|

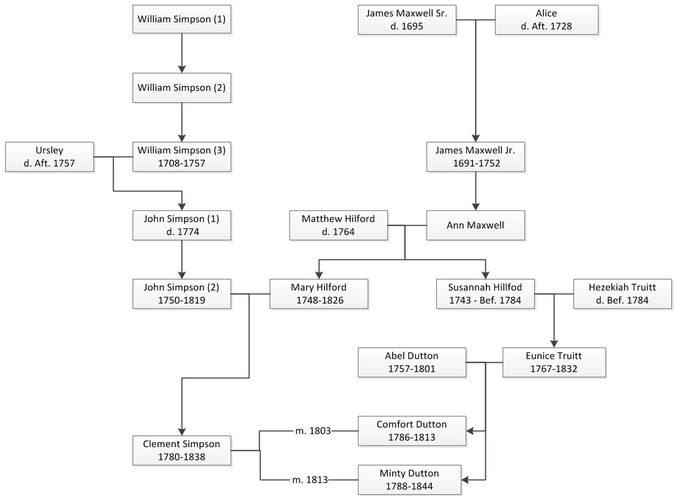

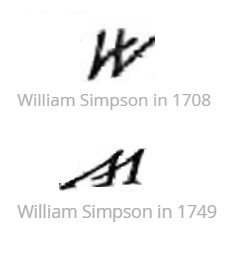

When word of the Declaration of Independence reached their farm on the Mispillion Creek, John and Mary Simpson may have greeted the news with trepidation. Declared on Thursday, it's unlikely that the published text reached them quickly. Philadelphia newspapers printed the Declaration on July 4th and July 6th, but copies would have required a few days to travel the 100 miles south to the middle of Delaware. John and Mary might have journeyed into Milford, a bustling town of sawmills and shipbuilders, on Sunday, July 14th, to attend church and had heard the declaration pronounced from the pulpit. However, as they looked about at their fellow parishioners, they may have seen as many furrowed brows as exuberant cheers. Although Delawareans shared most of the Declaration's grievances, they had been largely content with their government, and they were acutely aware of the hardships that a rebellion would bring. However, with the drums of war beating for months, there was a sense of inevitability. Ministers railed against Parliament from the pulpit, neighbours seized guns and powder, and separatists had announced independence from Britain and their Penn family proprietors. In response, the British would send a 44-gun frigate to patrol the Delaware Bay, interdicting Delawarean shipping [1]. However, whether they were fervent patriots or still on the fence, the toil of daily living did not stop because of war; it only grew more challenging. Everyone still had to eat. Twenty-six-year-old John and 28-year-old Mary planted wheat, Indian corn, and beans [2], much of which ended up in Philadelphia or Baltimore, especially with the cessation of trade with Britain. They might have hired hands or rented a slave from a nearby farmer during the busy harvest season. However, it's just as likely that family and neighbours pitched in, as John and Mary would assist them in return. The Simpsons kept sheep, cows, chickens, and hogs [4] and produced most of their household goods themselves [5]. Mary spun wool into cloth, sewed clothing, picked apples to press into cider, cooked, baked, and used their used cooking fat and lye skimmed from boiled ashes to make soap. She would need a whole day to launder their clothes, a task which required hauling water, chopping wood to boil the water, and beating and hanging the clothing [6]. John gathered and beat the flax that grew near the river so Mary could spin it into thread. He also built fences, cleared trees, butchered hogs, cure hides, crafted boots, and forged farm implements. There was rarely a moment, outside of worship, when both were not hard at work [7]. Mary was born to Matthew Hilford and Anna Maxwell of Kent County on July 15th, 1748 [8]. There is no record of where Matthew was born; he may have been born in British America or arrived from England as a young man [9]. Anna Maxwell was the daughter of James Maxwell Jr. [10], who worked as a joiner [11], and the granddaughter of James Maxwell Sr. and Alice Adams [12]. James Sr. and Alice, both widows, were married in Dover, Delaware, on May 2nd, 1688 [13]. James Sr thought to have immigrated from Scotland, possibly transported to America as a captured rebel, ran an ordinary, or tavern, which served as the home to county court for a time [14]. Matthew and Anna had a large family, with two sons and seven daughters surviving to adulthood. Sadly, Matthew died in 1764, when most of his children, including Mary, were still minors. Matthew divided his estate among all his children, leaving the land to his sons and money to his daughters [15]. Living near the water in the warm, humid Chesapeake climate caused many to perish from typhoid and yellow fever at a young age. In the next few years [16], Mary soon lost more family, including her mother and a brother, leaving her an orphan in her early twenties, which was typical for this time and place. Three-quarters of all children around the Chesapeake would lose a parent by the time they were 21, and one-third of all children would lose both parents [17]. John Simpson Jr. was born December 28th, 1750, on his father's plantation in the Mispillion Hundred of Kent County, or Milford Hundred as it's known today [18]. The Simpsons had lived in the county for generations. On April 13th, 1674, the Duke of York had issued a patent to William Simpson for 400 acres in St. Jones County, Delaware [19], which would become Kent County after the colony transferred to the proprietorship of William Penn in 1682. The tract of land known as "Simpson's Choice" sat next to the future village of Little Creek Landing, the home of a thriving oyster industry [20]. Many generations later, a history book described the Simpsons as Scotch-Irish, a label given to many Scottish, Scotch-Irish, and northern English settlers because of their common manner of speech and folkways [22]. William Simpson may have originally migrated to the eastern shore to Maryland and then travelled north seeking better opportunities. 1674: Duke of York grants William Simpson (1) 400 acres at present day Little Creek Landing 1701-1711: William Simpson (2) mentioned in multiple land sales as a neighbour near Little Creek Landing 1718: William Simpson (2) leases 200 acres in Kent County for annual rent of 16 shillings, 8 pence 1732: William Simpson (2) purchases 120 acres north of Pemberton's Branch, near Milton, Broadkiln Hundred 1749: William Simpson (3) gifts 147 acres to his son, John (1), on the south side of Mispillion Creek 1771: John Simpson (1) divides 2 tracts of land, Mount Pleasant and Simpson's Folly, totalling 67 acres to be given to his sons, John (2). and Robert 1787: John Simpson (2). purchases 43.5 acres for 30 pounds from his brother, Robert, on the south side of Mispillion Creek, south of Beaver Dam road, which is today in South Milford 1791: John Simpson (2) sells 112 acres, includes parts of the tracts knowns as Simpson's Crossroads and Mount Pleasant, for 224 pounds William (1), and then his son and namesake, William (2), owned property on Little Creek until at least 1711, where a land sale document mentioned them as neighbours [23]. They possibly grew tobacco, a typical cash crop of this time and place, which would have required them to employ indentured servants or even slaves. There was very little currency in the colony, so that William would have purchased everything, from indentures to household goods, with barrels of tobacco. Almost all goods would have come directly from England, as colonists manufactured very little domestically. There is no record of William or any of his descendants owning slaves, possibly because if he did farm tobacco, a very labour-intensive crop, he likely soon switched to wheat and corn. Also, unlike plantations in the southern colonies, where often the eldest son inherited the whole of the plantation, Delawareans usually divided their inheritance among all their children, both sons and daughters, resulting in smaller farms over time. In addition to the decreasing economic value of slavery, ministers stridently denounced the peculiar institution from the pulpit. Further, with the American Revolution, Delawareans found themselves fighting for a principle that all men were created equal. Farmers in Delaware began voluntarily freeing their slaves faster than anywhere in the United States. At the beginning of the Revolutionary War, 95% of Delaware's two-thousand African-Americans were slaves, falling to 70% in 1790 and 24% by 1810. However, unlike the northern states, Delaware never did abolish slavery before the Civil War; in 1860, 8% of its African-American population were still in bondage [24]. There may have been only a few Native Americans in this part of Delaware at William Simpson's arrival. As with many indigenous nations, the Lenape had been devastated by diseases such as smallpox and measles. Additionally, their vigorous trade with the Dutch had sparked a war with their better-armed rivals, the Susquehannocks, and they lost much of their southern territory and moved west to Ohio. Predictably, as the Lenape moved west, settlers quickly moved to occupy their lands [25]. In 1708, William Simpson (2). put his mark on the last Will and Testament of Luke Manlove, who owned land on the north side of Mispillion Creek, less than 20 miles south of Little Creek, the first record of a Simpson in the Mispillion Hundred [26]. In 1732, William Simpson (2) purchased 120 acres near Milton in Sussex County, Delaware from Jane Blare. This land deed was witnessed by Mark Manlove, a co-witness on Luke Manlove's 1708 Will and Testament, suggesting this is the same William Simpson and that possibly these two families had close ties [27]. Although this is pure speculation, since I have several genetic cousins descended from this Manlove family, there is a possibility that William (1) or William (2) had married a Manlove. The mark of William (2) bears a close resemblance to the mark of his son, the next William Simpson (3). Most people writing a mark drew a simple X but these two William Simpsons had a more complex creation [28]. Beyond their proximity to each other in Kent County and a lack of other possible Simpson descendants in the region, the similarity of their marks are the strongest evidence that William (2) and William (3) were father and son. William Simpson (3) and his wife, Ursely, settled on plantation south of the Mispillion River, near Milford. A land indenture described the property as located in the Mispillion Forest, a vast woods of oak and pine, which meant that before William could farm, he needed to clear the land. If William was a typical farmer, he could clear an acre or two every year, meaning it might have taken him his lifetime to clear his farm. He would strip the bark from a narrow band around a tree, which would kill it over the next year. As leaves would no longer grow on the tree, he would simply plant around it at first. Eventually, William would cut or burn the tree, leaving the stump, which he might never extract since it was rarely worth the effort [29]. William and Ursley had six children survived to adulthood. Their oldest son, William (4), died in 1747, leaving them with 2 remaining sons, John (1). my 5x great grandfather, and Moses and three daughters, Jane, Elizabeth, and Jamina [30]. A DNA test on the Y-chromosome of myself and a direct male descendant of Moses Simpson prove beyond any doubt that William Simpson (3) is our ancestor. In 1749, William granted John (1) 147 acres on the south bank of the Mispillion River, very close to South Milford [31]. John (1) had only three children survive to adulthood: John (2), who was my 4x great grandfather, Robert, and Mary [32]. John (1) was a widower when he died in 1772, meaning that John (2) was also left orphan in his early twenties. John Simpson (2) and Mary Hilford were married shortly before 1772 and had at least one surviving child in 1776. The Simpson and Hilford families had been friends and neighbours for decades [33]. Over the next few years, John and Mary would have several children: Nancy in 1773, Esther in 1777, Clement in 1779, John (3) in 1781, and Thomas in 1783 [34]. Not surprisingly, the Revolutionary War piled hardships on the people of Kent and Sussex counties. The state levied new taxes, patriot and loyalist militias seized produce, and a 1780 drought devastated the wheat crop. When the British fleets sailed up the Chesapeake in 1777 and captured Philadelphia, the Simpsons and their neighbors would not have only been increasingly worried about British raids but they also lost access to Philadelphia and Baltimore markets for over a year [35]. While the majority of Delawareans in 1776 were likely lukewarm about independence, sentiments gradually moved towards a thirst of independence, influenced by constant stream of pamphlets and sermons extolling the virtues and principles of the revolution as well as the embellished stories of British atrocities. Still, Delaware was very divided between those who supported independence, called Whigs, and those loyal to King, called Tories. Over the next few years, Tories and Whigs waged a low level war, intimidating and assaulting each other. Tories attacked shipping and raided Whig homes. The dominant Whigs confiscated and auctioned off Tory property. The Delaware Assembly responded to Tory resistance by requiring all white men over 21 to sign an oath of allegiance or be considered disloyal and lose their franchise to vote, hold office, and serve on juries. In 1778, John Simpson signed this oath to “protect and maintain independence and constitution against secret and traitorous conspiracies” [36]. Since ardent Tories refused to sign this pledge, it's likely that John and Mary had come to support independence, if they had not supported it from the beginning. In 1780, after the British had seized Charleston, North Carolina, William Dutton and Boaz Manlove, member of families close to the Simpsons, helped to organize pro-British armed camps in the Cedar Creek Hundred hoping to secure the county for the British. However, the effort was poorly managed and the Delaware militia quickly captured or dispersed them [37]. After the war, most Tories did not quit Delaware, although many of their neighbours vigorously encouraged them to leave. In 1790, Delaware dropped the requirement to sign an oath of allegiance and the Tories regained their franchise [38]. Judging by the politics of their sons, John and Mary may have been Federalists, the party of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams. This party stood for a strong central government, a central bank, a national navy, and international neutrality. In contrast, the Thomas Jefferson Republicans fought for states rights, decentralization, and were close to revolutionary France [39]. Mary’s older sister, Susannah Hilford, died along with her husband, Hezekiah Truitt, sometime before the end of the Revolutionary War, leaving behind at least 2 orphaned daughters, Tranny and Eunice [40]. There is some evidence that John and Mary helped care for their nieces. Eunice married Abel Dutton of Cedar Creek Hundred in about 1785 and they settled near Milton, 12 miles south of the Simpson farm. Their first four children were girls, Comfort, Minty, Susannah, and Priscilla, followed by three boys, Hezekiah Truitt, Abel, and John Simpson. That they had explicitly named their third son after John suggests a very close relationship between the families [41]. In July, 1796, John and Mary sued her nephew, Robert Hilford, the son of her oldest sibling, Thomas. Matthew had left the residual of his estate to his six daughters. However, in 1777, Thomas declared to the Orphan Court that some of the residual was maintained in an administration account, amounting to 61 pounds and 3 pence. Thomas never distributed this sum to his sisters and, when he died in 1790, the administration passed to his son. Mary and her two surviving sisters, who filed their own suits, each sued Robert for 1/3 of the remaining residual. Unhappily for them, the Court refused the lawsuits, ruling that Thomas's declaration was not an implied promise to his sisters to pay out the administration account [42]. About this time, John and Mary's oldest daughter, Nancy, perished in an accident. Despite the loss of so many family already, the sudden loss of a child must have been devastating [43]. In 1801, Abel Dutton weak and ill for many months, died, widowing Eunice and orphaning seven young children, the oldest 15 year old Comfort, the youngest, less than a year old, John Simpson Dutton. Fortunately, Abel left his family a good inheritance to provide them some income [44]. In 1804, John and Mary’s oldest son, Clement, 25 years old, my 3x great grandfather, married Abel and Eunice’s oldest daughter, Comfort, who was 18 [45]. The newlyweds were first cousins, once removed but cousin marriages were common at this time and the nuptials likely would have not provoked objections. At this time, we have the first hint of the religious faith of the family. Being of Scottish descent, we could guess that the Simpsons were Presbyterians, especially since that faith had a strong presence in religiously tolerant Delaware [46]. Abel and Eunice, however, were Evangelical Methodists. At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, 31 year old Francis Asbury was one of only two Methodist ministers in the United States. Americans had become hostile towards the the new faith, which was a denomination of the Anglican Church so from 1777 to 1780, Asbury found shelter in Kent County. Immediately after tensions diminished, he began an historic mission, riding all over the United States, preaching daily sermons, growing the faith from 1,200 to 214,000 members [47]. In the next few years, many in Kent County, including families near the Simpsons, converted to Methodism. During this period, Methodists held their services outdoors or in people’s homes, possibly including the home of Abel and Eunice. At the time of his death, Abel was also on a committee to construct a church in Milton, a church that still exists today [48] . Although Methodism would later schism over the issue decades later, at this time the faith was strongly opposed to slavery, held mixed-race services, and had free black ministers who preached to white audiences. Abel and Eunice, however, owned at least two slaves, which must have conflicted them [49]. Abel freed his slaves, manumitting his last one, Hannibal, in his will, which he made shortly before his death in December of 1801 [50]. Hannibal Dutton settled down nearby in the Cedar Creek Hundred, married and had children [51]. Sadly, the end of slavery did not mean complete freedom and the African-American population in Delaware remained oppressed under the “Black Laws” for a long time to come. There is no direct evidence that John and Mary became Methodists but their youngest son, Thomas, would name one of his children Silas Asbury Simpson [52], suggesting he had adopted the faith. Further, when Clement Simpson's great grandson, Lowell Simpson, crossed the border into Canada, he would state his faith as Methodist [53]. In 1805, Thomas Simpson married Mary Cecil from Maryland and farmed a tract of land near his father and brothers. He farmed in the Mispillion Hundred for the rest of his life, dying in 1829, after being elected to Congress on the John Quincy Adams ticket [54]. With the Federalists firmly against the War of 1812 and with memories of the hardships of the revolution in mind, John and Mary may have been less than enthusiastic about the conflict. Further, in April, 1813, reports of a British landing at the mouth of the Mispillion Creek must have sparked panic in the area. Fortunately, the 150 redcoats stayed only briefly, disappearing with 14 head of cattle and two liberated slaves [55]. While Clement Simpson did serve in the militia in the years prior to 1812, being fined $1 for being delinquent in 1809, there is no evidence that he fought in the war. Clement had fallen on hard times. Comfort died prior to 1813 [56] and he appears to have lost some children to illness or accident. After the death of his wife, he was involved in a lawsuit involving his relationship with a still married woman [57], which may have been somewhat humiliating. However, at the end of 1813, life must have begun to look better to him. Clement married Minty Dutton, Comfort's younger sister and my 3x great grandmother, and they quickly added two children to their family: Thomas and Emory. Then, in 1818, Clement and his brother, John (3), led their families decided west to Ohio. Clement and Minty settled in Harrison Township in Pickaway County, where Clement and Minty had several more children: Comfort, Mary, Nelson, Amelia, and Nancy [58]. Nelson was my 2x great grandfather. Soon after Clement and John left Delaware, their father died at the age of 69 and Mary went to live with her son, Thomas. Mary herself passed away seven years later, in 1826, at the age of 78 [59], survived by four children and at least ten grandchildren. Although John and Mary still have some descendants in Delaware, most live across the United States and Canada.

|

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed