|

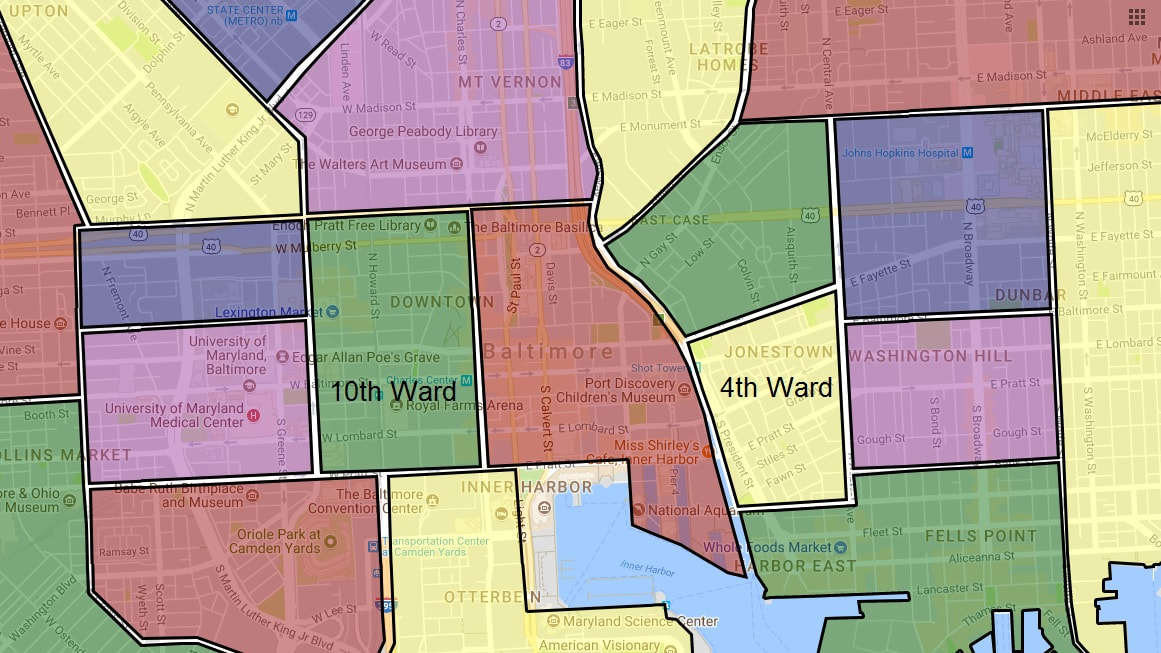

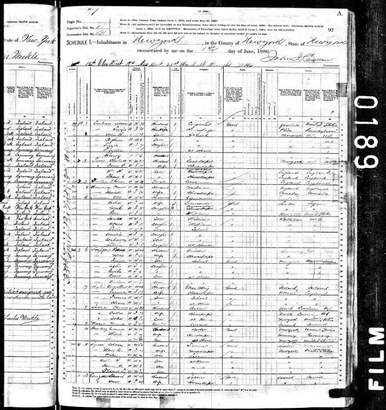

Edit: Sadly, a new document proved all this conjecture was wrong. Indeed, Sarah from these records did go by the name Sadie. Indeed, she did lie about her age and birthplace, saying she was born in about 1866 in Baltimore, but she married a different man. Two Sadie Simmons from Baltimore? Sigh. Edit 2: Well, it turns out this conjecture was all correct after all. There was only one Sadie Simmons and she did marry Moss Aarons and she also had a family with Isidor Teschner, aka William Tabor. What a tangled web we weave... I wrote about Sadie a couple years ago, along with the troubled relationship between her daughter, Mildred, and son-in-law, Russell. Earlier this year, I discussed how a strong DNA match with a Jewish Englishman gave us a clue to the identity of Sadie's father. In fact, two more DNA matches point to a relationship with a Simmons family of London. On the 1900 and subsequent census, Sadie claimed she was born about 1867 in Baltimore, Maryland, her given name is Sarah, that both her parents were born in England, and that her maiden name was Simmons. However, while there are a few Sarah Simmons in 19th century records, none are consistent with all those facts. Either she somehow evaded every census or she is being misleading about some details of her past. After tracing the Simmons lines of our DNA matches back back to Levy Simmons (1794-1842) and Sarah Cohen (1799-1885) and then back down to find their descendents, I found that two Simmons sons, Abraham and Aaron, lived in Baltimore about the same time Sadie was born. However, I can find no evidence of Aaron being married or having children. On the other hand, Abraham is married and has several children, including a daughter named Sarah, but she is the wrong age and was not born in Maryland but in New York. My first thought was the Aaron might somehow be the father. Perhaps he didn't take responsibility for the child but instead gave her to friends to be raised and she took their name. Then I took a closer look at Abraham's family. In 1860, Abraham and Aaron were both cigar makers, living in the 4th ward of Baltimore, which was a very ethnically diverse and poor region of the city, filled with Germans, Jews, Poles, Irish, and African Americans. The people in this neighborhood had professions such as brick layer, shoemaker, bricklayer and machinist. Abraham was married to Rachael and had one daughter, Sarah, who was born in 1859 in New York City. At this time, the city was experiencing an upsurge of nativist sentiment and many anti-immigrant "clubs" arose, such as the Plug Uglies, Rip Raps, American Rattlers, and Blood Tubs. These clubs were frequently involved in parades and torch lit processions that marched through many different neighborhoods, often sparking clashes with residents that devolved into violent brawls and riots, where many of the participants were armed with picks, axes, and even muskets. Over the next ten years, in the midst of the Civil War, Abraham and Rachel had five more children and moved to the 10th ward, a very similar neighborhood to the 4th ward. In 1870, Abraham, 35, was still a cigar maker while Sarah and her two oldest sisters attended school and the youngest children remained at home with Rachael, 37. By 1880, Abraham and Rachael had moved the Murray Hill neighborhood of New York City. While many wealthy people lived in this neighborhood, the Simmons were not one of them; their immediate neighbors were coachmen, servants, carpenters, bookkeepers, and glass cutters. Rachael no longer described herself as keeping house but as a cigar maker, suggesting that now that her children were older, she joined her husband in the family business. With automation pushing down the prices of cigars, they had also put their older children to work. By this time, they had 3 more children, completing the family:

There is no 1890 census, it was destroyed in a fire, but Abraham died in 1899, leaving us to find Rachael as head of household on the 1900 census.

Interestingly, Agnes gives her age as 27 but supplies her actual birth year of 1863, which places her age correctly at 37. The person supplying the census information gives Amelia's her age as 25 and her birth year as 1875, when at the 1880 census she was said to be 9, so born in 1871. Lillie gave her birth year as 1878 and age as 22, when she was 5 and in school on the 1880 census so 25 in 1900. A mistake of several years on a census is not uncommon, we have no idea who supplied the information. However, there is evidence the ages were deliberately incorrect. In 1901, Lillie married Jacob Klausner appears in several records afterwards, in which she consistently provided her age as 3 years younger than the reality. On the 1910 census, Agnes shaved many more years from her age, claiming she was 25, which would have had her born in 1885. Since her mother, now 75, was clearly too old to have a 25 year old daughter, her age was reduced to 65. In case you think this was an accident, Agnes married Edwin Rosenfield in 1914, when she was 50 and Edwin was 34. This is almost certainly the same Agnes, as the marriage certificate lists Abraham and Rachael Simmons as her parents. Afterwards, whether or not Edwin knew the truth, on the 1915, 1920, 1925 census, where she consistently provided her age as being born in 1878, a whopping 13 years younger than her actual age. Given at least two of the daughters were unabashed about shaving years from their age and maintaining that fiction, it seems possible that Sadie could have misremembered her age as well. However, if this is our Sadie then she was in New York in 1880 but had her first child in 1893 in Philadelphia, before moving to Atlanta, and then back to New York in 1900. How did she meet Isidor "William" Tabor? William's occupation on the 1900 census was salesman, and given that the family moved from Philadelphia to Atlanta to New York within a few years, suggests that his career was on the move. It's certainly not a stretch to believe he might have lived in New York in the early 1890s when he met Sadie. If Sadie was 33 when she met the 27 year old William, it's possible that, with the encouragement of her family, she shaved a few years off her age. After William died about 1905, Sadie became a dressmaker, which was Sarah's earlier profession. While this is consistent with them being the same person, it's not strong evidence as dressmaking was a very common trade. What's also interesting is that since 1900, Sadie always lived within a dozen blocks of her mother and some sisters, even as they moved around Manhattan. Of course, so did many thousands of other people.

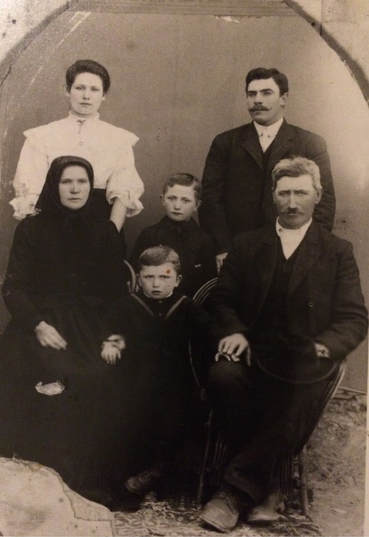

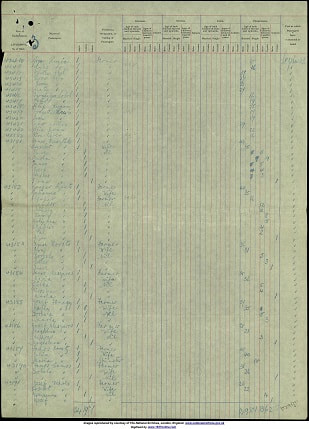

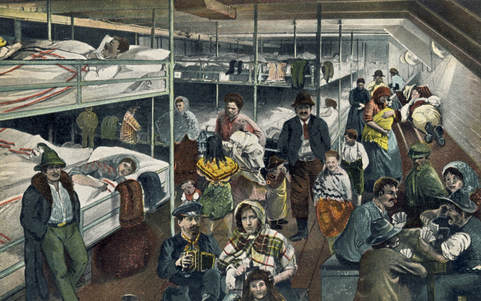

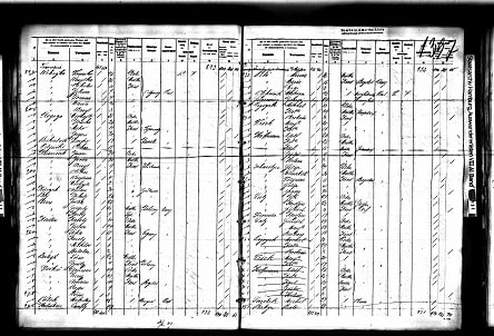

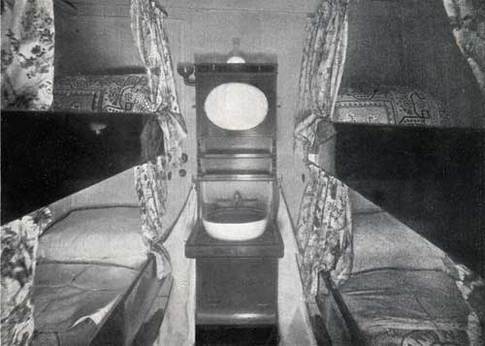

There is also the issue of religion. Sadie was Episcopalian while there is no indications that her family ceased being Jewish. If this is Sarah, was William the one who converted her? Did it have something to do with her experience in a very diverse and turbulent Baltimore? While all of this reasonably fits facts, this relationship is far from proven. The next step is to find some closer Simmons relations and get them to spit in a cup. My grandparents, Julia Debreceni and Ben Daku, were the first generation of my mother's family to be born in Canada. Their grandparents and parents immigrated to Canada in 1902 and 1903, settling in the R.M. of Hazelwood in southern Saskatchewan, in a colony that the founders had dubbed Bekevar, the "fortress of peace". To again touch on their reasons for leaving Hungary: by 1900, Hungary had been gripped in an industrial revolution for the last few decades. While rapid modernization improved standards of living, it also created a population boom, resulting in a sharp increase in the price of land. For my agrarian ancestors, this was a crisis as it meant that their children might need to adopt new trades and move away to crowded urban centers for work. Worse, there were rumors of war. According to my great-grandfather, Alex Daku: “Farmers used to call in (to my father’s bootmaker’s workshop) to discuss politics and other public affairs. It was there that I heard, for the first time, about the brilliance of Louis Kossuth, the rest of the heroes of the War of Independence, and its events. It was there that I was first told by the pious peasants that war was in the offing. In the first instance, because very many young men had been called up and secondly, because Louis Kossuth had returned from Italy in disguise, in order to visit every community and call upon the people to rise again and fight for freedom.” In times of war or nationalist unrest, Hungarian men were drafted to serve in the Austro-Hungarian Imperial army for 3 years, with a 10 year obligation to the reserves. While war did not erupt for several more years, it was bigger and more devastating than anyone could have imagined. In the face of these tensions, four different families, the Dakus, Debrecenis, Fonagys, and Dakus, each made the decision to depart Hungary, following the siren call to America. Yes, I wrote Dakus twice. Both Daku families were from the same village so likely related but it was distant enough that they didn't know how. Most Hungarians migrants settled in the United States, often finding manufacturing jobs in the booming northeast or midwest. but my ancestors were determined to remain farmers. After reading the letters from their sons abroad, they decided to migrate to Saskatchewan, where 160 acres could be had for only $10. They had made their choice but now they faced the logistical and financial challenges of transplanting their families. My family were craftsmen as well as farmers, so they likely earned at least 800 forints per year, which was two or three times the wages of a peasant farmer. Train tickets to Hamburg could cost the family over 100 forints and the passage across the Atlantic might cost 500 to 800 forints, depending whether they travelled 2nd class or steerage. They would also need to cover the cost of food and shelter on their journey, as well as the train trip out to Saskatchewan, which could cost over 200 forints for a 2nd class sleeper car or half that for a colonist car. Once at their new homes, they would face barren grasslands, with no seed, plows, horses, houses, stores, or even lumber with which to build anything. The nearest town would be over a hundred miles away so everything would need to be imported by rail, which would cost yet more money. Of course, since the entire family was emigrating, these expenses were largely covered by the sale of the family farm and non-transportable belongings. Letters from those who went ahead advised them to travel light, since many tools or goods would be taxed on arriving in North America and it was relatively inexpensive to replace them. They would leave everything behind in order to build anew. The next section discusses the journies of each of my four sets of 2x great grandparents: Fonagy, Daku, Debreczeni, and Daku. It was a day in early spring when my grandfather's maternal grandparents, Fónagy József and Szántó Zsófia, and their two daughters, Borbála, 5, and Maria, 3, departed the village of Tornyospálca. The weather was cool but little snow would have still been on the ground. They walked the few miles up the dirt road to the railroad station, possibly pulling their suitcases and trunks behind them on a handcart, to board the steam locomotive for the nine-hour trip to Keleti railway station in Budapest. Note: you may have noticed that I'm using the Magyar names. Not only does Barbara become Borbála and Ben become Bálint but the surname comes first and the given name second. When I write their western names, I put each in the "correct" order. Rail lines from Budapest ran west to Vienna and Paris but we don't know which the Fonagys took. Regardless, they eventually made their way to the coast, where they took passage to Liverpool, England. While this appears to be an unusual city for Hungarians to depart for America, it's possible that agents working for the shipping lines were advertising in Hungary and the Fonagys selected them, possibly based on price. On April 1st, 1902, the family boarded the S/S Lake Ontario, a 392 foot long steamship owned by the Beaver line, which would carry 1166 passengers on this trip: 891 adults, 221 children, and 84 infants. Their fellow emigrants were mostly farmers of German, Polish, Hungarian, Ukrainian and other Eastern European ethnicity. The voyage delivered them to St. John, New Brunswick, from where they would have departed for Saskatchewan by rail soon after. My grandmother's maternal grandparents, Daku András and Kaponyás Terézia, and their children, András, 14, Lajos, 9, and Luiza, 3, departed Bezdéd about the same time as the Fonagys left Tornyospálca, in the early spring of 1902. Bezdéd was only a few short miles from Tornyospálca so it's likely they knew of the departure of the Fonagys and other families to Bekevar. Their two eldest sons had already went on ahead to America. Sándor had arrived in New York first, on March 4th, 1901, where he stayed with some cousins for a short time, then moved to Pennsylvania. His younger brother, Elek, arrived in New York City on September 20th, 1901. The brothers wrote home favourably about the prospects for work in the United States but they soon received a letter from their parents asking them to rejoin the family in Saskatchewan. Although the Dakus had decided on Bekevar, they still followed in their son's footsteps, taking the train to Hamburg, Germany, a busy port city, and popular point of departure for many emigrants to the new world. The Dakus boarded the S/S Armenia on May 31st, 1902, a 399 foot long steamship of the Hamburg-American line. The least expensive option, steerage meant sleeping and living in a common area, with no separate cabins for sleeping, eating, or recreating. The families, single men, and single women were all segregated from each other to reduce some stress but it was still tight quarters with little privacy. Fortunately, passengers could take a turn on deck but even their deck space was limited, with 1st and 2nd class passengers getting the lion's share. The ship was to carry 1097 passengers to Halifax, Nova Scotia: 761 adults, 254 children, and 82 infants. The passengers were mostly farmers and laborers from Ungarn (Hungary), Österreich (Austria), and Russland (Russia). Interestingly, berthed with the Dakus were two widows from Bezdéd and nearby Zahony, each with a lone child, both of whom would settle in New York City. My grandmother's uncle, Debreczeni Petér, was the first of her paternal family to arrive in North America. Departing from Hamburg, Germany on August 13th, 1902, he arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Like Sándor and Elek Daku, he was likely scouting out locations for the family's resettlement in America and Canada so perhaps he was the one who learned of the colony and wrote home about it to his parents. My grandmother's paternal grandparents, Debreczeni József and Jonás Juliánna, with their children, Maria, 18, Lorincz, 9, and Pal, 5, departed Karcag, in central Hungary, six months later. While all my other Hungarian ancestors lived in a small cluster of farming villages and certainly knew each other, perhaps even planned their resettlement together, the Debreczenis were part of another wave of immigration. In Bekevar, the Debreczenis would be known as the wealthy Hungarians and they described themselves as businessmen, rather than farmers, so perhaps they traveled a bit more comfortably than most. However, like the Dakus, they took the train to Hamburg, Germany. On March 7th, 1903, the Debreczeni family boarded the S/S Pretoria for a 2nd class cabin, a 560 foot steamship bound for New York City. Since they sailed to New York rather than directly to Canada, the family may have purchased their tickets months ago, before they had made their final decision. Travelling in 2nd class meant the Debreczenis would have their own sleeping cabin, as well as a dining saloon and smoking room, a much more comfortable way to travel. The family would arrive in New York on March 23rd, 1903, where they were likely examined aboard the ship, avoiding transport to Ellis Island and the long queues to await examination and processing. Unless something drew the examiner's attention, they would have just strolled down the gangplank into New York. Also migrating to Canada from Bezdéd in 1903 were my grandfather's paternal grandparents, Daku Károly and Veres Erzsébet, along with their children, Bálint, 16, Károly Jr, 11, and Bernát, 3. Although, I can find no record of their journey, there are records of Károly's older brother, János, moving to New York City, where his descendants still live today. All of my family would have then had to make their way west by rail. The Dakus and Fonagys may have made the week long journey in a colonist car, sitting on the rowed bench seat, taking turns sleeping on the fold out bunks in the back, using the two toilets, or cooking on the single stove. The Debreczenis, of course, likely travelled in their own cabin, with their own toilet, eating in a separate dining car. Fortunately, they all took the trip in the spring, when it was not too hot or too cold. After days of viewing the picturesque forests and lakes of Ontario and Manitoba, the last leg of their journey greeted them with what must have seemed to be endless, empty grasslands, except for a few small towns and NWMP posts. Eventually, they arrived in Regina, a "city" of 3,000 people, many times smaller than town of Karcag, although it would grow tenfold in the next decade. It was there that they applied for their homesteads and received their 160 acres for every man over eighteen. Of course, there were the following conditions:

Their new land was covered with stones and scraggly bush with sloughs that filled with rainwater and made the surrounding land swampy. Earlier Hungarian settlers would have occupied the area a couple years earlier and could have assisted them in marking their land and heading back to Regina document the claim.

To build homes, they hauled logs from the woods around Kenosee Lake, cut them to size and mortared them together. The book Peace and Strife by Martin Kovacs describes the house: "The chinks between the logs were plugged with a mixture of clay-mud, prairie wool, and hay. After the mud portions had dried out, in a few days, sod-squares were placed on poplar poles with hay in between the two layers. As the prevailing weather of those first years tended to be wet, the Szabos and the other early settlers had to undergo the experience of dripping roofs, wet bedding, and general dampness inside their houses." Within few years, the Hungarians would set to work building better homes, though. All except my Debreczeni 2x great grandparents, of course. They would purchase a mail order house. |

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed