|

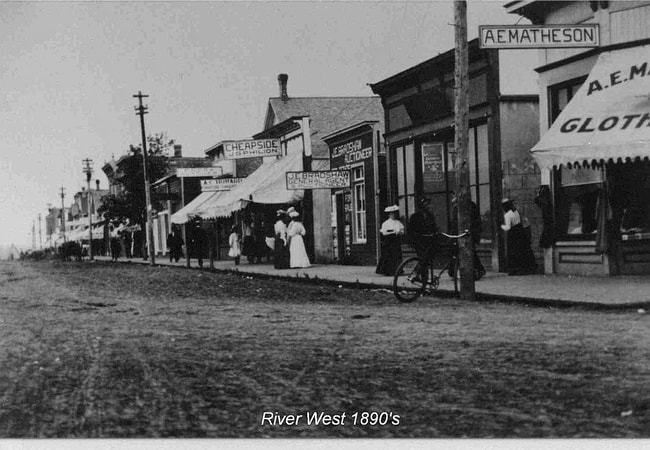

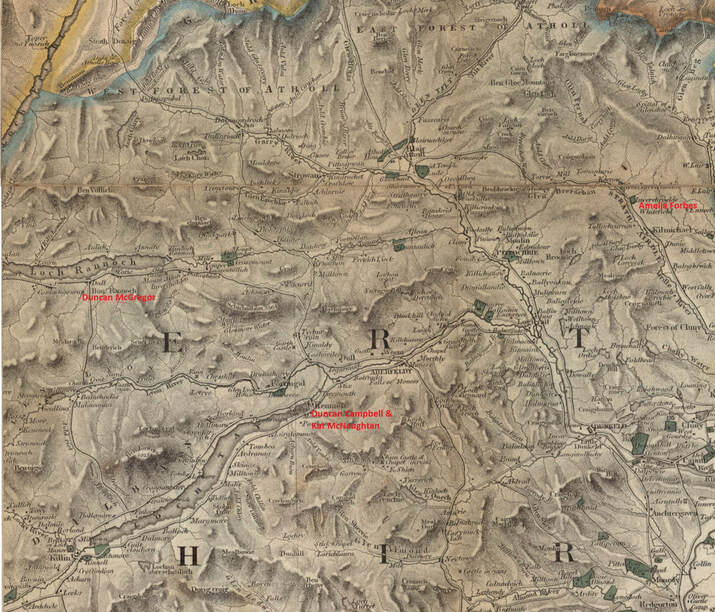

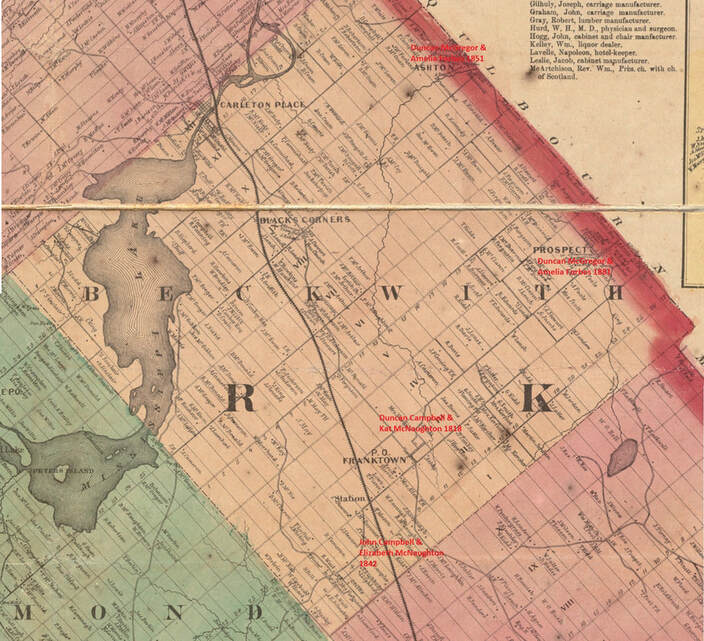

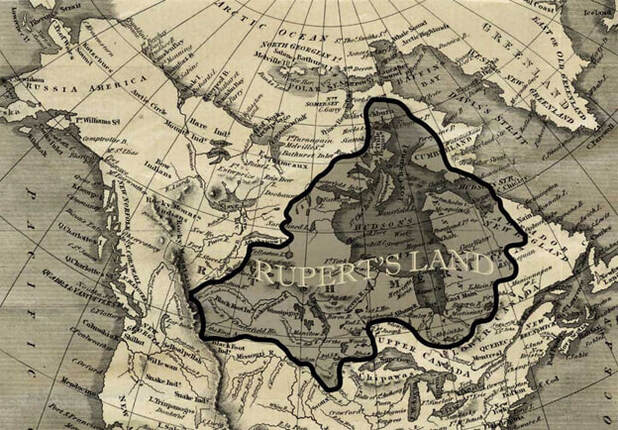

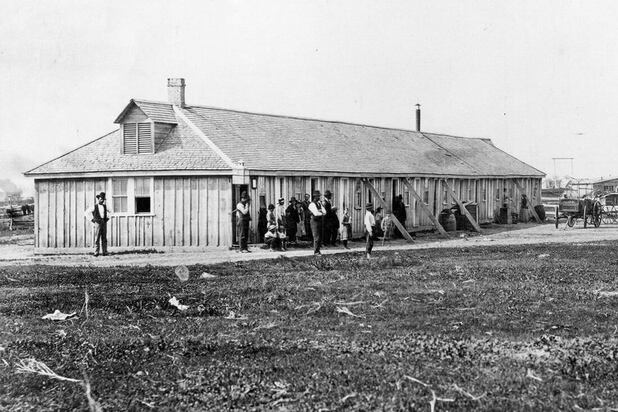

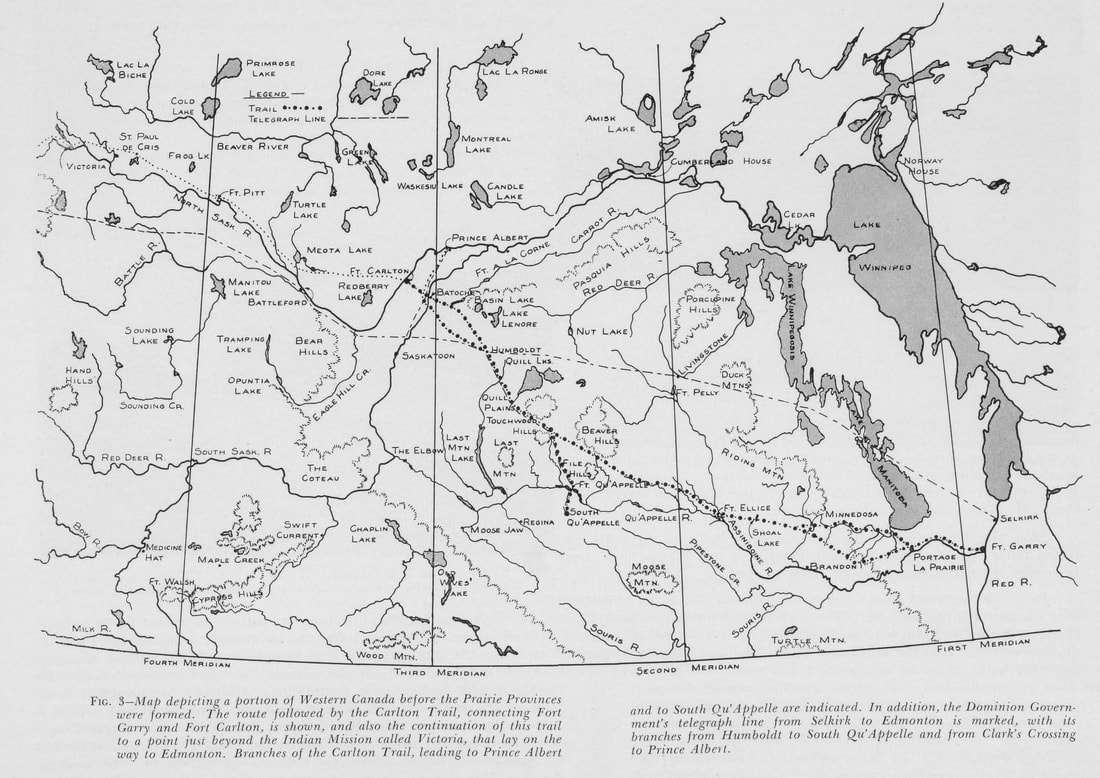

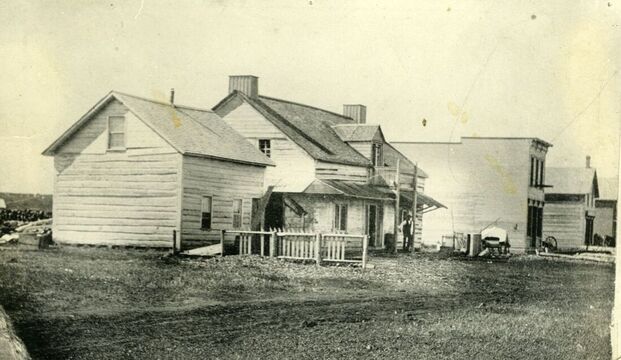

Lucy Maud Montgomery, 15-years-old, future author of Anne of Green Gables and Emily of New Moon, arrived in Prince Albert at 4 o'clock in the afternoon on Wednesday, August 20th, 1890, 3000 miles from her former home on Prince Edward Island. She had taken a passenger train to Regina, which she described as "not a bad little place but the country around it is the nearest approach to a desert of anything I have ever seen." She then rode in the caboose of a freight train to Duck Lake, and from there almost 60 kilometres northeast by buckboard and wagon across territory "fair and green and fertile-looking," "jammed with flowers... the prettiest of which were the exquisite little bluebells", into the city, "a pretty little town -- rather 'straggly,' built along the river bank." Maud would live in Prince Albert over the next year, with her father, John Hugh Montgomery, and her step-mother, Mary Ann McRae. Homesick, she returned to the island a year later, but not before forming several close attachments, including with "Holdenby and Stevie and Miss Cassie and the McGregor girls." The McGregor girls were Nellie, Robina, Kate, and Alexina, who all lived in their parents' home, my 3x-great-grandparents, Duncan McGregor and Amelia Forbes. P.R. Ritchie described the Prince Albert district in 1892: "The North and South Saskatchewan Rivers, which have their source in the Rocky Mountains, run parallel with each other for a distance of eighty miles, from twenty to thirty miles apart, and join twenty-four miles east of Prince Albert. Between these two rivers, the country is well settled. Settlement began here fifteen years ago, long before railways were dreamed of in the country. Prince Albert itself is a very old settlement, a mission having been formed here many years ago. To-day it has three lumber mills, two flour mills, and thirty stores. The town is well lighted by electricity, and there is a system of telephones all over it." In 1878, long before railways were dreamed of in that country, 28-year-old Pete Campbell rode in to town to stake his claim. The CampbellsMy 2x great-grandfather, Peter George Campbell, was born to John Campbell and Elizabeth McNaughton on April 25th, 1851, on the family farm in Canada West (Ontario), the 4th of 8 children. As Pete's grandson, Arnold Davis, described, "he came from farming stock." Pete's father, John D. Campbell, had been born in the Scottish Highlands about 1808 to Duncan Campbell and Catharine McNaughton, both from Kenmore, which lay on the far east end of Loch Tay. A mile up the River Tay from the village of Kenmore sat Balloch Castle (rebuilt as Taymouth Castle), the seat of John Campbell, 1st Marquess of Breadalbane. The Marquess was chief of the Glenorchy Campbells; a branch descended from Colin Campbell, the younger son of Duncan Campbell, the 1st Lord Campbell of Argyll. Pete's father, John, was passionate about his heritage. In his obituary, his friends wote, "His pride in the ancient and chivalrous clan often found vent in his prime in glowing rehearsals of deeds of prowess enacted by members of it." About 1817 or 1818, a man named John Robertson approached farmers around Loch Tay to emigrate to Canada. If the farmers could pay for their own passage to Montreal, the Government in Canada would grant them land west of the Ottawa River and assist them with transportation to their homestead. Duncan, Catharine and their children John, Elizabeth, and Jannet accepted the offer and made their way to the port of Greenock, west of Glasgow. On July 21st, 1818, the family boarded the 260-ton brig Curlew with over 200 other settlers also bound for the Canadian wilderness. United Empire Loyalists initially settled the heavily forested Lanark County shortly after the American Revolution, but the soil was rocky, and development had been slow. In 1816, surveyors mapped a region that alternated between dense forest and swamp and named it Beckwith Township, after the Quartermaster General of Canada. Many Americans had been venturing north to settle in Canada West, so the government was anxious for more British subjects to migrate. Several societies established themselves to that aim, raising funds to transport Scots, Irish, and English farmers across the Atlantic. However, John Robertson's settlers paid their own passage. The first of John Robertson's recruits arrived on May 19th, after a crossing of only 36 days. However, only 18 settlers arrived on this brig, and they may not have made significant progress in settling Beckwith. On September 8th, the Sophia arrived with 160 settlers, and on September 9th, the Curlew dropped anchor after a 50-day passage. The families made their way up the Ottawa River on barges, debarking at Point Nepean. After the men cut a trail into the new township, the families gathered their belongings and moved in to establish their new homes. Duncan Campbell was among the first to stake his claim to the northeast quarter of lot 11 in concession 4. Those early days were harrowing for the Scots. Another settler, Jessie Buchanan, the daughter of the new Gaelic-speaking Presbyterian minister, described the scene in 1822, "Millions of mosquitos and black flies added to our discomfort... No one dared venture far at night, for wolves prowled around the house in darkness, uttering most dismal howls." Duncan and Catharine had to clear forest to build a home for their family. Buchanan described, "Split logs furnished the materials for benches, tables, floors, and roofs... homes were shanties, chinked between the logs with wood and mud, often without a window, cold in winter, stifling in summer, uninviting always." However, with no way to extract the stumps, they planted their crops around them, using a "cumbrous plough, hard to pull and harder to guide." In the autumn, the family harvested from daylight until dark, with sickle and scythe. Buchanan described the work of women at this time, "Besides attending to the children and household affairs, all spring and summer they worked in the fields early and late, burning brush, logging, planting and reaping. Much of the cooking, washing, and mending was done before dawn or after dark, while the men slept peacefully... When obliged to help out-doors, young mothers took their babies with them - babies were by no means scarce in Beckwith - to the fields and laid them in sap-troughs, while they worked near by. The larger children would hoe, pile brush, pick stones, rake hay, drop potatoes, and be utilized in various ways." Pete's mother, Elizabeth McNaughton, was born about 1815 in Scotland, and she may have belonged to one of the McNaughton families who settled near the Campbells. Duncan McNaughton had arrived on the brig Fame in 1816, with two daughters under the age of twelve, settling in Beckwith, and he may have been her father. However, she may have also belonged to one of the related McNaughton families who settled in neighboring Drummond County. Regardless, she likely grew up facing the same hardship and deprivations as her future husband. Elizabeth and John Campbell married on September 30, 1842. They obtained a farm near Duncan and Catharine and soon had their first child, Catherine Campbell, in 1843, followed by Margaret, Duncan, Peter, Donald, James, John, and Elizabeth Ann. Living on the family farm with his parents and seven siblings, Pete was eager to strike out on his own. As Arnold Davis described, "In 1878 the call of the great untamed North West called him. The North West Mounted Police (NWMP) had been formed in 1873 to provide law and order for the wild west. In 1876 the famous Treaty #6 had been signed between the Cree tribes and some Sioux tribes and the Government." Glowing newspaper stories possibly sparked this call. On February 2nd, 1876, the Manitoba Free Press reported North Saskatchewan River had “the richest land, dotted with lakes and groves. Some miles above the junction of the rivers is situated the mission of Prince Albert and for sixty miles along the banks of the north branch, westward, a very thriving settlement of Scotch and English Half-breeds, numbering in all about 1,000 souls, are situated. These settlers carry on agriculture to a considerable extent, limited, however, by the want of facilities, such as mills, threshers, etc. for the preparation of grain for market.” However, Pete could not have believed that everything was peaceful in the territories. On October 15th, 1877, the Ottawa Citizen reported: “A movement is on foot among the half-breed hunters of the south branch of the Saskatchewan, Prince Albert Settlement, Fort Pitt, and Battleford, to send a delegate to Ottawa to protest against the Northwest Territory being governed by a council which does not include or represent the people of the country… The impression prevails among the French half breeds on the Saskatchewan that that portion of the country was not duly ceded to Canada by the Hudson Bay Company, but only Manitoba.” The West was open to settlement, but the complex and shifting politics of that large territory was anything but resolved. The Hudson Bay Company and the Old WestIndigenous nations had long thrived throughout the plains and woodlands northwest of the Great Lakes. These were fluid and adaptive societies, skilled in international relations, with complex systems of trade. Decades earlier, the horse had revolutionized indigenous cultures and economies and dramatically expanded the buffalo hunt range, which ignited wars with rival nations. And although European buyers lay thousands of kilometers to the east, trade networks snaked across the continent, transporting beaver pelts and buffalo hides east with manufactured goods and technology returning west. The dominant European institution in the northwest had been the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). For two centuries, HBC had owned a British commercial monopoly on the fur trade in North America. The boundaries of this monopoly were anywhere there was a water route to Hudson's Bay; a vast territory named Rupert's Land after Prince Rupert, HBC's first governor. HBC did not claim to own this land; it only held a commercial monopoly from the British Crown on the fur trade. The Government of Great Britain made it clear in the Royal Proclamation of 1764 that the indigenous peoples had never ceded their territory: "And whereas it is just and reasonable, and essential to our Interest, and the Security of our Colonies, that the several Nations or Tribes of Indians with whom We are connected, and who live under our Protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories as, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds... Those nations and tribes allowed HBC to build trade forts throughout the West, and willingly traded beaver pelts and pemmican, bags of dried bison or elk meat mixed with melted fat and sometimes dried fruit. The fur traders were predominately Roman Catholic and French Canadian, although there were also many Protestant English, Scottish, and Irish in the mix. Many of these traders married native women and had children, which the British referred to as half-breeds and the French called Métis, which translated as a person of mixed race. Over the generations, the both the French and Anglo Métis became not merely the children of their parent's cultures, but of the fur trade and buffalo hunt, and they developed distinct languages and cultures. Facing aggressive American expansion, Britain and Canada feared that if they did not quickly settle the West then the United States might annex it. In 1869, Britain persuaded HBC to surrender it's monopoly back to the British Crown. so it could grant it to the new Dominion of Canada. "It is hereby Ordered and declared by Her Majesty, by and with the advice of the Privy Council, in pursuance and exercise of the powers vested in Her Majesty by the said Acts of Parliament, that from and after the fifteenth day of July, one thousand eight hundred and seventy, the said North-Western Territory shall be admitted into and become part of the Dominion of Canada..." The Act required Canada to negotiate indigenous land claims for settlement purposes, but it was clear that Britain and Canada had annexed the North West Territory. DeparturePete departed for Winnipeg in May 1878. He was joined by Thomas Feely, the husband of his sister, Catharine. Tom, Catharine and their one-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, had already lived out in the Western Extension of Manitoba, in the Turtle Mountain district, so Tom knew the lay of land, at least to Fort Ellice on Manitoba's western border. There wasn't yet a rail line from Ottawa to Winnipeg. For three days, Pete and Tom journeyed by boat and train through Fisher's Landing, Minnesota, to Emerson, Manitoba, then purchased a team and wagon to travel the remaining hundred kilometres to Winnipeg. As they rode from Minnesota into Manitoba, Pete would have seen the undulating forests and well-cultivated fields gradually give way to the flat, treeless, unbroken prairie. At first, he must have feared that the prairie was only endless miles of wild grasses, but he might have been soon surprised to see fields of beautiful blue harebells, red lilies, and white anemones. As their week-long journey progressed down into the valley, the ground became swampy, with ditches on both sides of the trail filled with brackish, dark red water. They had arrived in the Red River Valley. The Red River Colony (Selkirk Settlement)The settlement of the northwest would have been far more challenging without the Red River Colony. Sixty-six years before Pete Campbell arrived, while the British were distracted by the War of 1812 and the Napoleonic Wars, Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, attempted to found a Scottish colony in the Red River Valley, near HBC Fort Garry. This land-grab inevitably sparked widespread conflict between Selkirk, HBC, the North West Company, Métis, indigenous nations, and eventually even drew in the Government of Great Britain. In the end, Britain arrested Selkirk, and the River River Colony continued as a mostly Métis settlement, although with British minorities. Immediately after Britain ceded Rupert's Land to Canada in 1869, the designated Lieutenant Governor of the new territory, William McDougall, sent surveyors to the Red River Colony, who began to map the valley into square townships, sections, and quarter-sections, each of which measured 160 acres. This land survey methodology was significant because it did not reflect current land ownership in the colony, and the present inhabitants were justifiably nervous about the future. The 15,000 mostly Métis inhabitants of the Red River Valley apportioned their land into river lots, starting at the river, twelve chains wide and two miles deep. Louis Riel and the Métis regarded McDougall's survey as a prelude to land confiscation and they firmly resisted the intrusion, evicting the surveyors. Riel and his compatriots then established a provisional government for the colony, which they named Manitoba. After a tense and sometimes deadly stand-off, the Canadian government agreed that the Métis would keep their river lots and that it would recognize Métis land claims throughout the colony. Canada subsequently passed the Manitoba Act in 1870, admitting the new province into Confederation. To encourage the Métis to sign away their land claims, the government issued scrip, notes that each Métis could redeem for deeds to 160 to 240 acres of land or the same in cash. While the scheme worked well and most Métis surrendered their claims, bureaucratic delays resulted in scrip not being issued until 1876. Frustrated and in need, many Métis sold their scrip rights to land speculators, often for far less than it was worth, then left Manitoba entirely to homestead further west. Meanwhile, the Métis leader, Louis Riel, who had ordered the execution of a confrontational anti-Métis agitator during the conflict, fled to the United States. WinnipegThree years after the Red River Resistance, a cluster of buildings near Fort Garry had incorporated as the City of Winnipeg and it now served as the gateway to the new North West Territory. Pete and Tom drove their team into St. Boniface, a small settlement across the Red River from Winnipeg. Thomas Osborne Davis, who would later serve as a member of parliament and senator for Saskatchewan, described his arrival in the town: "I crossed the river on the old cable ferry and went to a little hotel. It was a little old board shack and was on the ground that the Winnipeg Hotel now stands on in Main Street… The old Hudson Bay Fort was there with palisades and store houses, and everything was in its original state. There were cannon and everything else in the fort. The city was just a straggling street of shacks and little board houses. The most pretentious building in the city was the little old Queen's Hotel. There were just a few straggling buildings at the back of the Main Street and all back of it was simply like a swamp." Winnipeg hotels were often full by the end of May, and migrants could stay for a week in immigrant sheds at the Forks, the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. Up to five-hundred settlers crammed into the two sheds, which became a hotbed of scarlet fever and small pox in the summer. A cookhouse sat next door, to keep fire out of the main living quarters, along with unheated bath houses. These buildings had no foundations and often flooded in the summer months. If Pete and Tom had not found room in a hotel or the usually full immigrant sheds, the government set up tents for immigrants at the nearby army barracks. During their stay, Pete and Tom joined up with a new friend, Jack Black Mack, the son of Scottish immigrants, who hailed from Canada East (Quebec). After selling their teams and wagons, each man purchased an ox and cart and a saddle horse. They may have purchased Red River Carts for $10 each from Archibald Speers on Thistle Street in downtown Winnipeg, who advertised regularly in the local newspaper. These carts had two five-foot high wheels and were built entirely from wood and animal hide, which made them easy to repair and light enough to float across rivers. Drawn by horses or oxen, they were the life-blood of the western economy, and had been used by settlers, traders, and transport drivers for decades. After loading up their carts with flour, salted bacon, tea, bison hides, feed oats, and a supply of wood and shaganappi, they set off down the trail from Winnipeg toward Prince Albert. Prince AlbertPrince Albert was only a dozen years old when Pete started west. In 1866, Scottish-born Rev. James Nisbet, along with Scottish-Cree Métis, John McKay and George Flett, set forth from the Red River Colony to found a Presbyterian mission on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River. Their avowed purpose was to convert the Nêhiyaw, Nakota, and Ojibwas to Christianity and to serve as a center of "civilized" education. The British referred to the Nêhiyaw as "Cree" and the Nakota as "Assiniboine," names adopted from French fur traders, who had picked them up from their Ojibwa allies. Nisbet, McKay and Flett chose a site a short boat ride down the North Saskatchewan from Fort Carlton. Not surprisingly, the local Cree were hostile toward the new mission and presciently feared that it would attract settlers to their land. However, after two days of negotiations, the Cree relented when George Flett claimed a right to settle the land, based on his own Cree heritage. Nisbet named the settlement Prince Albert, honouring the late consort of Queen Victoria, and hoping to perhaps curry official favour. Prince Albert quickly turned into an agricultural enterprise. By 1871, a 20 Scots and 146 Scottish Métis farmed and worked around the settlement. By 1874, the settlement grew to 300 inhabitants, and with Treaty 6, it would soon expand even faster. Treaty 6Before settlement of the West could begin, Canada was obliged to resolve the land claims of indigenous peoples, such as the Cree, Assiniboine, and Ojibwa. These nations had never ceded their lands to Britain or Canada, and settlement required their consent. However, they were in an increasingly vulnerable condition; over-hunting and drought had devastated the vast bison herds, their primary source of food, shelter, and clothing. On August 23rd, 1876, Mistawasis (Big Child), Ahtahkakoop (Star Blanket), and Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker) of the Plains Cree, along with chiefs of the Assiniboine, and Ojibwa, signed Treaty 6, which provided land reserves, cash payments, farming equipment, famine relief, and medical assistance. Although only a minor chief at the time, Poundmaker was critical of the treaty, declaring, "This is our land. It isn't a piece of pemmican to be cut off and given in little pieces back to us. It is ours, and we will take what we want." But with their people starving and fearful of the violence they had witnessed in the United States, the other chiefs out-voted Poundmaker, and he acquiesced to the treaty. Two years later, in 1878, Poundmaker led his people onto a reserve 64 km west of Battleford, opening the area to settlement. The chiefs may have held out longer, despite their problems, if the Canadian negotiators had been a little less vague about the terms written into the English-language treaty document. Canada held the view that the treaties extinguished all indigenous title and that the indigenous peoples would effectively become wards of the state. However, the chiefs had not verbally agreed to cede all their land rights or their sovereignty, only to share their territories with the newcomers and permit settlement. They also expected the Canadian government to offer real assistance in times of famine. They would soon realize their mistake. The Long and Muddy RoadPete, Tom, and Jack set out from Winnipeg in late May or early June, along the Old Carlton Trail, likely walking or riding alongside their heavily laden carts. After a day of travel down the trail, which was little more than two deep ruts in the hard prairie soil, they gathered dry wood for a fire and collected water from a nearby slough, after skimming off the algae and bugs from the surface. If the weather was dry, they slept under the cart, otherwise they could have set up their tent. If the carts needed any adjustments or repairs, they could rely on their supply of wood and hides. Thomas Davis, who made the same journey two years later, described his experience: "On the first night we camped near old Sandy Murray's. We had a great time with the wild steers, and it was raining very hard; I rolled up in my blanket and got under the cart. When I woke up in the morning I was lying in six inches of water; that was in September '80. " Pete, Tom, and Jack suffered their fair share of rain and mud over the next six weeks. Davis described similar challenges, "it was a continual case of stick and unload and reload the arts. Sometimes we did not make three miles a day... At one place in the middle of the plain we got stuck. We tried to pull the wagon out but failed. The oxen got mired and we unhitched and unloaded the wagon. We had to take the wagon to pieces. We took the wheels off to get it out of the mud. It took us ten days to get across that plain. It was hard work day and night. Pete Campbell later remarked about the many streams that they needed to ford. Davis described the same challenges, "The country was full of water from one end to the other and the creeks were bank high. On the Pheasant Plains at one place we were a whole day getting over a creek." After weeks of exhausting travel, the trail led Pete, Tom, and Jack to Batoche, a settlement of over 500 Métis that had grown around the trading post of Xavier Letendre dit Batoche, who also operated the ferry across the South Saskatchewan River. Two years later, Davis described the ferry, "The mode of crossing the river in those days was to track (tow) the ferry up. A man got in the boat with a pole, and another man got a long rope and tracked it away up the river; then he would load on three or four carts, push the ferry out, and start with two big oars and row, and so he kept going across. He would keep going down-down-down and would take us a mile down the stream before we landed on the other side. Then you had to track the ferry back again with a rope up stream. The ferry was a scow made of lumber that had been whip sawed at Batoche." Once across the river, the three men would have had a comparatively easy road to Prince Albert. They arrived on July 12, 1878. ArrivalBy 1878, Prince Albert had grown to over 800 inhabitants. Shacks and log houses were strung out along the river. When Pete first arrived, there was a blacksmith, a trading post, a doctor, and several schools and churches, but over the next two years numerous merchants, blacksmiths, lawyers, carpenters, and even watchmakers would set up shop. As a Presbyterian, Pete may have sought out the church and found, as Davis described, "a little log Presbyterian Church. An old man named Cevright was the preacher. He was a sort of circuit rider. He used to ride on a pony going around preaching. The old Presbyterian mission house was on the corner of what is now known as Central Avenue and River Street. It had a palisade around it." With no land to farm yet, Pete sought wages. The main industries in town were farming and logging, which meant non-stop milling, "Away on the hill above Prince Albert was an old wind mill built of rough logs and frame and this was used by the settlers to grind their grain... William Miller and Capt. Moore had a little grist mill which was brought in that year and down at the lower end of the town at what was now known as Prince Albert East..." Later in 1878, Captain Henry Steward Moore and Day Hort Macdowall constructed a grist and lumber mill, which would employee Pete for some time. While not working, Pete scouted the land for a good claim. There had been many angry disputes about land in the last several years. First, settlers had clashed with the Hudson Bay Company about the boundaries of their 3000 acre property around Fort Albert, then they argued with the Cree and Ojibwa over where the reserves would be established, and finally they complained to the Canadian government over the survey system. Many of the setters were Métis, and the Red River Valley was still fresh in their memories. Fortunately, by the time Pete had rode into town, the Canadian government was just completing a survey using the river-lot system, and it opened a Dominion Land Claims Office in Prince Albert that September. Pete eventually found his future home, a 160 acre river lot along the north bank of the South Saskatchewan River, 25 kilometres south-south-east of Prince Albert, next to the Muskody nation. However, he could not yet stake his claim. The new Dominion Land Claims office was not accepting claims, which created even more worry and angst among the settlers. Pete may have not have filed immediately anyway. According to the 1872 Dominion Land Act, a homesteader could register a claim on a quarter-section for $5 but would then need to prove that claim within three years by completing improvements to the land. Pete had one more thing to do before starting the clock on those three years. The McGregorsPete returned to Lanark County in the fall of 1879, with important business on his mind: 21-year-old Emma Jane McGregor, the oldest child of Duncan McGregor and Amelia Forbes. Emma's father, Duncan McGregor, had been born in Perthshire, Scotland, on April 24th, 1828, to Robert McGregor and Elizabeth McGibbon, and baptized the same day at the nearby parish church in Fortingall. Duncan's mother died sometime before his 10th birthday and his father raised both him and his sister, Christian, in the milltown of Daloist on Loch Tummel. Robert worked as an innkeeper and a miller, dependable professions in those timber-rich hills. Duncan mastered the trade of carpentry and worked as a cartwright, building and repairing wagons and carts. Emma's mother, Amelia Forbes, had been born in the village of Blair Athol, Perthshire, on April 16th, 1834, to Charles Forbes and Helen Ferguson. Like Duncan, Amelia also lost her mother at a young age. When Amelia grew older, she had found work as a dressmaker and lived with her widowed father and four sisters in a cottage called Inverchroskie House in the hamlet of Enochdhu. Her father was one of the many gardeners who worked at Dirnanean House, the ancestral home of the Small family. Records of a Forbes family in Moulin stretched back several generations. Likely in the region for work, 27-year-old Duncan courted 20-year-old Amelia , and they married in Moulin on January 16, 1855. With three of her sisters married and her youngest sister now 16 and her father still healthy and employed, Amelia departed with Duncan for a new life in Canada. They settled for a time in the village of Ashton, a hub of industry in Lanark County, home to merchants, blacksmiths, weavers, labourers and at least one new carpenter. After several years in Ashton, Duncan tried his hand at farming, but that didn't last and he took up his trade again in nearby Prospect. Duncan and Amelia were prosperous and their family grew quickly. They had their first child, Emma Jane, in 1858, followed by seven more children: Charles Forbes, Duncan Alexander, Nellie, Robena, Kate, Alexina, and Adele, the youngest, who was born in 1875. Scottish culture in Lanark was devoutly Presbyterian and very literate. Families regularly read their bibles but often had libraries made up of weighty classics, such as “Gibbon’s Roman Empire”, and “D'Aubigne’s History of the Reformation.” Both Peter and Emma would have attended school until 13 or 14. The teachers were no-nonsense disciplinarians, who never hesitated to beat a pupil with a strap or even a horse whip on occasion. The students were drilled in geography, grammar, reading, spelling, and arithmetic. With the McGregors in Prospect and the Campbells near Franktown, future husband and wife, Peter and Emma, lived only 14 kilometers apart from each other. It's not certain how the couple met but given their similar background, culture, and religion, they had many opportunities at church or social events. On April 5, 1880, standing beneath the vaulted ceiling of the Methodist Church in Smiths Falls, Ontario, the grey-haired Reverend George H. Davis married together 29-year-old Peter Campbell and 21-year-old Emma Jane McGregor. Pete and Emma wasted little time in returning to Prince Albert, accompanied this time by Margaret and Will Bell, Pete's sister and brother-in-law. Tom Feeley would not return to Price Albert with Pete; he and Catherine had chosen to remain in Manitoba. While the first part of the trip would be a little easier than the last, the rail line from Fisher's Landing now extended all the way to St. Boniface, they would have the same overland journey from Winnipeg to Prince Albert as last time. Except Margaret Bell was at least four months pregnant and had two children in tow, 4-year-old Ada and 2-year-old Alonzo. Despite the challenges, they completed their journey successfully and all arrived in Prince Albert safely. The Bells rented a farm, while Pete and Emma went to work on their land, building a house and barn and clearing and breaking the soil. Fortunately, their land on the banks of the South Saskatchewan was rich in lumber. Unfortunately, the Dominion Land Office still did not accept claims, so they were effectively squatting, although so was every other settler. Emma was pregnant by June of that year with their first child. Peter and Emma would have three children in the first half of the decade: John Duncan Lorne (b. 1881), Charles Forbes (b. 1882), and Olive Esmeralda (b. 1884). The John Smith ReservePeter and Emma had close indigenous neighbours. The Muskoday Nation was also known as the John Smith Reserve, named after Chief John Smith, or Mist-ti-koo-na-pac, who had signed Treaty 6, and was home to the Muskoday people, which meant "No Trees." The Muskoday were of the Saulteaux nation, one of the Ojibwa peoples. Smith and the Muskoday had journeyed to their new land on the South Saskatchewan River from Manitoba after the Red River Rebellion. They were agricultural, raising cattle and farming grain, and had converted to Anglicanism. Settlers' attitudes towards the indigenous people were complex. They viewed themselves racially, culturally, and religiously superior. However, they were also sadly aware that their presence had devastated the indigenous people and destroyed their nomadic livelihoods. The First Nations could recover from the virulent smallpox, measles and flu that ravaged their people, but a voracious European demand for hides had led to critical overhunting of the buffalo and there were only a few hundred left by the late 1880s. To remedy the problem, the settlers fell back on their colonial belief system and sought to convert the Indians to Christianity and to educate them to become self-sufficient farmers. In 1882, the Prince Albert Times was optimistic about indigenous assimilation, reporting conditions in Battleford, "Six Indian reserves have been located and surveyed in the neighborhood. These are inhabited by the Cree and Stoney Indians, who are cultivating their farms extensively and have made for themselves comfortable homes, through the liberality of the Dominion Government, which assists them largely in every way... Schools have been established on three of the aforesaid reserves under the auspices of the Church Missionary Society of England. The native children exhibit a great aptitude for acquiring knowledge and it is gratifying to see the wonderful progress they have made in the various subjects taught them." The settlers relied heavily on indigenous people for labour, routinely employing young men from the reserve. Farmers needed so much labour that other indigenous groups travelled to the area seeking work, including a large band from Dakota. The SiouxFollowing the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876, the Sioux sought refuge in Canada, setting up lodges around Wood Mountain and on the Standing Buffalo Reserve. Canada extracted a promise from them that they would not continue their hostilities with the United States, but the government refused to provide assistance or food. Facing starvation, many of these Sioux came to Prince Albert, seeking employment. Thomas Davis described his first encounter with the Sioux, "There was a large band of Sioux Indians camping across the river that fall. They had run over from Dakota after the Custer massacre. They had all kinds of things they got in the massacre. They had their children all dressed in blue clothes made out of the soldiers' uniforms and all covered over with brass bugles and ornaments they had taken from the soldiers' caps and helmets. They had all kinds of jewelry, watches, etc., they had taken off the dead soldiers. They used to keep up a pow-wow all night long." The Sioux were peaceful and proved to be good workers but their presence did create some alarm in Prince Albert. In response, the NWMP separated a small detachment from the regional capital at Battleford and stationed them at Prince Albert. Duncan and Emma Come WestIn 1883, Pete travelled back to Manitoba to meet up with Emma's family, who had decided to move to Prince Albert. Duncan and Amelia were now in their 50s, while the boys, Forbes and Duncan, were 23 and 21, and the girls Nellie, Robena, Kate, and Alexina ranged in age from 18 to 13. Their youngest daughter, Adele, who would have been 8, sadly died before the 1891 census, so she may or may not have made the journey west. Pete and the McGregors made the journey to Prince Albert on a buckboard with a wagon for their belongings. The age of the Red River Cart was quickly fading. The McGregors settled in the town of Prince Albert, where Duncan worked as a contractor, constructing many homes and stores. Forbes McGregor worked as a teamster, carrying goods back and forth from Winnipeg, Duncan Jr. would work with his father as a carpenter, while the girls would all study to become teachers. Winter of DiscontentThe Prince Albert settlers were profoundly unhappy for various reasons. Although they had experienced some delay, Pete and Emma had been fortunate. They had settled on their property in July 1880 and successfully filed their land claim with the Dominion Land Office on July 6, 1882. However, the Land Office denied the claims of many of their neighbours to set aside land for the railroads. These settlers could purchase their farms at $2 an acre, but they could not claim it under the Homestead Act, at $10 for 160 acres. Additionally, some old-timers had not improved their land, so the government would not recognize their claims at all. However, the Métis argued that they should be granted land under the same conditions as the Red River Settlement. All the settlers, white and Métis, French and Anglo, firmly supported one another. Beyond neighborly consideration, they had good reason. Banks would not set up in Prince Albert because few of the settlers had any security for loans, as they didn't legally own their farms. It was in everyone's best interests to settle the matter. Tempers became so frayed that settlers held a large meeting in Prince Albert on October 16, 1883, forming a Settler's Union, and presented resolutions to the government. Many in the government supported the settlers, but progress was painfully slow. The situation soon became more strained. Canada had decided that the railroads should run through the southern portion of the territory, through Regina, to stave off American encroachment. Prince Albert had still hoped the railroads would build a northern route, but that didn't appear to be happening soon. Moreover, the government strongly encouraged settlement in the south of the territory while ignoring the north. It even refused to allow Prince Albert to incorporate as a town, despite its large population. On August 27th, 1883, a series of devastating explosions from the Krakatoa volcano threw tremendous amounts of ash 80 kilometres in the air. The effects were worldwide, dropping global temperatures over a degree, creating early September frosts across Canada. Crop failures around Prince Albert bankrupted many farmers, but these failures were far more catastrophic for the First Nations. The buffalo herds had disappeared entirely from Canada, and the government discouraged people from leaving the reserves to fish and hunt. Some raised barley and oats, but without mills they couldn't produce the flour they would need to be self-sufficient. With the frost of 1883, starvation and disease became rampant. However, despite treaty obligations, the government slashed funding rather than increased it. In 1882, after the Liberal opposition complained about the growing expense of feeding the indigenous peoples, the Prime Minister, Sir John A. MacDonald, responded: "When the Indians are starving, they have been helped, but they have been reduced to one-half and one-quarter rations; but when they fall into a state of destitution we cannot allow them to die for want of food. It is true that Indians so long as they are fed will not work. I have reason to believe that the agents as a whole, and I am sure it is the same with the Commissioner, are doing all they can, by refusing food until the Indians are on the verge of starvation, to reduce the expense." The conditions became so desperate during the winter of 1883/84, that the Prince Albert Times railed against government policy on April 25, 1884, "If the white man has by his presence driven away the game which provided the red one's support, he is morally bound, at whatever cost, to provide a substitute and even to take the lower ground of economy, it will prove cheaper in the end to feed the Indians than to provide the necessary force to hold them in check, if once goaded past the limit of patience, of which they have proved already that they posses much more than ourselves." Enter Louis Riel. Partial BibliographyMcGill, Jean, S. A Pioneer History of the County of Lanark, Printed by T.H. Best Printing Company Limited, 1968.

David, Abrams Gary William. Prince Albert, the First Century, 1866-1966. Printed by Modern Press, 1966. Rodwell, Lloyd. "Land Claims in the Prince Albert Settlement", Saskatchewan History, Vol 19, No. 1, Winter 1966, pg. 1. Wilson, Garrett. Frontier Farewell, The 1870s and the End of the Old West, Printed by University of Regina Press, 2007. Russell, R.C. The Carlton Trail, The Broad Highway into the Saskatchewan Country from the Red River Settlement, 1840-1880, Printed by Modern Press, Saskatoon, 1955. Daschuk, James William. Clearing the Plains, Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life, Printed by University of Regina Press, 2013 Comments are closed.

|

Archives

2023 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP 2022 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2021 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2020 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2019 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2018 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2017 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2016 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2015 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC 2014 OCT NOV DEC Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed