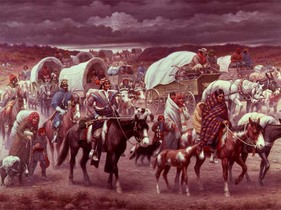

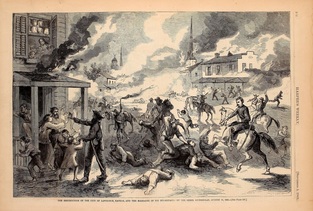

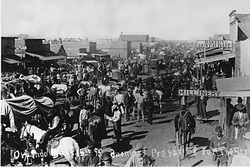

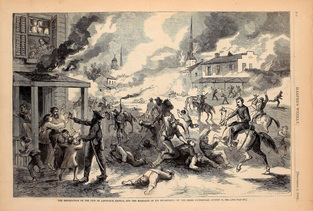

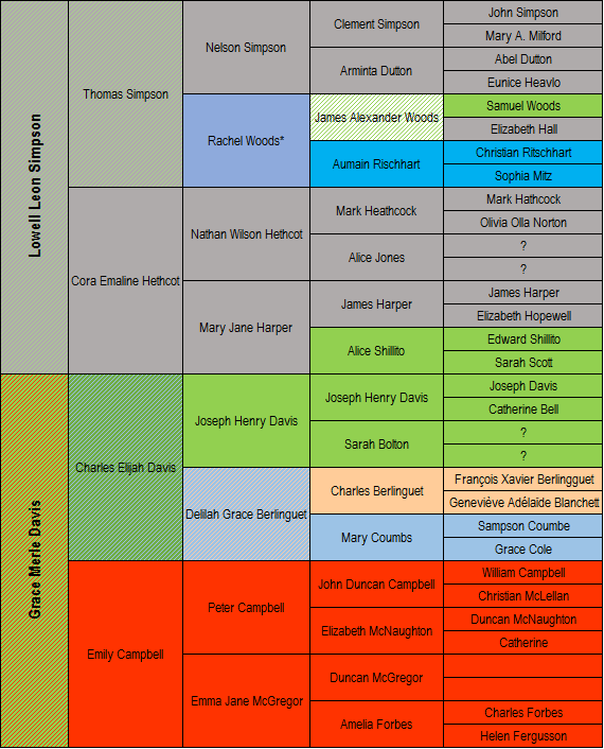

Levi Ferguson and Mahala Mitchell ~1870 Levi Ferguson and Mahala Mitchell ~1870 Rhea (pronounced “Ray”) County, Tennessee, is a rolling stretch of farmland and lush forest nestled between the Tennessee River to the east and the Walden Ridge to the west. My wife's 3x great-grandfather, Levi Ferguson was born here in 1826 and joined the growing family of Robert Ferguson and Rachel Falls. Between 1810 and 1820, the large, extended Ferguson and Falls families, along with several others, had moved en mass from Lincoln County, North Carolina to Rhea County, Tennessee, where Levi, his siblings and many cousins were born between 1819 and 1829. However, around 1830 most of this large clan picked up stakes again and migrated west to Johnson County, Missouri. Some remained behind, though, including Robert and Rachel and their children. Rachel Collins, my wife's 3x great-grandmother, was born about 1829, also in Tennessee, possibly in Rhea County.. There were several Collins families in and around Rhea County in 1830 and 1840 but there is no evidence yet that strongly suggests which family may have been Rachel’s. Rhea County was on the periphery of the deep south and many of its citizens owned slaves. Looking carefully through the census records and slave schedules, Levi had at least one uncle who owned slaves but neither he nor his father did. Of course, there is no evidence at this time that they were opposed to the peculiar institution. It may have simply been that the Ferguson family was poor and slaves were expensive. However, slavery decreased the value of free labour, which hurt poor whites, forcing many to leave the south for the west, where they hoped to obtain cheap land.  Trail of Tears by Robert Lindneux Trail of Tears by Robert Lindneux Slavery was not the only cruelty my wife's ancestors may have witnessed. When Levi was 12 and Rachel was 8, U.S. soldiers escorted bands of several hundred Native Americans through Rhea County on the beginning their journey out west, along the infamous “Trail of Tears”. Both children may have seen Cherokee migrating up the Tennessee River for the last several years, under the orders of the federal government but, beginning in 1838, thousands of Cherokee were forcibly detained and escorted to the new territory. Many would perish on this journey from starvation, cold, disease and violence. On May 13, 1846, the United States declared war against Mexico, who had provided it with a casus belli by attacking U.S. soldiers and besieging a U.S. fort in disputed territory. The U.S. federal government called on the states to provide volunteers for the war. The call to arms was so successful in Tennessee, that the 30,000 volunteers had to participate in a lottery to determine which 2,800 of them could join the campaign. The 20 year-old Levi was one of the fortunate few whose ticket was drawn and he enlisted in Company H of the 1st Tennessee Mounted Infantry as a private, under the command of Captain Gillespie. Mustered in Washington County, Tennessee on June 14th, 1846, the company rode 1200 miles southwest to west Texas, where they rode through the country, guarding against possible incursions by the Mexican army into disputed territory. Records show the regiment then marching into Mexico but Levi is honourably discharged on a surgeons certificate on October 12th at Camp Placedo, near Port Lavaca, likely fallen prey to the many illnesses such as typhoid and yellow fever that ravaged the volunteers. Regardless, his war was over and he was on his way home. Less than a year after his return to Tennessee, Levi and Rachel married on October 15th, 1847. Their first son, Columbus, was born the next year, in 1848, followed by a daughter, Margaret, in 1849. After the birth of Maggie, Levi and Rachel followed the example of many of their uncles, aunts, and cousins and migrated to Missouri. However, they settled in Barry County, several counties south of Johnson County, where most of the other Fergusons, including Levi's oldest brother, James, had settled. In Missouri, Levi and Rachel farmed and grew their family by two more children: Samantha around 1851 and Robert in January, 1853. Then tragedy struck. Rachel died sometime in 1853 or 1854. She may have suffered from complications from childbirth or it might have been disease, such as Cholera. Cholera, the “blue death”, swept through Missouri around this time, killing thousands of men, women, and children. The disease’s victims suffered from vomiting and severe diarrhea until they became so dehydrated that their skin became cold and clammy and turned a bluish grey colour. Many died within days or even hours. Levi was now left alone with 4 young children. Fortunately, he had family to help. He sent his children to stay with Brinkley and Atelia Hornsby in Johnson County, Missouri. Atelia’s maiden name was Falls and my best guess is that she was Levi’s aunt, this sister of his mother, Rachel Falls. Living next to the Hornsby’s was James Ferguson, Levi’s older brother. When Robert got older, he went to live with James.  United States 1854 United States 1854 Meanwhile, Levi had gone west into the Kansas Territory. In 1853, the U.S. federal government began the forced relocation of the Shawnee, who had earlier been forcibly relocated to Kansas, to new territory in Oklahoma. By 1854, this process was complete and on May 30, they formally created the Kansas Territory and opened it to settlement. At the same time, they also repealed the Missouri Compromise, which prohibited slavery north of the 36° 30´ latitude line. The new citizens of Kansas themselves would determine whether Kansas was slave state or a free state. The time of this “debate” was called “Bleeding Kansas” as the conflict quickly turned violent. To protect their national political power and preserve the institution of slavery, wealthy, slave-owning plantation owners wanted Kansas to join the Union as a slave state. They heavily advertised Kansas in states like Missouri, while they set up newspapers to inflame passions. Large number of land-squatters from Missouri quickly moved into Kansas, including Douglas County, around the town of Lecompton. Meanwhile, ardent and sometimes violent abolitionists from the north also whipped up emotions and encouraged settlement from non-slave states. Settlers in Douglas County with “free state” sentiment established the town of Lawrence, only 12 miles from Lecompton. Levi appears on a Kansas election list for the town of Lawrence on November 29, 1854, meaning he was one of the first settlers in the area. He also appears on a voter registration list for Lawrence on May 22, 1855. He also appears to have purchased 160 acres near Lecompton and located there in 1857. Tensions between pro and anti slavery groups in Douglas County were high, with rival newspapers stirring passions on both sides. Levi appears to have perhaps originally sided with his fellow Missourians, assisting to record signatures for the pro-slavery constitution in Lecompton. However, he appears to have then switched his loyalties. In November 1854, an army of 1,500 Missourians, well armed after raiding a federal arsenal, led by Douglas County Sheriff, Samuel Jones, attacked Lawrence. This siege came to be called the Wakarusa War, named after the nearby river. Abolitionists John Brown, who would lead an attack against Harper’s Ferry in 1859, and Jim Lane, who later served as a U.S. Senator and U.S. General in the Civil War, organized the town’s defense. A local citizen, Henry Learned, organized a company of men from Lawrence to defend the town with Levi Ferguson serving as his 1st Lieutenant. The siege ultimately ended with only one fatality and a truce that had Missourians withdraw back home. Personally, the most interesting fact to come out of this conflict was that Levi took up arms to defend the free-state town, despite his Tennessee and Missouri roots. Levi may have taken a moral stand or his actions might have been simple self-interest, defending his neighbors and town. Regardless, he it's clear that he discarded any loyalties to the pro-slavery cause. Jones led another raid later that year, causing significant damage to the town. John Brown’s followers retaliated by killing several pro-slavery settlers. However, eventually the federal government dispatched troops to the region to suppress the conflict and eventually the free-state supporters took control of the Kansas government. By 1860, Levi, now 34, had settled on a farm in Wakarusa Township in Douglas County, Kansas, right on the outskirts of Lawrence. His oldest son, Columbus, joined him there and he had a hired man to help him. His farm was one of the wealthiest in the community, valued at $7500. The violence in Kansas finally exploded nationally and the American Civil War began on April 12, 1861 with the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter. With a farm and family, Levi didn’t join the war. However, with his family spread throughout the border regions in Kansas and Missouri, there was no way he could escape the effects of the conflict. In 1862, Levi married Mahala Mitchell. Mahala was born in Tennessee in 1828 so it's possible that they knew each other growing up. Levi also had his children rejoin him sometime between 1860 and 1865, although it's unknown if that was before or after August 21, 1863.  Quantrill's Raid on Lawrence - Harper's Weekly September 5, 1863 Quantrill's Raid on Lawrence - Harper's Weekly September 5, 1863 Although Levi didn’t join the fight, the fight came to Lawrence. Missouri was a border state in the Civil War, split between north and south. However, it far more heavily supported the north, going as far as imprisoning the wives and children of Confederate guerrillas. One of these jails collapsed, killing 8 wives of Missouri Confederate partisans. Then Senator Jim Lane of Lawrence led a regiment called the "Jayhawkers" on raids into Missouri, killing Missourians they identified as siding with the Confederacy and confiscating supplies. Enraged, Missourian partisans, led by William Quantrill, launched a raid into Lawrence on August 21, 1863, destroying much of the town and murdering 160 to 190 unarmed men and boys. Quantrill was once a resident of Lawrence and a former school teacher. It’s very possible that Levi and Quantrill had known each other, as Quantrill had one time been a supporter of Senator Jim Lane. Tragically, Quantrill’s views had hardened against the abolitionist movement, to the point of extreme violence and murder. Fortunately, Levi and his family were unscathed from the attack. His farm lay right on the outskirts of town so it was unlikely that it was overlooked. Many residents escaped by hiding in cellars or cornfields or escaped into nearby ravines and it's likely that Levi, his heavily pregnant wife, and his children did the same, spending the night hiding in fear. In retaliation for the raid, Union General Ewing authorized General Order 11, which ordered the depopulation of 3½ Missouri counties along the Kansas border. Tens-of-thousands of Missourians were displaced from their homes and farms, which were torched to deprive the guerillas of supplies Johnson County, along the border with Kansas, would have been one of those affected. This county held large numbers of Fergusons, who now would have been homeless. Levi’s 1st cousin, 1x removed, Aaron Ferguson with his wife, Catherine Beck, and several of their children and grandchildren moved to Wakarusa Township, along with Levi’s older brother, James, and his family. However, soon after the Civil War ended, all the Fergusons, except Levi, returned to Missouri, where they reappear on the 1870 federal census back in Johnson County. Meanwhile, throughout the war and its aftermath,Levi and Mahala continued to grow their family, having 3 more children: Lizzy in 1863, Jennie in 1865, and James in 1866. After the war, Levi was involved in more mundane affairs. The value of his farm continued to increase, to $8000 in 1870, and he began to cultivate orchards. He was also involved with affairs in the community. Horse theft was a very serious crime on the frontier at this time, with punishments of long prison sentences or even hangings, Levi was called for jury duty to determine the guilt or innocence of Henry Clay, alias Clay Knoxy, in the theft of a horse from Christopher Barker. The local newspaper noted that both men were “colored”. After several hours of deliberation, Levi and his fellow jurors found Clay Knoxy not guilty. By 1875, Columbus and Robert and left to make their own fortune's and his eldest daughter, Maggie, married Thomas Marion Overstreet Nichols around 1867 and had many children. I’ve matched DNA with 3 of their descendants with my wife and father-in-law. Levi died on June 1, 1878 at his home of consumption at the age of 54, leaving behind a wife, 2 minor children and 4 grown children. His death notice in a local newspaper mentioned that he was a popular figure and his funeral was conducted by a local Methodist pastor. Robert Henry Ferguson, my wife’s 2nd great grandfather, married Elizabeth Rippey in 1887. They had 5 children, their eldest being Myrtie Ferguson, my wife’s great grandmother.  Oklahoma 1893 Land Run Oklahoma 1893 Land Run Following in the footsteps of his father, Robert and Elizabeth were some of the first settlers the newly opened Oklahoma Territory. We know the move was sometime before 1898, as their son Chester was born in Oklahoma in that year. Family legends suggest that they may have participated in the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1893, which is very possible. In 1905, Robert's and Elizabeth's eldest daughter, Myrtie Ferguson, married Leonard Isaiah Nicholson in Woods County, Oklahoma. On their application for marriage, Robert declared that he was a resident of Woods County, which was one of the counties created from the 1893 land rush. Myrtie and Leonard moved to Prince Albert, Saskatchewan in 1912 and had a large family of 13 children, including Elzora Rosy Nicholson, my wife’s grandmother, in 1921.. Levi had lived through one of the most tumultuous periods in American history and had seen much violence in his life, including slavery, wars, forced Native American relocations, and mass murder. He had fought against the forces of slavery and endured, became a prosperous farmer and good citizen, provided for his family, and left behind hundreds of descendants.  The Ancestry.com DNA test for my Dad have revealed no less than 32 genetic cousins with whom I can match a common ancestor. That's over double what I've discovered so far so it's pretty exciting. While many of these genetic matches provide evidence for ancestors that are already confirmed, there are several new branches in there as well. The closest match is a 1st cousin of my grandmother, Grace Davis. Unfortunately, I haven't yet been able to contact him so I only know him by his initial: W. Davis, the son of Benjamin Linton Davis, who was the brother to my great grandfather, Charles Elijah Davis. "W" and my father share about 6% of DNA, which is consistent with 1st cousins, 1x removed. If anyone who knows who "W" might be, please let me know! Here are a list of the closet common ancestors for these new matches: -- Joseph Henry Davis (1854-1931) and Delilah Grace Berlinguet (1858-1931) -- Sampson Coumbs (1808-1881) and Grace Cole (1807-1857) -- Mark Heathcock (1805-1880) and Alice Jones (1806-After 1860) -- Isham Norton (1752-1833) and Eliza Walker Calhoun (1755-1825) -- Christian Ritschhart (1739-1809) and Sophia Mitz (178-1855) -- Christian Ritschhart (1709-1790) and Magdalene Wolff (1703-1766) -- James Harper (1800-1869) and Alice Shillito (1810-1884) -- Edward Shillito (1765-1838) and Sarah Scott (1780-1850) -- Simon Fournier (1721-1771) and Elisabeth Thibault (1733-1804) -- Guillaume Thibault (1693-1786) and Marie-Francoise Bacon (1697-1765) -- Joseph Jalbert (1699-1756) and Marguerite Aubertin (1707-1781) -- Pierre Ranger (1696-1787) and Genevieve DuBois (1707-1784) -- William Hall (1708-1764) and Hannah Richardson (1710-1784) -- Clement Simpson (1778-1838) and Minty Dutton (1788-1844) -- Richard Rich (1637-1692) and Sarah Roberts (1643-1692) Of course, genetic cousins with common ancestors in our family tree does not absolutely confirm that the ancestor is correct for either of us. For example, we could have another common ancestor of whom we are both unaware. However, it is a significant piece of evidence, especially when my Dad has several genetic matches with the same ancestors, which is the case here with almost half this list. There are several French Canadian ancestors on this list, which was no surprise to me. I've learned that Quebec has amazingly good records so people with French ancestry have excellent family trees. So how accurate are these DNA ethnicity tests? Here is a rough estimate of my father's actual ancestry, based on the paper trail:

* The Colonial American ancestry is too difficult to break down further but it consists of Scottish, English, Irish, German, African, and Native American ** The Québécois ancestry has a trace of Italian and Portuguese but mostly traces back to various regions in France If you are reading the above colour-coded chart correctly, you'll see that my grandmother, Grace, is 50% Scottish, 25% Irish, 12.5% Québécois , 12.5% Cornish. She's clearly very Celtic, which is probably why Ancestry.com DNA gave my father a 43% Irish (Native Briton) percentage. Here is the 23andme speculative breakdown for my father's ethnicity. I've moved the paper trail percentages into the 23andme category where I feel it fits best.

So 23andme is far more precise than I could be, although if I were to guess at the actual percentages in Colonial American, it would be very close to what 23andme suggested.

The French and German category is obviously too low but German is notoriously hard to categorize. For example, English people have significant amounts of German DNA from the Angles and Saxons. A lot of this German DNA probably ends up in the Broadly Northwest European for that reason. All-in-all, it looks like 23andme does a pretty good job with ethnicity testing. I'm actually surprised at the precision and accuracy. Of course, 23andme has a huge database of DNA from western Europe so perhaps I shouldn't have been. People with ancestries from other parts of the world are probably less impressed. The Ancestry.com DNA results for my father are in.

These results are a little different than 23andme as they use different sample populations for the analysis. 43% Irish (Native Briton) 31% Europe West (French and German) 12% Iberian Peninsula (Spanish, Portuguese, southern French) 6% Scandinavian <1% African Southeast Bantu <1% Native American For comparison, here is his standard view 23andme: 46.7% British and Irish 42.4% Broadly Northwest European 1% French and German 6.6% Broadly European 1.4% Sub-Saharan African 0.7%Native American So other than the odd Iberian percentage, which may really be southern French, they match pretty closely: Native Briton, Anglo-Saxon, French, German, Scandinavian, and likely a distant African and Native American ancestor. That matches the known family tree very well. The far more interesting result of this testing is all the genetic cousins it found. Better yet, genetic cousins with good family trees. There is another Davis cousin, several Ritschhart cousins, more Hathcocks, and several Halls, which are new and exciting. There is even someone who might be a 8th cousin, with a common ancestor deep in the Dutton tree. This has been so useful that I think we need another round of DNA testing! |

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed