|

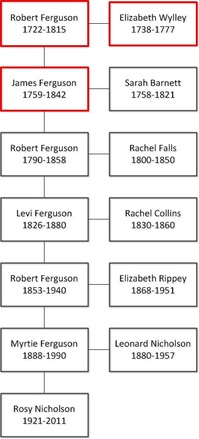

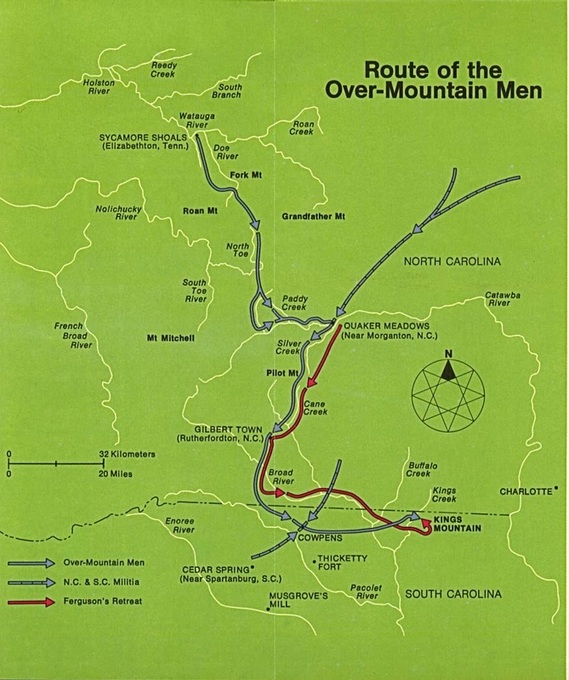

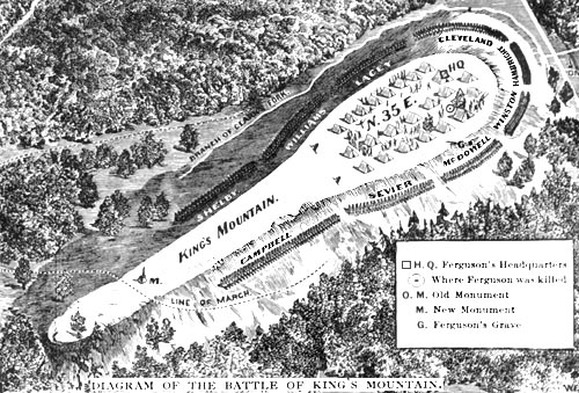

On a warm March evening in 1777, near the frontier in southeastern North Carolina, six men rode up the road to the Ferguson farmhouse. This event would not have provoked any alarm in Robert Ferguson, the ancestor of my wife's great grandmother, Myrtie Ferguson; he was accustomed to providing food and provision to Patriot militiamen, who often patrolled the North Carolina countryside, scouting for Loyalists or Cherokee raiders. The American War of Independence had begun less than a year ago but, in North Carolina, it was more of a civil war between neighbours than it was a war against British armies. Perhaps as many as one in six North Carolinians supported Britain and the majority pro-Independence population viewed them with deep suspicion. There had already been one large battle with the Patriots defeating and capturing hundreds of Loyalists paroling back to their farms. Patriots sought to intimidate the Loyalists, sometimes even expelling them from their homes and confiscating their property. If anyone were found to have directly supported the British effort, they were arrested and tried. If found guilty, they might even be hanged. Loyalists responded with violence of their own, sometimes with arson and murder, and the countryside seethed with violence and anger. At the Ferguson farm, Scottish born, 55 year old Robert Ferguson was not alone. At home with him were his wife, Elizabeth, 39, and his many children, including his eldest son, James, 17. Both Robert and James had recently returned from a 3 month tour with the Patriot militia, riding with Captain John Barber to patrol along the edge of the Blue Ridge mountains. The leader of the men who approached the farm identified himself as Sam Brown and he declared that he and his men were Patriots, seeking for supper for themselves and feed for their horses. Patriotic and civic minded, Robert granted their request and the men were invited to sit down with him for supper. Before the meal, displaying apparent devoutness, Brown asked Robert to give a blessing, which he did. The meal was likely full of conversation about recent events. Only a few months previously, North Carolina had adopted their new constitution and a radical declaration of rights. Closer to home, Cherokees desperate to defend their land threatened Patriots and Loyalists alike. What Robert and Elizabeth did not know was that the Sam Brown whom they had invited to supper was well on his way to establishing a reputation for himself. Brown had once been married but was so abusive of his wife that she returned home to her father. In revenge, Brown snuck up on their farm one night and slaughtered all the livestock. Since then, he had earned a reputation for assault and robbery. The events at the farm were recorded much later, on March 4, 1880, by Lyman Draper, an historian who collected stories and biographies of people who had lived through the Revolutionary War. This account was related by Daniel Kennedy, who was told the story by one of Robert’s sons: “After this was over they were seen in secret counsel the sequel of which they came into the house and knocked the old man (Robert) down and beat him until they thought he was dead. Seizing the guns in the rack, confining and tying the oldest son James Moses made his escape. Robert was punched in the side with a gun breaking 2 of his ribs. One of the party pushed one of the little boys in the fire. Old lady (Elizabeth) pulled him out for which another threw her with violence against the table after which she never spoke. Moses that escaped alarmed the neighbourhood who collected and the distressing scene of the dead mother a father scarcely alive but did live but never was able to do anything.” Elizabeth was dead, Robert was severely wounded, and the children may have suffered significant injuries during the attack. Sam Brown and his henchmen fled south into South Carolina with all the family property they could carry and probably all the horses. While Kennedy’s story claimed that neighbours hunted down the culprits the next evening, he provides a location over a hundred miles away, so it was very unlikely that it happened so quickly. According to James’s own declaration at his pension hearing in 1832, his neighbours mustered a company to pursue Brown on April 1, 1777. James testified that he volunteered his service to the company and joined the hunt. Tracking the robbers to South Carolina, they followed the south fork of the Catawba River into the Piney Woods, where they found Brown and his friends. According to Kennedy, the company attempted to capture the robbers but Brown fought back vigorously. After an exchange of musket fire, 4 of the robbers were shot dead but Sam Brown eluded his pursuers. James retrieved most of his family property and the company returned to North Carolina, where James soon left them and returned to his family. James remained home for the next few months as his father convalesced. Yet, by the autumn, with the harvest in, James volunteered again. Over 3 years, James joined the militia for 6 tours, often serving under Captain Isaac White. Most of these tours were in the autumn or winter, indicating that James signed up for service whenever he could be spared from the farm. Sometime in this period, Robert remarried to 40 year old Isabel Dickey, the widow of Thomas Barr, and she and her children moved in with the family. Meanwhile, the real war drew closer to the Fergusons. The British had invaded Georgia and South Carolina and many of the young men of North Carolina left to join the American Continental Army or serve beside the Continentals as militia. On May 12, 1780, only 250 miles to the southeast, the British seized Charleston, South Carolina, capturing 5,000 American soldiers. Only 3 months later, on August 16, 1780, at Camden, South Carolina, only a little over 100 miles south of the Ferguson farm, the British utterly destroyed the Continental Army. The British were coming north and it appeared there was no American army left that could stop them. General Charles Cornwallis led the main army north towards Charlotte, North Carolina, while, on the left flank, Scottish Major Patrick Ferguson, no known relations to our Fergusons, led a force of 1,000 Loyalist volunteers toward Gilbert Town. However, as General Cornwallis and Major Ferguson marched north, North Carolina militia and frontiersmen from over the Blue Ridge Mountain, called Overmountain Men, harassed their columns, fighting “Indian” style in a series of terrifying hit and run attacks. This enraged Major Ferguson, who threatened to cross the mountains and “lay waste to your country with fire and sword.” Predictably, these threats did not intimidate the frontiersmen but enraged them. The Overmountain men poured across the mountains and headed towards Gilbert Town, sending riders in all directions to summon help. One of these Overmountain men was John Crockett, the father of the famous Davy Crockett. Swift riding Patriot messengers soon rode through the countryside with a call to arms and James Ferguson once again joined the Horse Company of Captain Isaac White. The sixty militiamen rode hard for Gilbert Town, sleeping on the ground and foraging for raw turnips or raw corn to eat. At Gilbert Town, they joined the command of Colonel James Williams, who led over 300 South Carolina militia and 30 Georgians, and now rode for Cowpens, South Carolina, where they joined the main Patriot army in pursuit of Major Ferguson. Instead of withdrawing, the aggressive and innovative Major Ferguson determined to fight the Patriot army. He chose the forested hill of King’s Mountain as his battleground, expecting the high ground would give his Loyalist army an advantage. The hill was also only 30 miles from Charlotte and he sent messengers to Cornwallis, asking for reinforcements. The British armies at King’s Mountains and in Charlotte were only a few miles from the Ferguson farm. With Major Ferguson threatening to lay waste to the rebellious countryside and with center of action drawing so close to his home, James had to be anxious with this state of affairs. Fearing that Major Ferguson was planning to run for Charlotte, the Patriot leaders at Cowpens decided to push hard for King’s Mountain. At 9PM, on October 7th, as light rains turned the roads to a muddy mess, the 900 of the swiftest Patriots rode all day and night to catch the Loyalist army. Undoubtedly exhausted, James rode with them. He would have been soaked to the skin, having removed his topcoat to wrap around his rifle so it would be ready to fire once he encountered the Loyalists. Both the Patriots and Loyalists were dressed in civilian clothes so, to identify friend from foe, the Patriots wore a piece a paper in their caps while the Loyalists wore twigs in theirs. The Patriots were armed with hunting rifles, knives, and tomahawks while the Loyalists had British made “Brown Bess” muskets and deadly bayonets. Hidden by rain, the Patriots managed to approach the mountain undetected. Dismounting in the trees, they quietly encircled the Major Ferguson’s encampment. However, Loyalist lookouts spotted their movements and the Loyalists beat to quarters. The Battle of King’s Mountain commenced at 1 O’clock in the afternoon on October 7th. Unfortunately for Major Ferguson, Cornwallis in Charlotte, because of illness or a dislike of the Major, did not send reinforcements. Surrounding the Loyalist encampment, the Patriots fought independently in a shoot and move, “Indian” style attack while the Loyalists stood behind a ring of rocks and wagons on the hilltop. James would have advanced up the hill, running from tree to rock, quickly loading his hunting rifle and only exposing himself long enough to aim and shoot at a Loyalist. On higher ground, the Loyalists tended to overshoot their targets while the Patriot fire was far more deadly. On all sides, the Patriots advanced up the hill, pushing the Loyalists back. With bayonets fixed, the Loyalists repulsed the Patriots back down the hill at least once but then they returned to the hilltop once more and the battle continued. As they neared the hilltop, Patriot sharpshooters spotted Major Ferguson, riding his horse back and forth behind the line,wearing his bright checkered coat and blowing his silver whistle to direct his troops. The Patriots immediately targeted the Major, shooting him several times, until he fell from horse, getting his foot caught in the stirrup. No longer under the control of its master, the horse ran down the hill, into the ranks of the Patriots, dragging the mortally wounded Major Ferguson behind. The Loyalists quickly offered their surrender, although the Patriots continued to fire for several minutes before accepting it.

With Major Ferguson's defeat, yellow fever plaguing his soldiers, and his supply lines under constant attack, General Cornwallis withdrew from Charlotte, back to South Carolina. After a year of constant defeats, this was a pivotal battle that turned the course of the war. After the Battle of King’s Mountain, James returned home. He would soon hear even more welcome news: the robber Sam Brown had finally been killed. After murdering Elizabeth Ferguson and escaping his pursuers, Sam Brown joined the Loyalists as a Captain. In the summer of 1780, Brown molested and threatened the wife of a Patriot Colonel. Colonel Josiah Cuthbertson tracked Brown to a farmhouse 12 miles away and waited in ambush for him to emerge. When Brown stepped out of the door, Cuthbertson shot him dead. James would volunteer twice more before the end of the Revolutionary War but never saw any further action. With the end of the war, North Carolina rewarded its volunteers with grants of land over the Blue Ridge Mountain. Robert and James Ferguson obtained land in what is today Rhea County, Tennessee, named after John Rhea, another veteran of the Battle of King’s Mountain. However, while some Native Americans were happy to sell their lands to Americans, many others, supported by British arms and support, did not acknowledge those sales and aggressively raided and attacked settlers. It was not until 1818 that military campaigns by future president, Andrew Jackson, forced Native Americans to surrender their claims to most of the state. Robert Ferguson died in 1815, leaving his North Carolina property to his second wife and her children and his Tennessee land to his sons and daughter. On April 10, 1789, James married Sarah Barnett, set up their own farm in Lincoln County, North Carolina, and had many children, starting with their first son, Robert, named for his grandfather, in 1790. In 1819, Robert married Sarah Falls and, the same year, almost the entire Ferguson clan picked up stakes and moved to their now secure land in Rhea County, Tennessee. James Ferguson applied for his Revolutionary War pension in 1832 and received $78.33 per year until his death in January, 1842. Robert and Sarah had several children, including their third child and second son, Levi Ferguson, born in 1826, of whom I have written about here. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed