Flying Officer) flying Mark X Beaufighters in Coastal Command Middle East, I was assigned along with three other members of our Squadron to fly to Benghazi from Gambit to undertake a reconnaissance of the west coast of Greece. We arrived in Benghazi July 31st, 1944 and were subsequently briefed as to our operation. Take-off was at 4:00 a.m. August 1st, 1944, and all aircraft succeeded in taking off, joining up and proceeding to the search area. The search was to take us far north as the Levkas Canal with a search of all the intermediate harbours, including Pettras, before we returned to base. The Squadron Leader in charge of the flight decided to split the flight into two groups; together with the Squadron Leader I proceeded to search near Cephalonia, while the remaining two aircraft searched in other areas. We discovered two armed merchant vessels shortly after the other group had broken off. The Squadron Leader decided to attack without waiting for the other element to join us. He requested that I attack the second ship as they were sailing in line astern. I attacked the second vessel as instructed but as our timing was off slightly I received crossfire from both vessels. As my run-in looked good, I decided regardless of the fire to carry on and had my rocket switch set on pairs firing the first pair. Again, because my run looked so good, I decided to set my rocket switch to salvo and fire the remaining rockets at one time. After I pressed the rocket switch and before I could break off I received a direct hit through the windscreen which destroyed the gun sight and knocked me unconscious, wounding me in the head and left shoulder. Fortunately, I recovered consciousness before we flew into the water and was able to level the aircraft out and try to determine the extent of damage. Because of the hole in the windscreen, debris in my eyes and face, and the fact that my goggles were knocked off my helmet; I had difficulty in seeing my instruments to determine what damage actually existed. The oil pressure on starboard engine was dropping rapidly and I requested my navigator, Sgt. Waller, to check the engine to see what he could see from his position halfway along the fuselage. He informed me that the engine was on fire and that we were smoking in the port engine as well. In view of the damage I decided that we would be forced to ditch and I so informed my navigator. He sent out an emergency signal, and I proceeded to try and put the aircraft in the water. We ditched successfully and got into our two-man dinghy. We had the option of landing on some nearby islands but deciding the smaller island would not be inhabited, we decided to try for the larger island, Cephalonia, where there would be a better opportunity of contacting the Greek underground. Time was about 8:00 a.m. We were trying to make landfall at night so that we would make land undetected; however, the tide turned against us and we drifted back away from the island unable to make our landfall at night. Landfall was subsequently made late the next afternoon, under the watchful eye of the German Naval Station who took the opportunity to fire at us in the water. A reception committee was there to meet us when we finally made shore. II. Confinement on the Island of Cephalonia The Germans, at this stage of the war, were finding it difficult to supply their island garrisons and so life on the islands was fairly rough for the German troops. They, however, as in most cases when you were dealing with the front-line troops, treated us as one of their soldiers as far as food and cigarettes were concerned. They were desperately short of medical aid on the island and were unable to treat my wounds - a first aid man being the only medical assistance available. We were confined in a chicken house under guard, and I had an old iron bedstead with just springs on which to sleep. The second day of our capture, the Germans commenced their interrogation. We were on the island for seven days before we were transferred via ferry to the Port of Pettras on the mainland of Greece. III. Turnover to the SS Troops in Pettras The Navy turned us over to the SS in Pettras and we were confined in a political prison where the captured Greek underground members were confined. My navigator and I shared a cell in which you could stand up only, (you could lay down if we positioned ourselves side by side) and there was no light - - - - - - it was considered the "dark cell" treatment. There was one small crack beneath the door to which we laid our noses to get some fresh air. The door had spikes driven through it with the sharp points on the inside to prevent you from kicking it or trying to draw any attention to any personal need. We were given a bowl of soup and a slice of bread and a cup of ersatz tea every second day. During this time my navigator developed a case of dysentery and he was prevented from using a latrine; therefore, he had no option but to dirty himself, and we lived like this for some eight days. On the ninth day, they took me into an SS Major who began to interrogate me; he was unable to speak English but he had a Lieutenant with him whose English was impeccable. It was obvious that he was going to try to intimidate me because of the shouting and screaming he engaged in during the initial stages of the interrogation. However, this only angered me and made me more firmly resolved than ever that the information they wanted they would not have. After some two hours of this abuse, I was taken out by an SS trooper and, on my way out, I saw Waller sitting out on a bench in the hall and he was in a very weakened condition; I said to him "don't let the shouting and screaming fool you - - - - this guy has got nothing on the ball", and I received a clout with a rifle butt for my efforts. We were held in this confinement for a total of ten days before we were turned back to the Airforce. On being turned back to the Airforce, we immediately received better treatment and Waller was actually removed to a hospital because his condition was so severe. I received by first medical attention from a doctor who endeavoured to remove some of the shrapnel and glass from my eye, forehead and shoulder. By this time, my wounds had begun to fester and I began to feel feverish; however, their hospital accommodation was such that they could not take both of us in and I was transferred to Athens the following day. The Athens PW camp mainly contained Italians and there were no other British in the camp at the time when I arrived. My condition worsened and I had a severe fever for some eight days and did not know what was going on around me. There was an Italian doctor in the camp but he had no drugs nor other medical aids. I began to recover and immediately the Germans decided to plant what I am sure were "stoolies" in with me to try and get information from me. These men posed as British Army officers who had been sent in with foe Greek underground and were captured by the Germans. Their questions were too leading, however, and I felt that they were seeking information which would get directly to the Germans. Shortly after, Waller returned and was much improved in health. The Germans then decided to move us to Budapest to the main penitentiary which served as an Interrogation Centre. IV. Confinement at the Main Penitentiary in Budapest At this point I entered the period of time when I received the most severe treatment and abuse. I received the first interrogation the first day I was in the penitentiary by a man who thought was not a first-class interrogator. He insisted that I must give them certain information in order for the Hungarians to release us to proceed on to Germany. Upon my refusal, the screaming and shouting started and with the threat that before I left there they would have what they wanted. My first stint was seven days solitary confinement, and during this time there was a guard (whom we called Wimpy) who took every opportunity he could to beat the prisoners and treat them in any way that would hurt them. His favourite trick was to set the daily bowl of soup on the floor after he opened the door and if you made the mistake of taking your eyes off him he would promptly kick you in the head. After seven days in solitary, I received my second interrogation and the same abuse from the same Lieutenant, who then said "Well, we'll make you talk ------ we have a new place for you to go to", and I was put in the dark cell for seven days. You cannot imagine the mental tortures you go through under this treatment. Again, our food was a bowl of soup, generally watery cabbage soup, with one slice of bread that had margarine on it, and a cup of ersatz tea. Time stops and you must hang on to your sanity by finding even the smallest thing, such as counting bedbugs, nail holes in the wall, cracks in the floor, and recounting them and recounting them, all of which was done by feel as there was no light. After seven days dark cell, I was given my third interrogation by the same Lieutenant who informed me that he felt that I would now be ready to tell him all that I knew. I promptly told him what he could do, and I received a belt across the head. The interrogation was very short and I was given back into solitary confinement where I spent another seven days. At the end of this seven days, I was given my fourth interrogation and was subject to the same abuse by the same Lieutenant with the same theme. After working himself into a screaming fit, I was given another seven days in dark cell, and again I went through the mental tortures. I began to worry that as I was gradually becoming physically weak they might be able to break me. After seven days, I was again called in for my fifth interrogation and we went through the same old routine, only this time he had a new wrinkle ---- he said "I have something I want you to watch and I have some of your friends that are going to watch with you" so they took us out into the courtyard where they had three people standing up in American uniforms and they were shot in front of us. The story to us was that these were people who had not satisfied them and that these were the Hungarians who had shot them because they felt that they were spies. However, we had looked at the three victims and decided they were Jewish political prisoners dressed in American uniforms; and further that they were not Hungarian soldiers who had executed them at all, but Germans dressed in their uniforms. The Lieutenant had one more run at me, but we still were at an impasse, and, at that time, they decided to transfer us to the main interrogation center at Oberursel in Germany. V. Confinement at the Main Interrogation Centre at Oberursel near Frankfurt am Main This was the main interrogation centre for Germany where they processed thousands of allied airmen, American, British and other nationalities. They were better organized with a better class of interrogators. They were very subtle in their approaches. They confined us in solitary but they interrogated us quite regularly, generally at two-day intervals. Food here was somewhat better in that you received an extra slice of bread with jam, and a cup of tea in the evening, beyond the soup (which was a better quality) _and the break and the tea that you received at one other meal. I spent ten days here trying to match wits with a very smart man. We were then moved into the main compound and immediately we received some Red Cross food, which was most welcome. From here, they moved us to Stalag Luft 7, which was near the old Polish German border near a town called Kreutzburg. This camp was actually under construction at the time and we lived in temporary accommodation prior to occupying the main camp. Temporary accommodation consisted of small shacks that were held together with hooks at the corners. There were no bunks so you slept on the floor. However, here we at least received some Red Cross food which amounted to one parcel divided among four people per week. The German ration was one potato, one cup of soup and three slices of bread per day. During the night, the Germans turned the dogs into the compound. There were no latrines in the little shacks so you had to footrace the dogs to get to the latrine in the main area, and of course you had to race them back again. We were eventually moved into the permanent camp which was supposed to be escape-proof and proved so in our case. Initially the rooms were to have ten men but it was not long until the Germans began to add more bunks to the room and we wound up with 13 men in the space which was designed for 10 people. We had one small stove and one allowance or ration of briquets per day which amounted to two as I recall. We, therefore, tried to cook most of the food on small homemade burners that we made from milk tins. They were quite efficient but very smoky and as a result the air in the room was always very bad. About the time that the additional bunks were added, our rations were cut and we were now only allotted one Red Cross parcel per eight people, and we received one potato every second day, one cup of watery soup per day, and one slice of bread. In December we found again that our rations were cut. The German ration remained the same but the Red Cross parcels were now cut to one for 16 people per week. It must be remembered that these parcels were designed by the Red Cross as one parcel per one healthy person per week. Life in camp was a constant war against vermin, lice, bedbugs, and fleas. Shortage of water and fuel to heat the water, especially in the winter months, did not allow us to keep ourselves sufficiently clean nor to keep our clothing or bedclothing clean and vermin free. When the Germans issued Red Cross parcels they always stabbed the meat tins with a knife to ensure that you could not save them; this meant that the meat had to be eaten immediately or it would spoil. Practices such as this, along with the fact that it was difficult to keep clean, led to serious bouts of dysentery and other forms of disease. Notwithstanding, each man-made every effort to try and keep himself as physically fit as he could because he was not sure of what the future held and what we would be called upon to face. Probably one of the largest hazards to health was one's mental health. It is difficult to describe the effects of being a prisoner without actually having experienced it. The constant surveillance, the constant searching, rousing you at two or three o'clock in the morning to carry out searches, the threat of machine gun fire always pointed in your direction - - - - all of these things added to complete frustration. We did have news service in the camp from a radio, however, unfortunately for us, in January it broke down and we were without news for a period of four or five days. During this time, the Russians broke through and were rapidly approaching the Polish-German border. We were totally unaware of this, and the only thing that we became aware of was that at three o'clock one morning the Germans moved in and roused us from our beds, told us to dress, bring what we could with us and that we were leaving the camp. They did not give us any chance to organize any form of resistance or any plans to hold up on marching or any other form of thing. We were completely ignorant of the military situation. After much standing around and hollering and shouting, we finally left the camp about 5:00 a.m. and this was, to my knowledge, about January 15, 1945. VI. March to Cross the Oder River As I have said, we tried to keep ourselves in reasonably good physical condition; however, we were not prepared to face the rigors of an eastern winter and we certainly were not clothed for it. We now know that the German plan was to force-march us to cross the Oder River so that we would be behind their new planned line of defence. The attempt to force-march men who were not equipped - through blizzards, without proper footwear, without food - was insane; however, under the press of their rifles we marched on. The second threat which forced us on was the fact that the SS were mopping up in the rear and we had reason to suspect that a lot of the POW's who could not any longer walk were done away with by this mop-up crew. These people had no scruples. It is impossible to describe the hardships because you become sort of numb, things do not register, days run into one another, and you are cold, hungry and you don't give a damn. Occasionally the Germans found shelter for us in barns and this gave us another problem. Cattle were being fed sugar beets - the sugar beets had been stored in the fall and the tops had begun to go bad but, in their great hunger, these were eaten by everyone, including myself. The resultant dysentery further weakened us and left us in terrible condition to continue the march. However, we were forced on until we had crossed the Oder and had gone several miles beyond, to a railhead, the name of which I have forgotten but I believe it was Goldenberg. Because of the condition of the men and their being unable to move further, the Germans then decided to throw us on board cattle trains, to try and move us further west. VII. Train Journey by Boxcar We were loaded sixty men into boxcars, or cattle cars, which were meant for ten horses or forty men. This meant that there was not enough room for everybody to lay down or to sit and, as a result, we worked in shifts on standing while others lay and others sat. Ventilation was provided by two small windows in the upper part of the car. As I have related, nearly everyone had dysentery, including myself. The Germans would not provide a latrine in the cars nor would they allow us out of the cars to be able to help ourselves. The horror and nightmare of this period will long be remembered by anybody who had any part of it. By this time we were so weakened that we had very little control over ourselves. As I recall it during this period, there was no food made available to us and we had no Red Cross food left. We, therefore, existed on some water that they occasionally brought to us but otherwise we remained for hours and hours on end in sidings waiting for trains,, waiting for engines, or waiting for them to clear the right-of-way from bombing and strafing done by our own aircraft. It was difficult to have them remove the people who had died during this time, but under great argument they finally removed the bodies. In this miserable condition we finally arrived at Stalag III located at Luckenwalde which was southwest of Berlin. The Germans put us through a delousing shower and weighed us. My weight at that time was 124 lbs. (at the time of capture my weight would have been approximately 175 lbs.). We were turned loose into a big barracks with no bunks, and straw on the floor, for which we were extremely grateful. We started with 1700 men from Luft VII, and we arrived with something in the order of 900. The total rations issued by the Germans amounted to one and one-half pounds of margarine, three cups of soup, and three loaves of bread. Now this was to have lasted us a month. The thing that allowed us to survive at all was the amount of Red Cross food that we were able to pack with us out of the camp. VIII. Life at Luckenwalde Luckenwalde was apparently established as a camp for the sick and wounded with the more able shipped to other camps. The move to Luckenwalde was not, however, for the care of the disabled but only to keep them from causing interference to the other men. More men died after we arrived in camp, but we were unable to determine the number because the Germans kept these facts from us. We lay in the dirt and filth on the floor, we were too weak to help ourselves, and there was nobody there to help you. The German rations were extremely low. By this time there was never any meat in the soup, it was generally a cabbage or green leaf soup, and you got a slice of bread, and ersatz tea. We were unable to recover on this. During the time that we were at Luckenwalde, (estimated) from February 24th to April 20th, we received one Red Cross parcel for sixteen men. The warmer weather helped us to some degree, we suffered less from the cold in the latter part of March. We were able to get our clothes and blankets out in the sun which helped us to control the bedbugs, lice and fleas. On April 20, 1945, a Russian armoured car and tank appeared at the camp. By this time the Germans had pulled back and had left one old man as a guard at, the camp. We had been warned by broadcast from London not to leave the camp under any situation. Officially, we were liberated. IX. Life Under the Russians On liberation, our food situation did not improve. In fact, it worsened. For a few days there was nothing to eat at all. Eventually the Russians decided to supply us with some food but they, in turn, were short of rations as it was their practice to live off the land as they passed through German territory. They would not recognize the Italians and Poles and some of the other national groups in the camp, as allies, and only would supply sufficient rations for Americans and British troops. As a result, we had to share and, again, food shortage was ever apparent. A few days later a group of four American newsmen arrived through the hook-up at Wittenberg and were on their way to cover the fall of Berlin. They radioed back to the base and informed the Command of our dire needs and, in particular, those of our wounded and sick, and requested emergency aid in the form of ambulances and doctors to be brought in immediately. The Russians in the meantime more or less ignored us. The American ambulances arrived and in two days were successful in evacuating many of the sick and wounded. The Military Advisor from the American forces came in with the ambulances to try and organize the removal of the remainder of the allied prisoners. The following day a fleet of American transports arrived and the Russians allowed them to load and then, for some reason, surrounded their transports and made everybody dismount. They informed us that they would evacuate us in their own time and it would be through Odessa and back through by Cairo, the Middle East and thence to the U.K. Undoubtedly this was done in order to give them a chance to screen the different people in the camp to see that there were not some political prisoners there that they were interested in. The American Captain in charge of the transport advised that he would pull down the road some eight or nine kilometers and that he would wait until 1:00 a.m. and any person who could make it, he would be very happy to take them back. I, along with a group of four others, decided that we would make the try. At the back of the camp there was a swamp which paralleled the road down which the American transport had gone. We, therefore, tried to walk through the swamp in the dark far enough to get beyond the guards which the Russians had posted. However, we must have made enough noise to sound like a large tank because when we finally cut out to the road we walked into the arms of Russian soldiers. They returned us to the camp and informed us that they were going to throw us in the brig but after some negotiation with a couple of cigarettes we were successful in having them return us to our barracks. We decided that we must get out and that we would make another run at it about 4:00 in the morning. This time we walked in the swamp until noon, paralleling the road, and cut out to the road beyond the outer ring of Russian guards. At the time there were thousands of refugees on the road trying to make their way back west and to the Allied Armies. By mingling with them we were able to hide our identity. We made for Wittenberg. When the Americans had reached the Elbe, they had bridged the river and established a small bridgehead on the east side of the river. We contacted the American soldiers in this bridgehead and they provided us with transport across the river to a place called Schonebeck, which was an evacuation centre for POW's. By this time thousands of prisoners were arriving by various means and it seemed to us that the evacuation was going to be a slow process. After three days of good food and rest we decided that we would continue on hitch-hiking across Germany and make our way back to England ourselves. We eventually arrived at a city called Osnabruck. Here, a Colonel in charge of American Transport informed us that the R. A.F. were just completing their evacuation of POWs out of Hildesheim, but he knew there were two aircraft coming in the following day to pick up the spare parts they had stored there. He felt sure that he could get us on these aircraft and so we took the offer of transport to Hildesheim and were successful in getting a ride back to England. |

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed