|

Found these amazing photos. The first is from 1911. The two people in the front seat of the wagon are Charlie Davis and Emily Campbell, my great grandparents. The woman in the back seat is Olive Dunning, Emily's sister, with her son, Robert Dearle Dunning, age 5. Although the caption with the picture didn't state it, the baby in front probably my grand uncle, Peter Charles Davis. The building behind them might be their livery? This second photo is from 1931; a picture of the Birch Hills High School softball team..My Grandma, Grace Davis, is the back left.Her sister, Emma Davis, is in the front middle and her cousin, Emma Dunning, is front right. These photos are not the best quality, unfortunately. I plan on contacting the society who has them in their local history to see if they have the originals. Any of my Simpson family know who might have copies?

For a North American family, history means movement. Some families crossed the ocean and settled on the coast. However, our families were mostly farmers, so they were continually pursuing land for themselves and their children. These ancestors would settle newly opened lands, but when those lands filled up and there was little land for their sons and daughters, they would pick up and move west again.

Grace Davis, my paternal grandmother, was half Scottish, on her mother’s side. Her maternal great-grandparents were probably born in Perthshire, Scotland, over 7,500 kilometres from where her mother, Emily Campbell, was born. Both her great-grandparents and her grandparents undertook treacherous journeys that not only crossed tremendous distances but removed them from family and friends into harsh, lonely new environments.

John Duncan Campbell was born in Scotland about 1810 and migrated to Canada early in the 19th century. Unfortunately, John Campbell is an all too common name, and censuses did not begin in Scotland until 1841 and in Upper Canada until 1851, so it's challenging to determine exactly where in Scotland he was born. However, since he ended up in Lanark County, Ontario, an early destination of many Scots from Perthshire, he may have been born in that Scottish highland region.

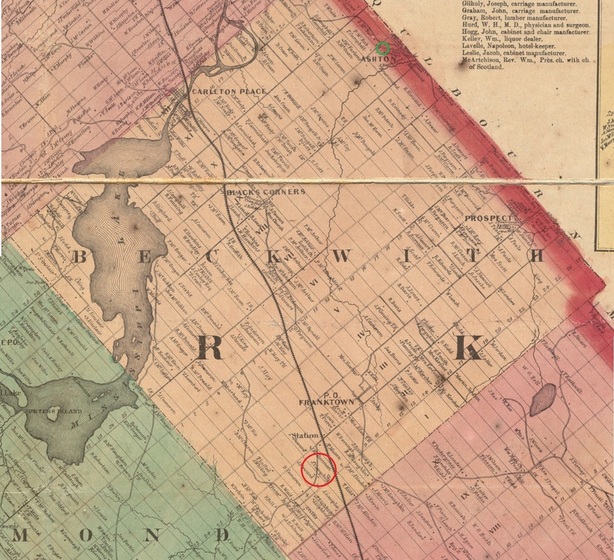

According to "A Pioneer History of the County of Lanark" by Jean McGill, in the late 18th century, Lanark County, which lies about 60 kilometres west of Ottawa, was heavily forested and sparsely populated except by natives and bears. United Empire Loyalists initially settled the region after the American Revolution, but the soil was rocky and poor. In 1816, surveyors completed their mapping a portion of Lanark, named Beckwith Township after the Quartermaster General of Canada. Soon, settlers built a road through the region and laid up an ample provision store at Franktown. Into this new township settled several hundred Scots from Perthshire, Scotland. On an 1863 map, John Campbell's farm was only a few kilometres south of Franktown, making it likely that his family were early settlers into the area.

Originally, these Scots spoke Gaelic, until subsequent Irish and English migration changed the common tongue to English, and worked the land with sickles and scythes, primitive plows pulled by oxen, and home-made, heavy iron rakes. The Scots worked morning until night, logging trees, burning brush, planting and reaping. Women worked in the fields with men during the day, their young children swaddled nearby. After dark, the women cooked dinner, put the children to bed and mended their family’s threadbare clothing while the men finished up the work in the fields.

Elizabeth McNaughton was born in 1816 and baptised in Fortingall, Perthshire, Scotland to Duncan McNaughton and Catherine McGregor. By 1841, Elizabeth's father had died and most of her siblings had married and moved on, leaving only herself and her younger brother, James, to care for her 60 year old mother. That same year, the three decided to board a ship for Canada. Their passage across the Atlantic was likely in a small wooden sailing ship, where they were crammed into an overcrowded hold for 8 to 12 weeks. Even the smoothest passage had a few deaths, while a particularly poor trip might result in dozens of fatalities from disease and malnutrition. Happily, the small family endured their voyage across the Atlantic and up the St. Lawrence Seaway, to eventually arrive in Lanark County, Ontario. Soon after arriving, Elizabeth met John Campbell and they married a year later, on September 30, 1842. It's not known whether John had his own farm at this time or whether they obtained it later, but they set up their home and Elizabeth's mother moved in with them. They had their first child, Catren Campbell in 1843, followed by Margaret, Duncan, Peter, Donald, James, John, and Elizabeth Ann. Duncan McGregor had been born on April 24, 1828, likely in the village of Dull, to Robert McGregor and Elizabeth McGibbon and baptised the same day on at the nearby parish church in Fortingall, Perthshire, Scotland. Within the churchyard is the Fortingall Yew, an ancient tree estimated to be between 3,000 and 6,000 years old. Robert was an innkeeper in Dull and also worked as a miller, which may have explained how Duncan picked up his trade. By the age of 21, Duncan had completed his apprenticeship, becoming a journeyman carpenter, and set off to work in communities around Perthshire. Amelia Forbes was born in 1835 to Charles Forbes and Helen Fergusson in the parish of Moulin, Perthshire. Charles was a gardener his entire life and it's possible that he was one of the many gardeners who worked at Dirnanean House, the ancestral home of the Small family, a sept of Clan Murray.

The Forbes family had lived in Moulin since at least 1700 and its possible that they may have been in service to the Smalls for generations.

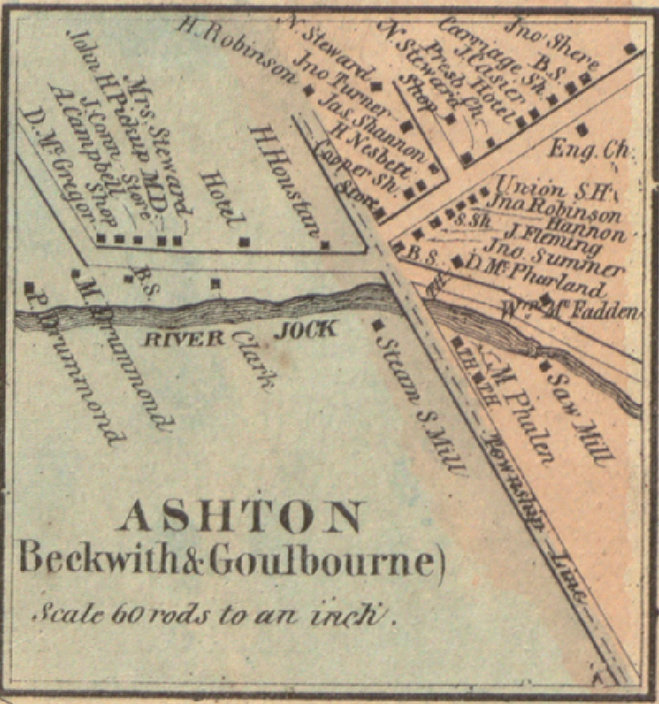

Helen Fergusson died when Amelia was a young teenager and some of her younger siblings went to live in the homes of her older siblings, with only herself and her youngest sibling, Christian, remaining with her father. Amelia worked as a dressmaker as well as looked after her father and sister. Possibly working around Enochdhu or Dirnanean House, Duncan met Amelia and a romance began. On January 16, 1855, they married in Moulin. With her sister now 16 and her father still healthy and working as a gardener, Duncan and Amelia departed Scotland forever. As with so many other immigrants, the Newlyweds made the long, dangerous passage across the Atlantic to Canada, and to Beckwith Township in Lanark County. They ultimately settled in the small village of Ashton, which was a hub of industry in the county, home to merchants, blacksmiths, weavers, labourers and at least one new carpenter. Most of their fellow neighbors were fellow Scots, with names such as Kilpatrick, Campbell, Stewart, McEwan, McCrusty, Robertson, and.Carmichael,

Duncan and Amelia were prosperous and their family grew quickly. They had their first child, Emma Jane, in 1858, followed by seven more children: Charles Forbes, Duncan, Nellie, Robena, Kate, Alexena, and Adele, the youngest, who was born in 1875.

With the McGregors in Ashton and the Campbells south of Franktown, future husband and wife, Peter and Emma, lived about 16 kilometers apart from each other. It's not certain how the couple would have met but given their similar background, culture, and religion, they likely had many opportunities at church or social events. Also, with so much construction in the township, with new mills, homes, and barns continually being built, Duncan McGregor’s carpentry trade likely had him working far and wide. Scottish culture in Lanark was devoutly Presbyterian and very literate. Families regularly read their bibles but often had libraries made up of weighty classics, such as “Gibbon’s Roman Empire”, and “D'Aubigne’s History of the Reformation.” Both Peter and Emma would have attended school. According to McGill, the teachers were no-nonsense disciplinarians, who never hesitated to use the strap on students, or even a horse whip on occasion. The students were drilled in geography, grammar, reading, spelling, and arithmetic. Likely because of the Scottish emphasis on education, children went to school until they were adults so children generally received very good educations

On April 5, 1880, standing beneath the vaulted ceiling of the Methodist Church in Smiths Falls, Ontario, the grey-haired Reverend George H. Davis married together 28 year old Peter Campbell and 22 year old Emma Jane McGregor.

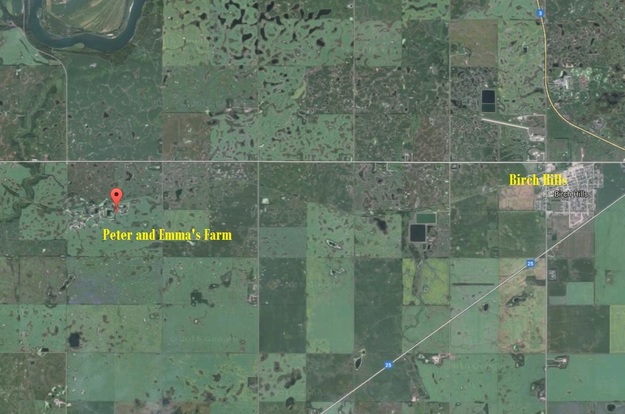

Until his marriage, Peter had farmed with his father and brothers. However, his oldest brother, Duncan, had also recently married and his wife, Bella, had moved in family. Additionally, she very soon gave birth to a daughter. If the already crowded family home did not motivate Peter and Emma to strike out on their own, the first few weeks of night feedings certainly would have. Fortunately, they had before them a tremendous opportunity. In 1872, Canada had passed the Dominion Lands Act, which provided almost free homesteads to anyone willing to settle on the remote Canadian prairies. However, despite the act, land was only slowly becoming available, dependent on the completion of surveys of the vast territory and negotiating treaties with the First Nations peoples. Following the French and Indian War, in 1763, King George III of Great Britain had issued a Royal Proclamation that forbade all settlement in western territories. This Proclamation was not intended to prevent all westward European expansion but to merely prevent private purchases of First Nations land by colonial settlers. The Crown intended to manage all future land purchases from the First Nations so that settlement could occur in a more orderly fashion. In 1871, the Canadian government negotiated theirfirst treaty with 7 nations in Manitoba. In the next several years, they would negotiate 6 more treaties with several dozen more nations, encompassing almost all the lands today in northern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. The First Nations peoples often were not happy to negotiate away their territory but many felt pressured the disappearing buffalo and the devastating cholera and smallpox epidemics. The Crown guaranteed the remaining land and promised to deliver education, economic assistance, and famine and pestilence relief. In return, these First Nations surrendered their ownership over most of the vast Canadian west. Up until 1881, only 60 homesteads had been granted to settlers in the Saskatchewan territory. However, with the surveying complete and the treaties negotiated, the floodgates were soon to open and Peter and Emma intended to be there. Starting out in 1881, Peter and Emma said goodbye their families and boarded the train for a 1,800 kilometer trip to Saint Paul, Minnesota. Once there, they joined a wagon train, driving a team of oxen across 1,500 kilometers of prairie to Prince Albert. Along the journey, or shortly after, Emma gave birth to their first child, John Duncan Lorne Campbell. On July 5, 1882, Peter Campbell and Emma Jane McGregor paid a $10 filing fee and registered a homestead claim for a quarter-section, 160 acres, of land in Section 22, Township 46, Range 25, and Meridian W2. The quarter-section lies about 8 kilometers straight west from Birch Hills. To keep ownership of their homestead, Peter and Emma had to live there and clear and cultivate 40 acres over the next 3 years.

Since there was timber in northern Saskatchewan, Peter and Emma could likely construct a real house, not having to rely on the infamous sod houses of southern Saskatchewan. They also managed to purchase cows, chickens, and pigs. During these years, they added to their family. In 1883, Emma gave birth to Charles Forbes Campbell, followed by Olive in 1885, Peter Howard Russell in 1886, Arthur in 1889, Emily Robena Elizabeth in 1891, and Myrtle Alexina in 1895.

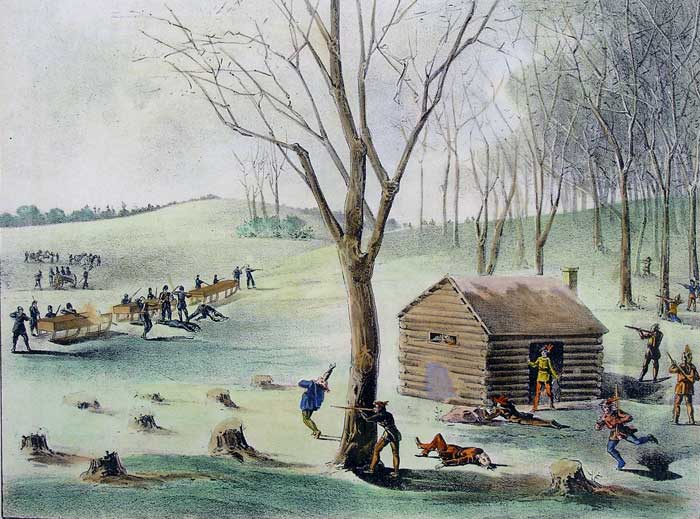

Also, sometime in the 1880s, Emma’s parents and siblings joined them in the Prince Albert area. A few years after arriving, all Emma’s brothers and sisters soon married, usually to fellow Scots, and raised families in the area. Her sister Nellie married later in life, in her mid-thirties, around 1900. Tragically, she died 3 days after giving birth to her only child, Graham McGregor Neilson. Emma’s sister, Graham’s Aunt, Alexina McGregor Wright, raised the boy. These would have been very hard years for the Campbell’s. Not only did they have a prodigious amount of work before them, to carve out a profitable farm while raising a growing family, but there was tremendous unrest in the region as well. With the disappearance of the fur trade and the bison, First Nations and Métis had lost much of their former livelihoods. Moreover, the crops of 1883 and 1884 were very poor, which created hardships for everyone in the region, native and settler alike. Unsurprisingly, the Canadian government was too distant and aloof to respond to these hardships and many native groups became very determined to press for change. Many natives and Métis gathered together and invited Louis Riel back to Canada. With Riel, they soon wrote a Revolutionary Bill of Rights and sent it to the government; an act which began the rebellion. Despite a great deal of anti-government rhetoric among white settlers before the 1885 rebellion, none of them joined it, choosing to loyally support the Crown. According to Peter and Emma’s grandson, Olive Campbell’s son, Robert Dearle Dunning, sometime in March, an armed detachment of North West Mounted Police escorted the Campbell’s and their neighbours north to Prince Albert, where they were housed in a fort built of cordwood. Soon after, 100 mounted police and armed civilian volunteers moved southwest from Prince Albert towards the Town of Duck Lake, where Louis Riel and the rebels were encamped. According to accounts, Peter had volunteered to help as a transport driver but I'm not sure if he was part of this expedition. Negotiations between the two groups went badly and a 90 minute battle began. After 12 deaths among the police and volunteers and six rebel deaths, the police and volunteers withdrew back to Prince Albert. Mercifully, Riel chose not to pursue them.

The Canadian army soon arrived in the region, with trains bringing more soldiers every day. It soon became clear that the rebels would not mount an attack against Prince Albert so the Campbell’s and their neighbours were permitted to return to their farm. According to Dunning, they found that all their poultry, pigs, and cattle had been slaughtered by the army for provisions. It would be some time before they were compensated for their loss.

After a few months, the army finally defeated the rebels and captured most of its leaders. Their trials were held that fall in Regina and its likely Peter and Emma followed it with great interest. Riel was hanged on November 16. It’s likely that Peter would have approved. Despite these difficulties, Peter and Emma were officially granted their homestead on October 30, 1888. Tragedy struck the family on October 14, 1895, when their oldest son, who went by the name Lorne, died of “Inflammation”. This is an archaic medical term and could indicate many conditions, ranging from appendicitis to pleurisy. The local article mourning his death described Lorne as “a bright and promising boy of fourteen years, and was highly thought of by all who knew him.” The Campbell’s lived less eventful lives for the next many years, with the typical tragedies and celebrations. Emma’s father passed away on April 10, 1903, at the age of 73. Two years later, in 1905, their daughter, Olive, married Robert Dunning, a member of the North West Mounted Police. Robert and Olive moved to North Portal for a few years but they eventually returned to the area and farmed north of Birch Hills. In 1909, Emily married Charlie Davis and lived in Prince Albert, Shellbrook, and then they too moved back to Birch Hills. Their 3rd child, Grace, was my grandmother. Emma’s mother, Amelia Forbes, passed away on June 8, 1913, at the age of 78. The boys, Forbes, Howard, and Arthur lived on the farm until 1916. About 1919, Forbes married Lillian Barr, and established his own farm. Forbes and Lillian had at least 3 sons, Charles, Leslie, and Gordon, who all served in World War II. Arthur married Laura Stevenson and also farmed. He had at least 2 sons: Arnold and Clayton. Howard remained on the farm, possibly taking it over from his parents. I have small newspaper excerpts of Emma visiting Emily for week long visits in Shellbrook, so the family appears to have remained close, even when geographically distant. Peter and Emma remained on their farm until his death in 1928, at the age of about 77. Emma died in Prince Albert in 1935, also about the age of 77. Ultimately, Saskatchewan was one of the last lands open for new settlement that offered inexpensive homesteads so, finally, their children eventually had to abandon farming and make another big move into the towns and cities. However, the success of their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents in farming, as well as a strong appreciation of hard work and education, ensured that their descendants prospered. |

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed